On Albert Terrien de Lacouperie

He came to the wrong conclusions, but started asking the right questions.

In my lexicographical explorations of the origins of the character tian 天 and of the character shi 師 in particular, I have been broadly suggesting an ancient link, a broad cultural exchange, between the Sinitic and Semitic worlds—between, as it were, the pre-civilisational cores of East Asia and West Asia. I am basing this hypothesis on certain shared trajectories of function, and even shared ancient pronunciations, among lexemes of ancient provenance in both worlds: Tian 天 and ’Elyón עליון, for example; and shi 師 and rab(b) רב. This hypothesis will probably cause me to be associated with another comparative philologist of the Victorian Era, James Legge’s rival Albert Étienne Jean-Baptiste Terrien de Lacouperie, who came up with the hypothesis of Sino-Babylonianism.

First, let me describe where I differ from Lacouperie. Lacouperie’s historiological flights of fancy—even in his own day—tended to be rather far-fetched. James Legge correctly took Lacouperie to task for ignoring key lexicographical resources (such as the Kangxi Emperor’s Dictionary) in his translation of the Book of Changes. I myself think Lacouperie’s core assertion that the Changes is the most ancient text of the Ritual School canon is… well, flat-out wrong. I follow the traditional ordering of the Ritual School canon that holds that the Odes are the most ancient work, followed in order of authorship date by the Documents, Rites[-Music] and Changes, with Spring and Autumn being the most recent. And, of course, though archaeology has exactly zero value in evaluating literature, the archaeological record now definitively shows that Chinese culture has autochthonic origins dating back to the Mesolithic period.

Furthermore, there is a certain chauvinist, racialist logic that underwrites much of Lacouperie’s work, which is deserving of censure. Despite Mesopotamia now being far from considered ‘white’ or ‘Western’, Lacouperie’s notion that Chinese civilization was founded by Aeneas-like adventurers from Mesopotamia carries with it a certain degree of implicit Eurocentrism, and its appeal in Western academe likewise traded on a certain racist currency among his colleagues. It is not, however, unique to him! Most Sinologists of the Victorian Era tended to have a degree of Eurocentric contempt and condescension for their chosen field of study. (Not dissimilar, in point of fact, from the ‘China watcher’ breed of our present day.)

But, to lay all my cards on the table: I do think Lacouperie got done dirty, and his ideas unfairly and too soon dismissed, by his contemporaries in Western academic Sinology. Certain of Lacouperie’s assertions do deserve careful reevaluation.

Lacouperie began his hypothesis with comparisons and noted similarities between Chinese ideograms and Akkadian cuneiform glyphs, as well as the similarity between the Babylonian calendar system (based on units of 60) and the Chinese twelve heavenly branches and ten earthly stems, which likewise created calendrical cycles of 60 units. This is the direction of his study of the Book of Changes. However, lexicographical errors and oversights aside, given that 60 is naturally divisible by 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12 and 15, it is a useful number to work with in all manner of measurement systems requiring fine distinctions or exact division. In both cases, what Lacouperie cites as evidence of cultural borrowing, may simply in fact be a case of convergent cultural evolution. The same applies to his assertions of the architectural similarities between Mesopotamian temples and the raised platforms which house Chinese temples. The Olmec, Maya and Mississippian peoples built raised-earth temples in antiquity, too: it doesn’t follow that they got them from ancient Sumer or Egypt!

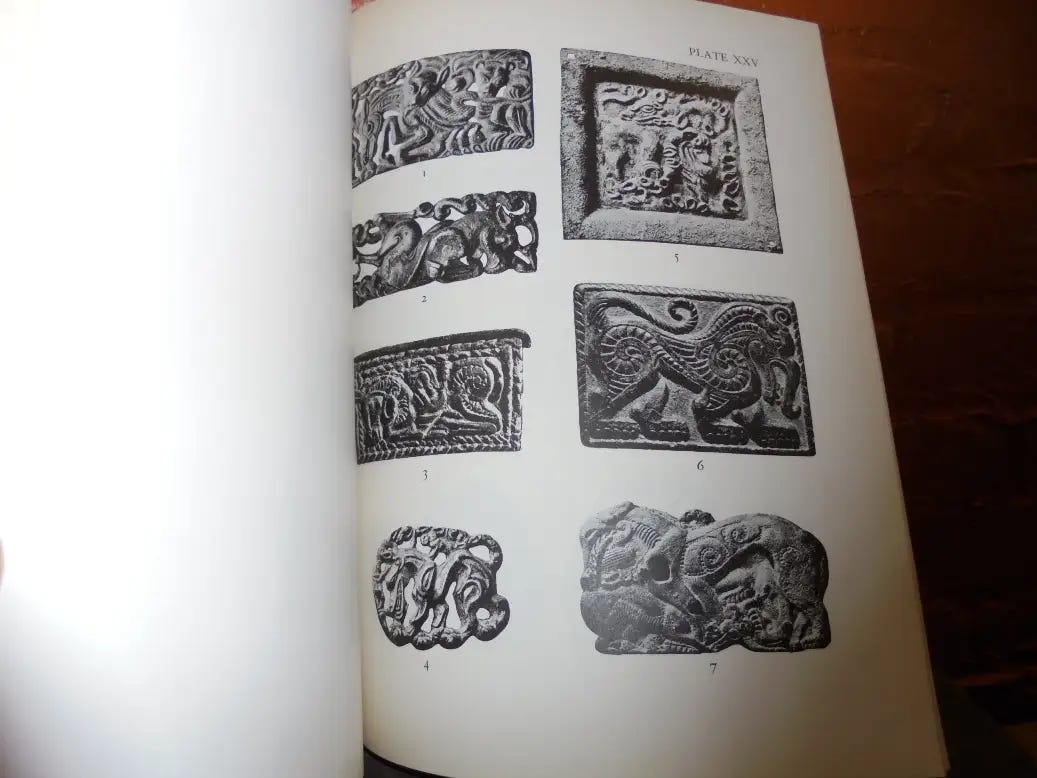

But other of Lacouperie’s ideas do have merit. There is indeed evidence of ancient intellectual and material exchange between West Asia and East Asia, long before the exchanges of the loose web of trade routes coming under the fictive name of the ‘Silk Road’ began. Michael Rostovtzeff, in his classic study of Iranians and Greeks in South Russia written 30 years after Lacouperie’s death, demonstrates quite effectively how, despite a distinct origin of artistic style in the antiquity of the Caucasus and Pontic Steppe region, there was nevertheless a diffusion of discrete artistic motifs, both southward into West Asia and eastward into East Asia. Similar animal motifs appear in classical Mesopotamian art and in classical Chinese art, that took inspiration from a similar set of sources. Is it therefore so hard to imagine a similar diffusion in distant antiquity of linguistic forms, concepts and vocabulary along the same geographical routes?

My aim is much more modest than Lacouperie’s. I do not posit, for example, a Mesopotamian origin of Chinese civilisation. Han Chinese society and culture are very clearly autochthonous and indigenous to their own context, and I have no desire to claim otherwise. Nor do I even insist that strongly upon my posited lexical links between Sinitic and Semitic roots: they are, as I say, hypotheses rather than theories. Rather, I simply ask that Sinologists and Semitologists take each other’s work more seriously, and perhaps engage in the more fruitful work of comparative linguistics. It should therefore be incumbent on both fields to acknowledge that Albert de Lacouperie might not have been as much of a fantasist or a crackpot as has long been believed. Even if his conclusions erred wildly, the lines of inquiry which he followed to arrive at those conclusions may indeed be valid.

Having read U Mass-Amherst professor E Bruce Brooks’s eulogy of Albert de Lacouperie and overview of his intellectual legacy (including his translation of the Book of Changes), I’m in broad agreement with his evaluation:

‘From the early texts, and despite the orthodox interpretations that were attached to many of them, Terrien de Lacouperie gained a sufficiently accurate view of the Spring and Autumn period that he realized, half a century before Chyen Mu and Owen Lattimore, that the “Chinese” territory of that period was in fact honeycombed with non-Sinitic peoples and even states… The whole trend of Lacouperie’s thought still provokes a collective allergic reaction in Sinology and its neighbor sciences; only now are some of the larger questions he raised, and doubtless mishandled, coming to be hesitantly askable.’