In-flight movie review №1: Dounia et la princesse d’Alep

An animated transcontinental trek that is long on charm, but short on political wisdom

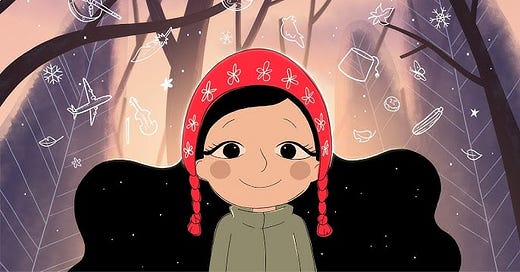

In this little Substack mini-series, I am reviewing three recent (nominally) Middle Eastern films which were available for viewing on my transpacific Delta Airlines flight. The first of these is the French-Québécois film Dounia et la princesse d’Alep (or Dounia & the Princess of Aleppo), which was released in 2022, written by Marya Zarif and directed by Marya Zarif and André Kadi. I found this film a charmingly-quirky and delightful animated story with heart, but one which (an odd charge to make against a 2D traditionally-animated film, I know) lacks a certain depth of perspective.

Dounia is a girl who is born to a woman with hair like a starry dark night, whose name is (fittingly) Layla, and her oud-playing, keffiyeh-wearing, political-dissident lover-turned-husband Nūr. However, after Layla dies of a sudden illness and Nūr is arrested by the Syrian Muḵabarat secret police, Dounia is left to be raised by her grandparents: Jeddo Darwish and Mouné. Darwish is a music-lover who wears an old Ottoman fez which he refuses to take off until the day he dies, while Mouné is a rotund woman who loves to cook—especially compotes and cheeses. When the Syrian Civil War happens, their home is destroyed, and they are forced to leave the country along with several friends. When they meet hardships along the way, they are aided by Dounia’s faith in a handful of beneficently-magical baraka seeds that her grandmother had used while making cheese.

The visual motifs of this film are lush and poignant. The turtle doves, the various forms of flora, the sea and the stars, the moon and the stones—are all excellently animated and woven together to give a feel of magical realism to an intricately-layered scenic backdrop consisting of Aleppo, Izmir, Budapest and several other locations. There are obvious references to Arabic poetry, including the romantic poem Layla wa Majnūn. And the ancient pre-Islāmic history of Aleppo is alluded to multiple times, particularly by a pair of magically-animated statues who accompany Dounia and her family out of the wreckage of her Aleppo home.

And, of course, Dounia herself as well as her family are broadly sympathetic. However, the fact that they are all speaking French accentuates the fact that this animated film takes a viewpoint often aligned with Western European élite-liberal pieties. For example: the Syrian Civil War is portrayed as something essentially akin to a natural disaster with no human cause. Thus, there is no discussion of the sectarian divisions at play in the Syrian rendition of the ‘Arab Spring’. There is no discussion of Israeli interference and land-grabbing. And naturally there is no discussion whatsoever of something so inconvenient as the French colonial violence and exploitation of Syria playing a historical role in the background of the present conflict, as well as the more recent role in the propping up of one side of that war, and damn the consequences for those affected. Adopting a six-year-old’s perspective all but guarantees that we do not question the origins or causes of the civil war. Instead, the sole explanation is that the soldiers are evil and their hearts are ‘shrivelled’.

For another example, like the Syrian soldiers, the North Macedonian and Hungarian police are also shown to behave solely out of callous indifference or spite… except when acted upon by one of Dounia’s baraka seed-induced miracles. All the while, white Western Europeans (and Canadians) are all shown to act purely out of pristine and selfless idealism… as though there is no trace of racism, xenophobia or police overreach to be confronted in either France or Canada. The film falls into the tired and familiar trope of: Western Europe good; Eastern Europe bad. There is, of course, a word for this: propaganda. And rather insufferable propaganda at that.

However, the refugees themselves are treated with the proper human sympathy they are due. Even apolitical people like Darwish and Mouné are forced by circumstances entirely outside of their control, to leave their homes, leave everything they know and love, and make massive gambles on the mere possibility that they might find a place to survive elsewhere in the world. This is made plain in the repeated theme of roots versus flight, which is a common topic of discussion between Lina (a Christian Syrian, friend and fellow-refugee of Dounia and her family) and her sweetheart, the oud-playing Juwān.

Once again, the film is gorgeously-animated and well-written, and it is directed in such a manner that even someone who is not familiar with Levantine Arabic culture will find a great deal to appreciate, enjoy, and learn. Oud music, Levantine cuisine, distant history and mythology all make tasteful and appropriate appearances here. It’s a bit disappointing that the film’s politics are considerably shallower and more naïve than this treatment permits.