The errors of Josephus and Philo

Grammar and lexicography: antidotes to the poisons of archaeology and philosophy

In one blog post I did back when The Heavy Anglophile Orthodox was still active, entitled ‘Always two there are’, I forwarded the claim that the model from which all schisms and doctrinal divergences arise, is modelled after the initial split in the Early Church between Hellenisers and Judaïsers. In various forms, I have continued to hold to that claim, as in ‘Neither Fordham nor Montanica!’. Now, I think I need to revise that claim significantly. Or rather, I need to refine it a bit further.

The split between Hellenisers and Judaïsers in the early Church was a very real one, and it motivated (as I argue in one of my forthcoming books) some of the literary devices that appear in the Gospel of Saint John. But this split masks, or covers over—one can even say it is the personification of—an even more fundamental rift. There is an equal temptation, it seems, to mishandle Scripture in two distinct but related ways, both of which are endemic now in Western culture.

The first of these temptations can be found in its archetype, in the career of the Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus. Josephus, by the way, was a remarkably colourful character. He gained fame first as a commander of local foederati in the province of Judaea loyal to Rome, and then as a Jewish resistance fighter against Roman occupation. But, after a disastrous military defeat at Yodfal, where the Romans slaughtered the entire garrison of the town, Josephus betrayed and murdered the forty men he had taken shelter with, before surrendering himself to the Romans. After this, he switched his loyalty decisively to a series of Roman patrons, including Vespasian, who became Emperor.

Josephus’s seminal work, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία (literally, ‘Archaeology of the Jews’; but rendered in English via Latin as Antiquities of the Jews), is an apologia for the land-claims of the Jewish people as a nation—addressed not to the Jews themselves but instead to the governors and Emperor of Rome. It treats Scripture as though it were solely a factual historical account of a specific bloodline and a specific kingdom. Scripture is therefore taken as a justification of human claims to a particular land, and thus to wealth and to political power.

Another, much later Jewish historian—one not without his own blind spots, but much more honest and honourable than Josephus—once summed up the quintessential problem for historians: ‘Historians are to nationalism what poppy-growers are to heroin addicts: we supply the essential raw material for the market.’ History, as a discipline, consists in the telling of stories. Indeed, our word ‘story’ is a doublet, etymologically linked at the hip, to ‘history’, both being derived from the Greek ἱστορία. History consists of stories written by humans about themselves, whether individually or in groups. And nationalism is rooted in the self-narration of stories about specific groups of people: the work of history is thus an irresistible narcotic which the nationalist can imbibe, the better to distort reality to suit his liking.

The reason that it is a mishandling to historicise Scripture, is because the Tōrah and the Nǝbī’im and the Kǝtubim are, very consciously, not stories about human beings. Human beings are not the protagonists of Scripture: they are the problem. Scripture mocks hero myths. The line of patriarchs must routinely be saved from its own prat-falls by a God Who never shows His true face—not even to Moses! The central narration of the Kǝtubim, is the story of how the human kingdom which the Hebrews demanded of Samuel, fails spectacularly. The Hebrews in the last book are deservedly sent into exile by the kings of Babylon.

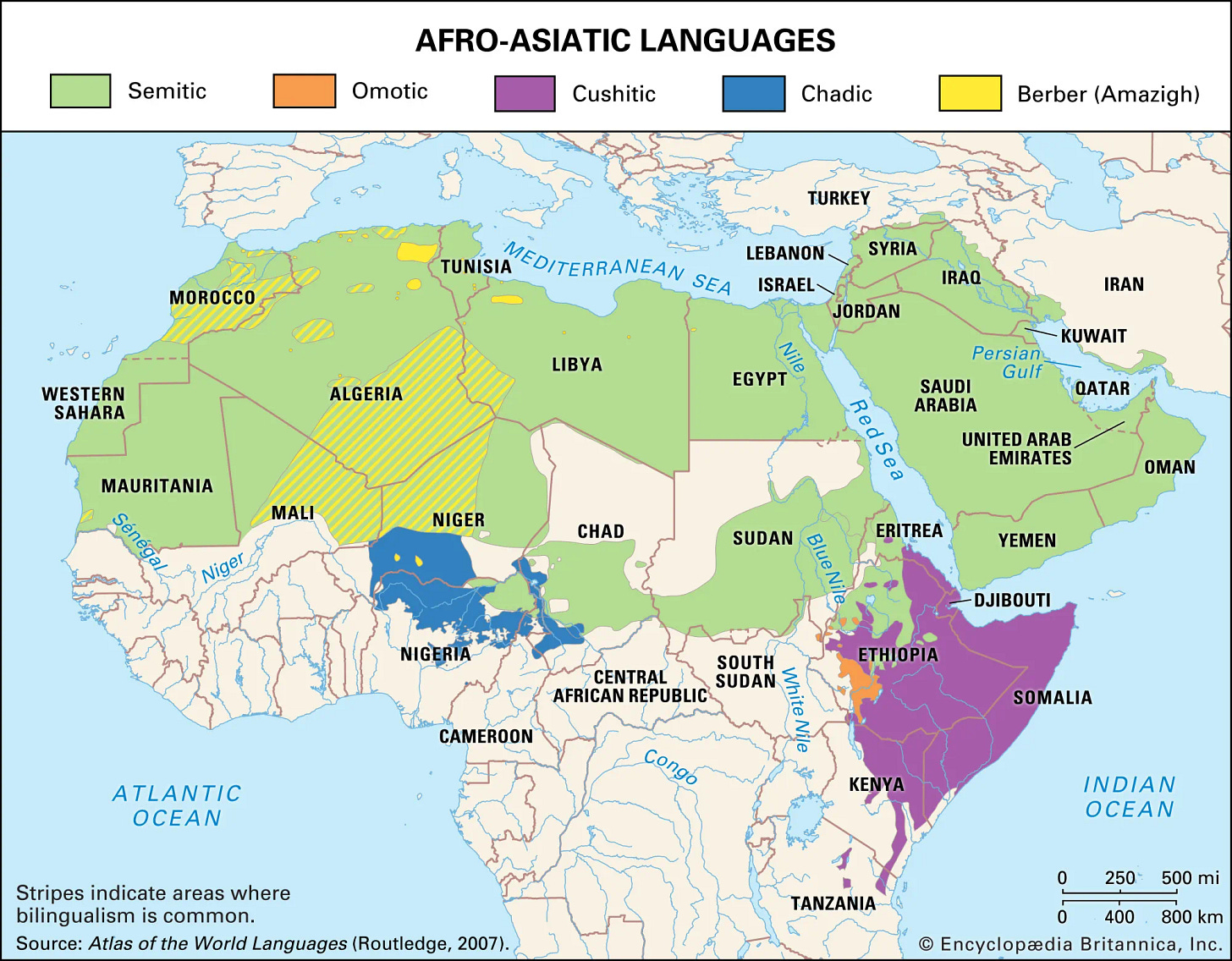

And the last word, the final instruction in Scripture (‘let him go up—’, 2 Chr 36:23, that is, go up to the top of the scroll to read it again), is placed in the mouth, not of a Hebrew nor even of a Semite, but that of an Iranian king—a non-Semite. (And how do we—Westerners in particular—treat the Iranians today? Have we learned nothing from the Kǝtubim?) Scripture is something very close to an anti-history: not a story of human achievement, but instead a litany of inevitable human failure, out of which humans are saved by a God Who is not seen. The attempts to salvage a history out of the narrative of the failures of Israel, become simply laughable when they are compared against the ‘arc’ of the fall of the Hebrew state at the hands of kings who are wise only in their own eyes. The Tanakh is a work of literature. It is not a chronicle, and still less is it a legal title. Its purpose is to instruct, not to flatter, or to entertain, or to present an amicus brief. There is a key qualitative difference.

The second of the temptations to mishandle Scripture can be found archetypically in the career of Josephus’s contemporary, the Hellenic Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria, who was involved in negotiating the relations between the Jews and Greeks of that city. Philo roundly rejected Josephus’s historical interpretation of Scripture, and instead posited that the Tanakh was an esoteric text, meant for the elucidation of mystical truths meant for a select few who were able to understand them… mystical truths which just so happened to be consistent with the prevailing philosophy of Plato’s Academy and of the Stoa of Zeno. (As a Middle Platonist, Philo’s system ended up falling between the Stoic view of moral autonomy and the Platonic-sceptical view.)

Unfortunately, in order to harmonise Scripture with the prevailing contemporary trends in Greek philosophy, Philo was obliged to take the Septuagint as his reference and not the original, consonantal Hebrew text! That is one (though not the only) major flaw in Philo’s scholarship, that led his thought to be broadly ignored and ridiculed for centuries by his Hebrew-speaking Jewish peers. (However, that did not stop him from influencing our scholarship! And one of Philo’s students in Alexandria happened to be… Origen Adamantius.)

The other major flaw in Philo’s approach, much more serious in its consequences, is that it elevates the human reasoning over the text. It imagines a realm above and beyond that of the tôlǝdôt of the heavens and the earth, which is accessible to the human mind, and even then only to the select few human minds that are trained in the proper form of dialectic or discursive reasoning. The Tanakh does the exact opposite of this. Genesis posits the first human beings as the last of the tôlǝdôt of the heavens and the earth (Gen 1:24-27), and also the victims of the discursive reasoning of the serpent in the garden—whose fall was in their seduction by the dream of becoming gods themselves (Gen 3:4-5).

The philosophical approach, rather than submitting to the mašal, instead toys with concepts drawn from Scripture and sets the human brain up over them as their god. When exegetes begin using this approach, anything becomes justifiable. Anything that proceeds out of the human mouth has its root in the human mind, and we know what that ‘anything’ consists of: evil thoughts, murder, adultery, fornication, theft, false witness and slander (Mat 15:15-17). The thing to understand here is that Jesus is not criticising looking at a pretty girl (or boy) the wrong way. He is criticising the mishandling of Scripture through the appeal to human or institutional authority. If you’re listening to the voice in your own head, to the ideas in your own mind, or to the words of some guru or cult leader (no matter how ‘spiritual’!), then by definition you can’t be listening to God.

Articulating a philosophy of Scripture is thus also a perverse mishandling, because it places the locus of control over Scripture in a human idea, a human ideology, a human filter, a human interpretation. This, when the same Scripture thus being interpreted tells us outright that God’s ‘ways are not [our] ways’ and His ‘thoughts are not [our] thoughts’ (Is 55:8)! The Tanakh deliberately, systematically undermines and blows apart any attempts to esotericise it or to vaunt human rationality, even as it sets itself up to instruct the human reason.

And it does this, not through any abstruse or esoteric pattern of symbol and allegory, not through historical object-lessons or Aesop fables, but through its very grammar and Semitic lexicon. It’s a text which cross-references itself in order to show us a mašal: a parable of instruction. This is how the ‘mysteries’ (scare quotes intended) of the Tanakh are readily available to untrained Arabic-speaking laymen and laywomen, in a way that they simply aren’t to philosophically-minded American seminary students, pastors, theology professors, priests and bishops.

My Maghrebi colleague, at the high school where I teach, is a native Arabic (ad-Dārija) speaker and half a generation my elder. She talks about how her peers used to behave when the call to prayer was made, or when the noble Qur’an was recited in their presence. They would fall silent and listen as the text is read aloud. They would not speak. They would certainly not argue. She said, interestingly enough, that they would not even cogitate over what they were hearing: and she said you could tell by looking if they were really listening or if they were formulating some other idea in their mind. She says that this seems to be something which the current generation has lost… though whether or not that is a valid complaint, I have no way to assess because my experience is no reference. Still, it is an interesting observation.

I don’t want to sound like I’m ragging on Jews too hard here, even though I’m clearly calling Josephus and Philo to task for their anthropocentrism. Rabbinical Jews do have the same praiseworthy practice, of listening with respect when the scroll is read aloud to them. It was this impression, and the reluctance to place any level of trust in any merely human authority or institution over-against God, that intrigued me about the work of Rabbi Abraham Heschel, recommended to me on the excellent Lost Prophets podcast by Elias Crim and Pete Davis. Heschel’s interpretations of Scripture are certainly different than mine. And his politics diverge from mine as well. But his basic orientation toward Scripture as coming from a non-human authority, and his unwillingness to place human authority on anything close to the same level, resonated strongly with me. He represents a needed corrective to the errors of both Josephus and Philo, from within the Jewish tradition.

We Christians (and Muslims, to be fair) also need our, doubtless very different, Abraham Heschels. We need someone to snap us out of our personalist delusions, our insistence on man’s equality with God (which in fact only masks a will-to-power to become gods ourselves). We need to hear the kǝtub, not to justify ourselves nor to assert rights where in fact we have none, and not to make our minds look and sound cleverer than they are.

A breath of fresh air.