The Book of Documents dates back to at least 500 BC. It deals with events that occurred between 2300 BC and 700 BC. It is, to all appearances, the relic of a long-forgotten time. It has nothing to do with our present life. Why, Matt, do you bother to study them? Why are you insisting on the thankless and painstaking task of reading them in the original wenyanwen 文言文—in a Classical language that no one today speaks, and that even Chinese people only study as an elective course?

Indeed, the Documents themselves seem to attest to their own uselessness and futility. The tale of Yao is a rather sorry one. A good ruler surrounded by incompetent people, whose various character flaws and petty squabbling lead to a preventable deluge which kills a large number of innocents, Yao eventually decides to adopt by marriage into his own family the kid of a completely worthless and despicable family—Shun. Shun’s only virtue is that he’s able to get along with all of the horrible people he’s related to. But as it turns out, he rules well… only to be confronted with the same problem at the end of his reign. Shun is left with no choice but to adopt as his son-in-law Yu—the son of the good-for-nothing official who caused the flood in the first place.

Yu comes up with a grand scheme for fixing China. He’s going to make China great again. He makes a plan to build the dikes that prevent more floods. He clears more wastelands further from the rivers into usable farmland. He takes a census of all the towns and villages. He reorganises the whole country into manageable districts. And he institutes a reform of the government that should last forever.

There’s only one problem. His five sons are all (of their own literary admission!) a bunch of screw-ups who don’t listen to him, don’t care about their duties, and only think about themselves. Thus, it’s no surprise when eventually, Yu’s Dynasty of Xia eventually devolves onto a narcissistic failson named Jie who only cares about drinking and holding orgies.

Jie gets overthrown by a righteous prince named Tang of the state of Shang. In addition to instituting political reforms, reorganising the kingdom, revitalising agriculture, pardoning the innocent and punishing the guilty, Prince Tang also takes thought to the future. He hires a tutor for his kids named Yi Yin (who according to tradition was also his cook and confidant), to prevent them from becoming useless failures and screw-ups. But despite his best efforts, Yi Yin is not able to prevail upon Prince Tang’s grandson to uphold a wise or a just course. In the end, the Shang Dynasty is ruled by a drunken, oppressive, oligarchical, sadistic, cannibalistic monster named Dixin. It is left to the Ji family of the province of Zhou to overthrow Dixin.

Ji Fa comes to the throne and institutes an even more ambitious set of reforms than Tang of Shang did. In addition to everything Yu and Tang did, he also institutes an elaborate system of rituals, rectifies the system of weights and measures, creates a theory of government, and outlaws slavery and human sacrifice. And his system lasts under the Zhou Dynasty for nearly 800 years. But by the end, when the Documents are compiled, his kingdom is torn apart by greedy ministers and ambitious warlords.

The Book of Documents is ultimately, on the surface, a cyclical litany of failures. It seems that the more ambitious the project is proposed for fixing the country, the more disastrously it falls. Yet the structure of it is such that the narrative ‘arc’ grows progressively longer with each passing dynasty.

Yu ‘the Great’, founder of the Xia Dynasty, focussed his efforts on meeting human material needs. He provided them with dikes against floods and with more farmland against famine. He organised them into villages and cities to promote production. And the last king in his dynasty, Jie, became a profligate: hoarding his kingdom’s wealth for himself and blowing it on massive drunken bacchanals while his people starved. Prince Tang, the founder of the Shang Dynasty, focussed his efforts on what we would now call transparency in government. In addition to providing for the people, he established oversight for his ministers and instituted punishments for wrongdoing. And in the end, the last king of Prince Tang’s line, Dixin, proved to be an utterly lawless, psychopathic monster. Then Prince Ji Fa, the founder of the Zhou Dynasty, instituted an elaborate system of rituals in order to tame the human beast inside, and make human beings sincerely good. By the end of his dynasty, government positions multiply. So do the numbers and gradations of crimes and fines. And it comes to the point where horseflesh is valued above human life. The rituals which were meant to promote sincerity and ‘humane’ values, in fact produced nothing but hypocrisy and corruption within. The people within are historical, but the Documents form out of their stories a fable. It’s historical fiction with a didactic point.

Unfortunately, the Documents were ultimately historicised: that is to say, they were treated, particularly by the ‘Old Text’ scholars, as an archive of literal speeches and memoranda by literal historical figures. This historicisation was later used to justify a ‘Confucian’ historiosophical theory of dynastic rise, fall and renewal through the Tianming 天命 ‘Mandate of Heaven’ which was expressed in the first sentence of Luo Guanzhong’s novel about the twilight of the Han Dynasty, The Romance of the Three Kingdoms: 話說天下大勢,分久必合,合久必分 ‘It is said that the general trend of the world is that (lands) long divided must unite, and (lands) long united must divide.’ But if this were the only ‘takeaway’ from the Documents, then why would the structure be divided the way it is? Why would the authors spend so little time on Yao and Shun, a bit more time on the Xia Dynasty, more time still on the Shang Dynasty, and dedicate the entire latter half to the troubles of the present dynasty?

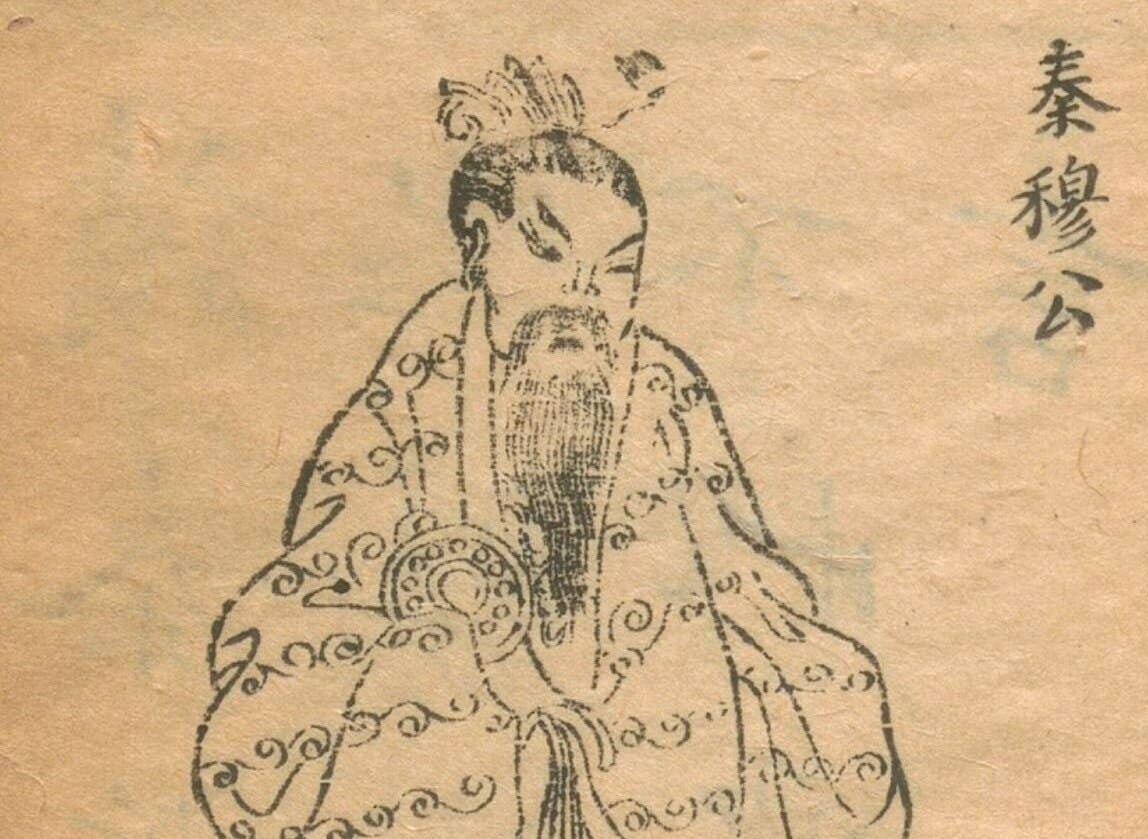

The final word in the Documents is given to Duke Ying Renhao of Qin—who, as it turned out, was the ancestor of Qin Shihuang. He takes the view that the brave warriors and young reformers were full of shit. He’d rather trust the old ministers with ‘yellow hair’, all of whom, unfortunately, he chased off because he wasn’t willing to listen to them. Taken in its bare historical terms, he is referring to the advisors whose advice led to his defeat at the Battle of Yao. But in literary terms, the ‘brave warriors’ he’s referring to are the Marquis of Yin, the Count of the West and the Duke of Bi. The ‘young reformers’ are clearly Great Yu of Xia, Prince Tang and Prince Pan Geng of Shang, and Prince Ji Fa of Zhou. ‘All I want is one minister,’ he essentially says, ‘who is sincere and generous and straightforward.’ But even such a minister is not to be trusted! The Duke of Qin complains that such a minister will ultimately grow jealous and controlling, and become a danger to his country.

The Documents is neither a bare narrative or random collection of historical documents, nor is it a grand unified theory of history. It’s wisdom literature.

The last line of the Documents is:

「邦之杌隉,曰由一人;邦之榮懷,亦尚一人之慶。」

‘The decline and fall of a state may arise from one man. The glory and tranquillity of a state may also arise from the goodness of one man.’

(Book of Documents 《尚書》, Book of Zhou 周書, ‘Speech of the Marquis of Qin’ 秦誓 4)

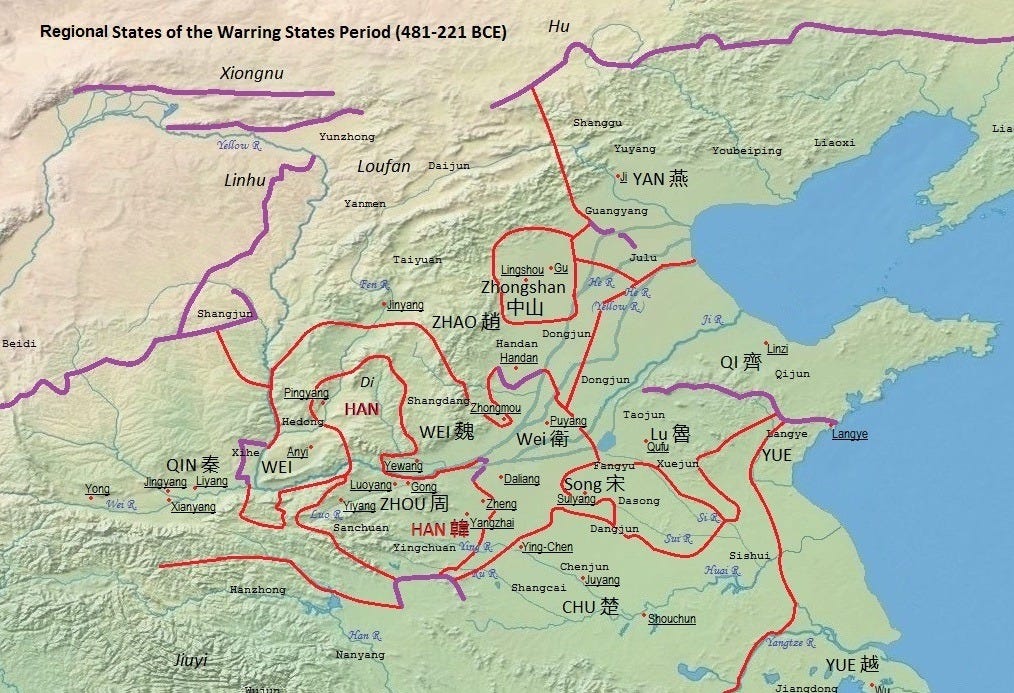

This literary Ying Renhao is addressing the readers of the Documents, the earliest of whom would have been students of the Ritual School during the late Warring States period. We have to hear the text as they would have heard it, in the waning days of a great dynasty, with the last Zhou kings sitting futilely in the capital as puppets or figureheads of the most powerful landowners or nobles whose sole interest was in enriching themselves and running their own states like little extortion rackets. (Speaking as a contemporary American, I don’t think we have to stretch our own imaginations particularly far.)

The Documents do not comprise a call to take up arms or to take up some grand systematic programme of reform… or to sink back into the posture of nihilistic cynicism and resignation. The focus is back on the ‘one man’ at the end of the book, and the repeated insistence throughout the book is Jing zai! 敬哉! ‘Be reverent!’ But Ying Renhao is telling you, in the wake of his own defeat (and in the context of the broader defeat of the Zhou kingdom), not to be reverent to the powerful, or to the ambitious, or even to the wise among men. It is Heaven with its attendant terrors that you ought to revere. And Heaven isn’t capricious or fickle: each dynasty is given ample chances to improve itself. It is the princes and nobles themselves who abandon reverence and give themselves up to their own desires. As the Documents puts it: 天非虐,惟民自速辜 ‘There is not any cruel oppression of Heaven; people themselves accelerate their guilt (and its punishment).’ (Documents, Book of Zhou, ‘Announcement about Drunkenness’ 酒誥 7)

The Documents are in fact a deeply subversive socio-political text. No reform lasts. No family is pure. No dynasty lasts forever. Yet the choice the Duke of Qin voices at the end stands out starkly as a challenge: a bracing antidote to cynicism or resignation.

We are now living in an era of American imperial overreach and exhaustion, and of Chinese ascendancy. Americans would do well to study ancient wisdom literature in a spirit of humility and in the original language. It’s a useful exercise, whether that’s Job, Psalms, Proverbs and Ecclesiastes in the Tanakh, or the Five Classics of the ancient Chinese canon. We would do well to reflect that our standing as a global empire, either since Thomas Jefferson’s ‘empire of liberty’ epistle in 1780 or since the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, has been following the exact same pattern as the empire of Babylon, the empire of Shang or the empire of Rome.

Thus far, the People’s Republic has proven to be a careful, cautious, consistent and programmatic player on the world stage. It has accomplished something truly unprecedented, amazing and praiseworthy: a global middle-class standard of living for most of its people, without the overt conquest, manipulation, expropriation and exploitation of resources from overseas. The People’s Republic has only been involved in two real overseas wars in its 76 years, and both of those took place on its borders and were arguably defensive in nature. Compare that to the incessant warfare America has been making in North Africa, in Eastern Europe, in West Asia and Central Asia, for the last 35 years.

I am often accused of being a ‘China apologist’. I’m sure that others with my views (like Yanis Varoufakis and Serge Glaz’ev) face the same accusations. But that is simply because I do not give any heed to critics in the West who argue from a bad-faith posture. Accuastions of ‘imperialism’ and ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ stem from a classic form of Freudian projection of the West’s own faults onto an external scapegoat. (Who owns most of Africa’s debt? I’ll give you a hint right now, they’re not to the east of the Elbe!)

Yet the kernel of a genuine point lies inside these critiques. Each dynasty begins in the same way. Will it continue the same way that each dynasty before it has? Or can its leaders truly ‘be reverent’ to the needs of its people and the needs of its land and air and water? How can we be sure that even the generally-peaceful, seemingly-friendly, not-immediately-predatory techniques of China’s governing class won’t turn sour? The Documents would tell us that there’s no way we can be sure… unless we’re looking the literary Duke of Qin’s challenge squarely in the eyes.