The lexicography of shi 時

One big difference, and one big similarity, between Sinitic and Semitic outlooks on time

The Chinese character shi 時 (simplified as 时, also seen as the ancient form 旹) is given the common English glosses of ‘hour’ or ‘time’. When used by itself in modern Chinese it means ‘while’ or ‘during’. However, it is also used in numerous modern Chinese phrases and compound words such as de shihou 的时候 ‘when’, shidai 时代 ‘era’, shijian 时间 ‘time’, shishang 时尚 ‘(in) fashion’, sishi 四时 ‘four seasons’ and xiaoshi 小时 ‘hour’. The ideogram shi 時 is very basic workaday vocabulary in modern Chinese, but shi 時 is nonetheless lexicographically a particularly appealing character, since it points to a peculiarity of both classical and modern Chinese grammar… and another cross-functionality with Semitic languages!

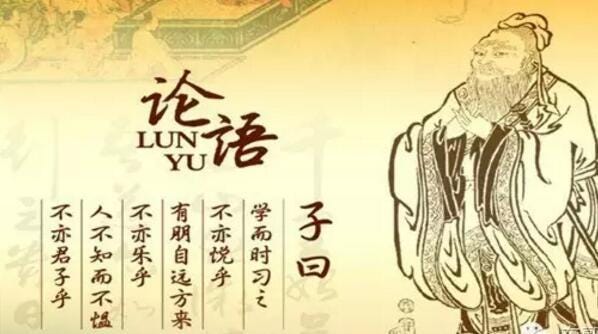

As mentioned above, the character shi 時 began its life on Shang Dynasty oracle bones and turtle shells in the form shi 旹, which is derived from the character zhi 之, an ideogram depicting a foot (zhi 止) with a sandal-lace on it. Originally, this character zhi 之 meant ‘to go’ or ‘to start’. But it also came to represent more broadly the noun, or the subject, that was doing the going. This expanded application gave zhi 之 the multifarious determinative and pronominal functions of ‘this’, ‘that’, ‘he’, ‘she’ and ‘it’, as well as a genitive or possessive marker. This is how in classical Chinese, you can see zhi 之 in different contexts meaning ‘go (to)’ (as in Kongzi zhi Qi 孔子之齐 ‘Confucius goes to Qi’); ‘that’ (as in wu wen zhi 吾闻之 ‘I have heard that’); ‘of’ (Shaodian zhi zi 少典之子 ‘the son of Shaodian’); or ‘it’ (as in xue er shi xi zhi 学而时习之 ‘study and, in time, master it’).

But pay careful attention to this last example, taken from the very first sentence of the Analects of Confucius. The pronoun zhi 之, in conjunction with the sun-radical ri 日, the character shi 旹 came to mean, roughly, ‘that thing that is going on right now’, or ‘the duration that is happening right now’, while the going-on is, well, going on.

Interesting tangential side-note. Around the time of Christ, the Chinese already had several units for keeping track of time. The standard civil unit was the ‘long hour’ or ‘double hour’, which was called shi 時. This was one-twelfth of the day, which was measured from midnight to midnight, with the ordinal hour being measured from 11:00 PM to 1:00 AM. There was another unit, a military unit which confusingly divided the day into ten, called the geng 更 or ‘watch’, which lasted 2 hours and 24 minutes. The civil and military time measures were harmonised by a shared 24-minute unit, the dian 點 or ‘point’: the civil shi lasted 5 dian, while the military geng lasted 6 dian. Making things even more confusing and overlapping, is that there was another military unit of time called the ke 刻 or ‘cut’, which lasted 14 minutes and 24 seconds (1⁄100 of a day).

But the ancient character shi 旹 very directly implies that time is in the active control of the agent, the doer, the person who is going. This is a contrast to the Hebrew term šā‘â שעה ‘moment, period, time, hour’ (cf. Arabic sā‘ah ساعة, ‘hour, o’clock, watch’), which places the control over time into the hands, or rather into the eyes, of an observer.

At first I wondered if there wasn’t some direct connexion, given the similarity of pronunciation between the modern Chinese shi and the Biblical Hebrew šā‘â. But this seems to be not only coincidental but even spurious. (The ancient Sinitic pronunciation of shi was something like the British English pronunciation of ‘dew’. Not much of a connexion to be found there.) The origin and functionality of šā‘â, furthermore, gives rather a different texture to the way in which the classical Semites understood time.

The Semitic triliteral root s-‘-h ש-ע-ה carries with it the meaning of ‘turn’, ‘glance’, ‘look’ or ‘have a look around’. That is, the term šā‘â implies the action of literally turning your head and looking at something in a particular direction, with your eyes. The implication is that what is happening, is what is being beheld. It’s an interesting distinction: time belonging in one instance to the ‘foot’, and in the other instance to the ‘eye’ or the ‘gaze’. It creates a subtle prejudice within Sinitic linguistic horizons toward anthropocentrism, and in Semitic thought toward theocentrism. This prejudice is most pronounced in Classical Arabic, in which as-Sā‘ah الساعة refers in the Qur’an to the ‘last look’: the Final Judgement.

However, there is a feature that the classical Sinitic and Semitic linguistic worlds share, which distinguishes both of them from the main entrants in the Indo-European language family. That is: that they do not use verb tenses. Biblical Hebrew, classical Arabic and modern Chinese all use verb aspect; whereas classical Chinese does not even have aspect, but instead verb voice! (This makes conjugation tables much simpler, no?)

Neither modern nor classical Chinese have verb tenses. There is no past, present or future: all verbs are absolute. If you want to establish when an action occurs, you have to specify the time elsewhere in the sentence: often by using the character shi 時 as a conditional. (For example: Wo kanwang jie shi ta zai lüyou. 我看望姐时他在旅游。 ‘He was travelling while I was visiting my elder sister.’) On the other hand, verb aspect is very important in modern Chinese. In modern Chinese, the perfective aspect is indicated by le 了 or guo 过; if one of these follows the verb, that means the action is complete. (Wo chi 我吃 ‘I am eating’ or ‘I plan to eat’ or ‘I agree to eat’; versus Wo chiguo 我吃过 ‘I have eaten’.) Classical Chinese is even simpler: there are no inflections of tense or aspect for classical Chinese verbs. Instead, classical Chinese verbs are inflected in ascriptive (yidong 意动), transitive (shidong 使动), purposive (weidong 为动) and passive (beidong 被动) voices, and both aspect and tense are either stated elsewhere or inferred from context.

Similarly, the classical Semitic languages—including both Biblical Hebrew and classical Arabic (but not modern Hebrew!)—are also noteworthy for their absence of verb tenses. Like modern Chinese, they use aspect instead. For example: in Arabic, the verb ‘to travel’ has an imperfective aspect, indicating an action-in-progress (‘he travels’: yusāfiru يسافر); and a perfective aspect, indicating a completed action (‘he travelled’: sāfara سافر). Biblical Hebrew and classical Arabic do not entertain any such notion as a future verb tense to go with its perfective and imperfective aspects!

This shared characteristic of Sinitic and Semitic languages actually has considerable ramifications for how they structure their thinking. Sinitic and Semitic languages both deal with what is actually happening or what has actually happened. The foot is moving and the eye is turning to watch it… or else that’s already over and done with. If one wants to imagine a hypothetical parallel universe in which something will already have happened that hasn’t—as Fr Paul Tarazi says, if you want to pretend to have already run a movie of something happening in your head—in order to express such a thought in a Sinitic or a classical Semitic language, one has to navigate some fairly clumsy and obtuse structuring. Whereas in English (as in Greek, as in Latin), ‘will have been eating’ is a grammatically-licit verbal construction that allows for just such a parallel universe inside the speaker’s and hearer’s heads!

Classical Chinese and modern Chinese tend to take a subtly anthropocentric perspective on time whereas classical Semitic ones tend to take a subtly theocentric perspective on time. Even so, both language families are still very firmly tethered to the real world, much more so than we Indo-Europeans, in terms of how they conjugate their verbs and thus speak about time.

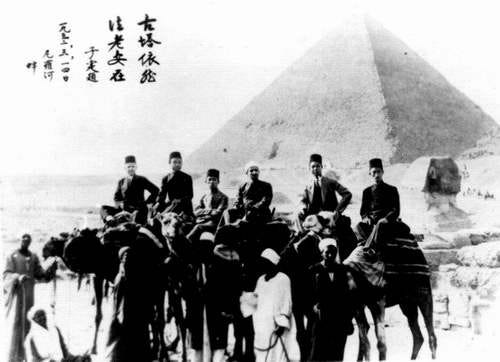

From a historical perspective, it would be interesting to study how this peculiar grammatical similarity, between modern Chinese and Arabic in particular, helped to shape the interactions between the Chinese- and Arabic-speaking worlds during their periods of sustained contact. That is to say: during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 AD) when the Arab Caliphate entered formal relations with the Tang Emperors; during the Yuan Dynasty (1279 – 1368 AD) when Arabs and Chinese were both ruled by the Mongol Khaghanate; and during the modern era (1931 AD – present) after China reestablished diplomatic relations with Egypt and sent Hui Chinese scholars like Wang Jingzhai and Ma Jian to Al-Azhar University in Cairo.

When I was in Changsha recently over the summer, I had a rather long and involved conversation with an observant Hui Chinese fellow from Gansu, who ran a barbeque restaurant across the street from my hotel. He confided that his ‘home’ mosque, which was actually just down the street from our location, was a rather cosmopolitan place. Not only Hui Chinese, but also Uighurs, Turks and foreign visitors (especially those from Arab countries) went there to worship on Fridays. He only knew a few words of Arabic himself (and at that, usually to promote the ḥalāl status of his restaurant’s food), and unfortunately the mosque did not offer Arabic classes, but he did mention that the imam at the mosque had an excellent reader voice.

We talked about various topics, both light and grave. But I remember quite clearly how he spoke about what it was like growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, when (in his words) people had nothing to eat. God be thanked, he said, that his family, including four grandchildren, could grow up in such a time as this one. But—of course—he had no choice in the matter. It wasn’t as though he could up and choose another time to live in. And that seems to be the point. We don’t get to choose our time, or imagine a different one. We have only the present to redeem.