A Thanksgiving Day lexicological examination of en 恩 and ren 仁

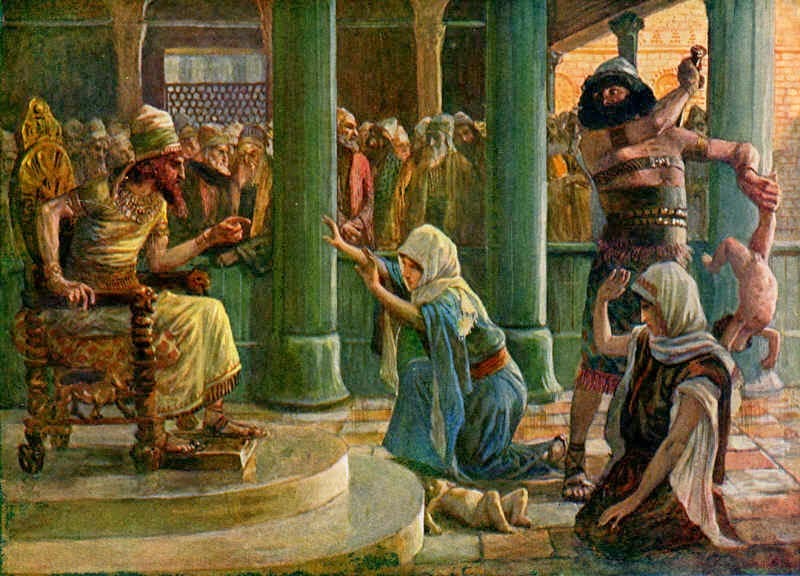

Then the woman whose son was alive said to the king, because her heart yearned for her son, ‘Oh, my lord, give her the living child, and by no means slay it.’ (1 Ki 3:26)

鴟鴞鴟鴞、既取我子、無毀我室。

恩斯勤斯、鬻子之閔斯。

迨天之未陰雨、徹彼桑土、綢繆牖戶。今女下民、或敢侮予。

予手拮据、予所捋荼、予所蓄租、予口卒瘏、曰予未有室家。

予羽譙譙、予尾翛翛、予室翹翹、風雨所漂搖、予維音嘵嘵。O owl, O owl,

You have taken my young ones;—

Do not [also] destroy my nest.

With love and with toil,

I nourished them—I am to be pitied.Before the sky was dark with rain,

I gathered the roots of the mulberry tree,

And bound round and round my window and door.

Now ye people below,

Dare any of you despise my house?With my claws I tore and held.

Through the rushes which I gathered,

And all the materials I collected,

My mouth was all sore;—

I said to myself, ‘I have not yet got my house complete.’My wings are all injured;

My tail is all broken;

My house is in a perilous condition;

It is tossed about in the wind and rain:

I can but cry out with this note of alarm.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Bin 豳風, ‘The Owl’ 鴟鴞

Today is Thanksgiving Day in America. In Chinese, the name of Thanksgiving Day is rendered as Gan’enjie 感恩节: although the translation of gan’en 感恩 works as ‘thanksgiving’ or ‘gratitude’, a bit more literally, it is the holiday where you recognise the kindness that has been done to you. This term kindness, however, gets a bit tricky when it is analysed in a Classical context.

I find it fascinating that only two of the Chinese Classics use this word en 恩, which is connected at the literal heart, pictorially, to the ren 仁 (the much-vaunted virtue of ‘benevolence’ or ‘humankindness’) which was made famous by the Analects of the Ritual School and which is littered ubiquitously across subsequent Confucian commentaries. In the Book of Odes, I have shown you the only occasion in which this word en 恩 is used: for a mother bird who has lost all of her chicks and is in danger of losing her nest. In the Book of Rites, the word en 恩 is used only in descriptions of mourning rituals (Liji 25.7-8; Liji 49.3-5,9). The classical Chinese understanding of ‘kindness’, therefore, is entirely wrapped up in the consciousness of loss: especially the loss of parents or the loss of children.

The reason that I say that en 恩 and ren 仁 are ‘connected at the literal heart’, is that in their original forms, both lexemes are phono-semantic glyphs which share their semantic element: and that element is xin 心 ‘heart’. En features a xin 心 ‘heart’ which is topped by the image of a man wearing clothing or lying on a mattress (yin 因), which is used to indicate the pronunciation. Take away the mattress (wei 囗) and what you are left with is a man (ren 人) over a heart (xin 心), rendering ren 忎, which is the original form of ren 仁.

Linguistically, here I’m forced to wonder if there isn’t an ancient connexion or common root between the Sinitic and Semitic here, because the reconstructed ancient Sinitic pronunciation of ren 仁, *k-niŋ (see Tibetan snying-re སྙིང་རྗེ ‘compassion, generosity, mercy’), shares a consonantal-phonetic resemblance to the Biblical Hebrew raḥamîm רחמים, from the triliteral root r-ḥ-m ר-ח-ם or ر ح م. However, raḥam, despite having a similar adjectival lexical range to en 恩 (‘compassion, kindness, mercy’) has a different nominal, anatomical referent. It does not point to the heart, but instead to the womb: reḥem רחם (also Syriac raḥmā ܪܚܡܐ ‘uterus’).

Motherhood has always been the hardest vocation. The process of giving birth involves a degree of pain and blood loss that half the human race (the half that happens to include me, the author) cannot begin to imagine, and that the other half only understands when they go through it themselves. Mothers very literally give of their own flesh and blood in order to care for a gestating embryo, and then when they do give birth it is as though their own body is being severed. This is the kindness, the mercy for which every human being who comes into this world alive must give thanks. (For clarification, in the Turkic Kazakh language, they still use a loanword from Arabic—рахмет, from Arabic raḥma رحمة—as the basic word for ‘thank you’!)

For the Semite—the Syriac or the Arab or the Biblical Hebrew—the very concept of com-passion, of suffering with and for someone, connects lexically with this pain: the pain (‘ēṣeb עצב) of a mother in the act of giving birth. The lexical connexion between childbirth and compassion is referenced directly in the Scriptural mašal משל in the First Book of Kings (1 Ki 3:16-28) about the true mother and the false mother who brought a child before Solomon, each one claiming that it was theirs. Solomon had suggested that the child should be sliced in two with a sword and each mother given half; and while the false mother agreed to this, the true mother pled that the child should be given to her rival rather than allowed to die.

A Semite reading the Chinese Classics would therefore think it very appropriate that the sole occurrence of en 恩 in the Odes should be in reference to a mother bird that has lost her chicks. That she should give vent to her anguish by crying out about her children, and lay bare the suffering that she went through on their behalf only to see all her work go to ruin, would make sense to the Semitic hearer. I don’t think it readily makes as much sense to us, and this is a problem.

I was shocked—and am still shocked, to be blunt—about the casual nonchalance and even callousness, with which average Americans can rationalise away the images of grieving mothers holding the bodies (or pieces of bodies) of their children in Gaza or in southern Lebanon, with platitudes about Israel’s ‘right to defend itself’. I wonder if we are, in fact, even living in the same moral universe. I see such images and I feel it in my gut (Isa 63:15). This is something I can’t control, it’s instinctive. In those who would rationalise it away: is this instinct simply not voiced? Is it repressed? Silenced? Drowned out by the philosophical voices in our heads? What is broken in us that we have to rationalise a mother’s loss of her children under a rain of American-made bombs?

On the other hand: I have every respect for the brave kids who sat in the street and blocked the parade in New York today. Those kids understood what ‘thanksgiving’ means! Not in the modern commercial sense, but rather according to its classical and in the Scriptural function… or in the same function that modern-day Kazakhstanis do whenever they say ‘thanks’ for anything. They were truly appealing to the raḥam רחם, to the compassion and mercy, to the maternal or fraternal feeling, of families all across the country. They are doing so specifically on account of the children who have been killed and who continue to be killed; the mothers who have mourned and who continue to mourn. (Of course, American Indians have been doing this since 1970; may the Scriptural God bless them richly!)

So hear and understand, readers. Celebrate Thanksgiving as you do. Far be it from me to say no to a plate of turkey, potatoes and stuffing! And, as you do, be thankful for, and kind to, the people around you. That is something that is commanded of you. But rest assured: it isn’t the parade protesters who are ruining Thanksgiving. It isn’t the kids at the table who bring up Gaza who are ruining it. It isn’t the American Indians who are ruining it. Remember that the Scriptural God has shown you His mercy, and that you are expected to show mercy to others in response.

Remember the Scriptural functions of raḥam רחם today as they make their appeal to you.