The lexicography of er 爾 and mi 彌

How a Chinese silk warping-wheel shows us the forgotten multi-functionality of the Messiah

夫子曰:「由,爾責於人,終無已夫?」

Confucius said: ‘You, will you never have done with your finding fault with people?’

The Book of Rites, Tan Gong 1.15

The most basic functionality of the word er 爾 in Classical Chinese is as a second-person pronoun. It means ‘you’. It has several other functions, however, including something or someone close at hand. By extension, and by virtue of Classical Chinese’s highly-flexible grammatical structure, it can also means ‘this’, or ‘thus’, or ‘simply’ (think: classical-to-modern Chinese er yi 而已). In other cases, it simply serves as a ‘filler word’, a neat and tidy final particle which ends a sentence or clause in a pleasing or balanced way.

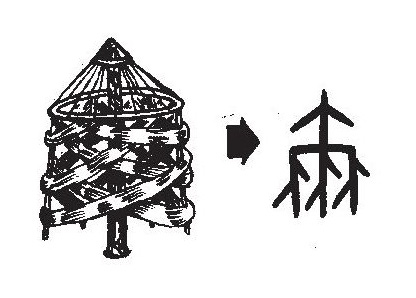

There seem to be two theories of the origin of this character. The first describes the original pictogram from which er 爾 is derived as showing a warp-wheel, a spinning-frame or a loom used for processing silken cloth. This etymology links er 爾 to the modern character mi 𪱾 (also ni 铌), which means ‘warping-wheel’. The second describes it as a kind of weapon—perhaps a spear or something similar, with a sharp head—which has decorative tassels on the end. The latter explanation is bolstered by Chinese etymological dictionaries linking er 爾 in its earliest forms with the character ci 朿 or 刺, meaning ‘thorn’. How the second-person pronoun ‘you’ is derived from either graphic etymology for the ideogram is… at best, unclear. The most intuitive explanation would be its use as something like how an arrow or a pointer-finger emoji is used today, indicating ‘the one I’m pointing at’, though this is entirely speculation on my part and not backed up by any direct lexical evidence.

This character was subjected to one of the earliest organic attempts at character simplification… for reasons which ought to be obvious. Already in the Warring States period (481 BC – 221 BC) one can find examples of the character er 爾 being written on bronze inscriptions as er 尒: a clear precursor of the modern simplified equivalent er 尔.

The word er 爾 actually becomes quite interesting very early on in Chinese Classical studies. It forms part of the name of the earliest extant Chinese lexicography, the Erya 《爾雅》, a name which means, roughly, ‘approaching what is proper’, with the er 爾 in this compound meaning ‘something close at hand’. This book was, in fact, not a dictionary in the modern sense, but in fact a body of lexicographical commentary on the Confucian Classics that delved into the functions of each character where and as it appears in the Classics. The Erya was traditionally ascribed, during the Han Dynasty, to the work of Confucius’s disciple Bu Shang 卜商… who was also credited with establishing the oral tradition that produce the Gongyang Chunqiu Zhuan 《公羊春秋转》, a catechetical work which treated the Spring and Autumn Annals 《春秋》 of Confucius, not as a historical chronology but as a work of prophetic literature.

In post-classical Chinese, the character er 爾, possibly owing to its use in classical literature as a modal particle or a sentence-ending ‘filler word’, came to be used phonetically. That is, it was used for transliterating and approximating the sounds of foreign words and names into Chinese. The hacker handle of the hero of The Matrix transliterated into Mandarin, for example, is Ni-er 尼尔.

The multitude of functions of er 爾 in classical Chinese also precipitated its differentiation into numerous other characters. This was done adding semantic radicals to clarify which function was being expressed. The original function of ‘warp-wheel’, mentioned above, was clarified by adding a ‘wood’ mu 木 radical, resulting in the character mi 𪱾. The function of er 爾 as ‘you’ was clarified during the Tang Dynasty into the character ni 儞 (a ‘person’ ren 人 radical plus ‘you’ er 爾), which was subsequently simplified to ni 你: the modern Chinese word ‘you’.

There is another descendant or sibling character of er 爾: mi 彌, simplified mi 弥, which actually has direct connotations for students of the Hebrew Scriptures. This is because its Tang Dynasty usage by Syriac Christian missionaries directly clarifies the functions of the Semitic triliteral root מ-ש-ח m-s-ḥ!

Mi 彌 contains the ‘bow’ gong 弓 semantic radical, which in fact produces and antonym of er 爾. Er 爾 means something or someone close at hand. But by adding a ‘bow’ radical (bows-and-arrows being a distance weapon!), the character mi 彌 connotes something distant or far away. In classical Chinese, this character was used the same way that the modern Chinese geng 更 is used now, as a comparative adjective modifier. See here:

顏淵喟然歎曰:「仰之彌高,鑽之彌堅。」

Yan Yuan, in admiration of the Master's doctrines, sighed and said, ‘I looked up to them, and they seemed to become more high; I tried to penetrate them, and they seemed to become more firm.’

Analects 9.11

Or, again:

其出彌遠,其知彌少。

The farther that one goes out (from himself), the less he knows.

Daodejing 47

In the passage from Analects, the word mi 彌 modifies ‘high’, making it higher. It modifies ‘firm’, making it firmer. In the Daodejing, it modifies ‘far’ to farther and ‘little’ to less. By itself, mi 彌 means something at its furthest reach or at its fullest point, at its zenith. It therefore can also refer to an expectant mother’s due date, for example—or the full extent of a person’s abilities or willpower. Thus, even in classical Chinese, there is a certain apocalyptic, future-oriented connotation to the term. This may be one reason why, during the late Han and Three Kingdoms periods, the ideogram mi 彌 was borrowed by early Chinese translators of the Buddhist sutras, such as Lokakṣema and Saṅghavarman, to transliterate the Pali names of the future-aligned, millenarian bodhisattvas Amitābha (Emituofo 阿弥陀佛) and Maitreya (Milefo 弥勒佛).

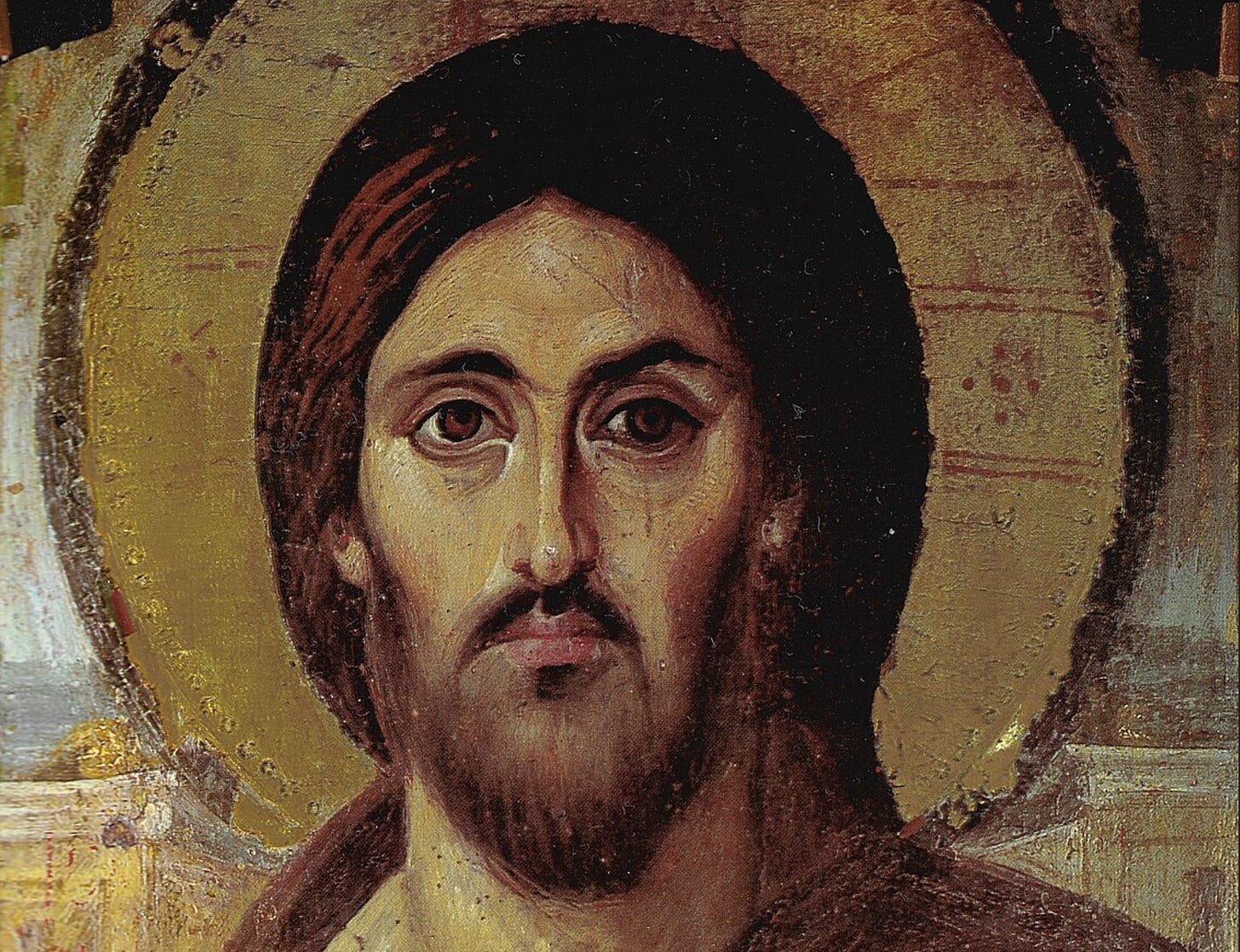

The Aramaic-speaking Syrian Christian monks, led by Aluoben 阿罗本 who visited China during the Tang Dynasty, therefore, were not starting their work on a blank slate. The Christian translators who rendered the Semitic terminology of Scripture into Chinese were operating on the basis of knowledge of the Chinese Classics as well as from the more recent, post-classical work of Buddhist missionaries among the Chinese. They had an interest not only in retaining the sound of these Semitic terms, but also aspects of the function.

Let’s examine the Semitic root m-s-ḥ מ-ש-ח. The basic functions of this root, according to most Hebrew concordances and glossaries, refer to ‘smearing’, or ‘anointing’, or ‘spreading a liquid’ over something. Obviously in context, these glosses would refer to a king, someone whose head had been anointed with myrrh by the high priest. Yet this same root, m-s-ḥ מ-ש-ח, carries with it other functions in other Semitic languages—including Aramaic and Arabic.

In Arabic, for example, the root m-s-ḥ م س ح covers a broad range of functions that don’t necessarily have to do directly with anointing. Of course it carries functions related to anointing as well: masaḥa مسح is the verb ‘to anoint’; and masūḥ مسوح means ‘unguent’. But masaḥa can also mean ‘to survey’, ‘to scan’ or ‘to ascertain the dimensions of’. It can mean ‘to polish’, ‘to scrub’, ‘to smooth over’, ‘to wipe off’ or ‘to blot out’. A ‘surveyor’ is a massāḥ مسّح. A ‘spit-curl’ (of hair) is a masīḥa مسيحة. A ‘feather-duster’ is a mimsaḥ ممسح. And so on. The same highly-variable range of meaning occurs in Aramaic as in Arabic. The same three letters, ܡܫܚ, in Aramaic and Syriac can indeed mean ‘to anoint’. But they can also mean ‘to measure’, ‘to find the dimensions of’, ‘to spread out’ or ‘to wipe out’.

So back to Aluoben. Being faced with the choice of how to render Mǝsīḥa ܡܫܝܚܐ, from the Semitic triliteral ܡܫܚ, into Chinese ideograms, he could have used, for example, the (different) character mi 蜜, meaning ‘honey’. That would have aligned nicely with the function of ‘anointing’ or ‘smearing’, and the valuable status of honey in Tang China would have conferred both the sweetness and the preciousness of the myrrh used in the consecration of a king. But he didn’t. He instead transliterated Mǝsīḥa ܡܫܝܚܐ into Chinese as mi shi he 弥师诃 (or occasionally as mi shi he 弥施诃). This provides us with a much different range (pun intended) of functions!

The usage of this mi 弥 meaning ‘expansive’ or ‘full’, or ‘to the furthest extent’, calls to mind both the functions of ‘to scan / to measure / to find the dimensions of’, and also ‘to polish’ or ‘to scrub’ or even ‘to wipe off’ or ‘to blot out’. It recalls the use of certain related verbs in the Hebrew Scriptures: for example: ‘and the Lord God will wipe away tears from all faces’ ומחה אדני יהוה דמעה מעל כל-פנים w-māḥāh ’Adunāy YHWH dǝme‘â me‘al kāl-fānaīm (Is 25:8)—but also, ‘whoever has sinned against Me, I will blot him out of my book’ mî ’ašer ḥāṭā’-lî ’emǝḥenû missifǝrî מי אשר חטא-לי אמחנו מספרי (Ex 32:33).

The quadruple function of a Messiah as one who comforts, one who edifies, one who corrects and one who obliterates His enemies, is encapsulated in the use of the Chinese character mi 弥 and further cemented in the use of shi 师 ‘teacher’, ‘commander’ (familiar to any fan of kung fu movies in the compound sifu 师父 ‘master’, or to students of Chinese in the modern compound laoshi 老师—yet in its classical and post-classical setting meaning an army commander) and he 诃 ‘to shout (at), to scold, to admonish’. All of these choices on Aluoben’s part make clear that this same verb māḥah, from the same root as the term Messiah, we also invoke every time we pray Psalm 50: ‘according to the greatness of Your compassion, blot out my transgressions’ (Ps 50:1)!

Yet if we are relying on modern Hebrew correspondences alone (even ones as thorough as Strong’s or Brown-Driver-Briggs-Gesenius’s), we would not naturally make this connexion.

It is left to a medieval Syriac monk in China to elucidate it for us.