The lexicography of ting 聼...

... and why Jay Chou is important for understanding the Semitic meaning of hearing

The Sinitic ideogram ting 聼 is generally used in modern Chinese, either on its own, or in compounds such as tingjian 听见 or tingdao 听到, all meaning ‘to hear’. It’s also used in words like tingshuo 听说 ‘to hear that’ (very literally, ‘hear-say’) and tingwen 听闻 ‘news received by word of mouth’.

However, this ideogram is also used in the compound tinghua 听话 ‘to obey’: as in Taiwanese pop star Jay Chou’s song 《听妈妈的话》 Ting mama de hua—literally, ‘obey your mother’s words’.

This dual meaning of ‘hear’ and ‘obey’ is attested in the visual construction of the ideogram itself. Note that the ideogram places an ‘ear’ er 耳, over a ‘person carrying a pole’ or a ‘person standing at attention’ ren 壬. It later came to have the connotations of ‘charge’, ‘trust’, ‘duty’ or ‘responsibility’; and this element is today used in the term renwu 任务 meaning ‘task’ or ‘assignment’.

And on the right-hand side, a variant of the word de 德 is used as a phonetic reference.

De 德 is itself a deeply interesting Sinitic ideogram, deeply significant to the ancient Chinese worldview. It’s also one that gets noticeably mangled in English translation, as noted by Sinologists such as Arthur Waley and linguists such as Peter Boodberg.

It is often glossed as ‘virtue’ or ‘ethics’, but these later philosophical shades of meaning which were acquired after its original classical usages, do an incredibly deep injustice to the functionality of the original lexeme.

De 德 is visceral. It is physical.

The main element of this lexeme is zhi 直, meaning ‘straight’. And it is underwritten by a heart, xin 心, which is the seat of life and the core of the animal life-form. The most common form of the word, the one which is seen in standard Chinese, places a chizipang ㄔ on the side, connoting a crossroads, or xing 行.

It is also irrevocably linked in classical sources with the term dao 道.

Sadly, dao 道 is a term which has also been horrendously polluted by dozens of generations of philosophical (neo-Daoist, Buddhist, neo-Confucian, even Christian) idle nattering. So you’ll see entries in every Chinese-English dictionary that gloss it as broadly and as infuriatingly as ‘way’, ‘path’, ‘road’, ‘word’, ‘speech’, ‘method’, ‘principle’ or ‘question’, so that it seems to mean everything and nothing. This term has been so far corrupted that it is often taken to be the equivalent of the Hellenistic logos!

But in ancient Chinese, the term dao 道 was intimately linked to the female sex.

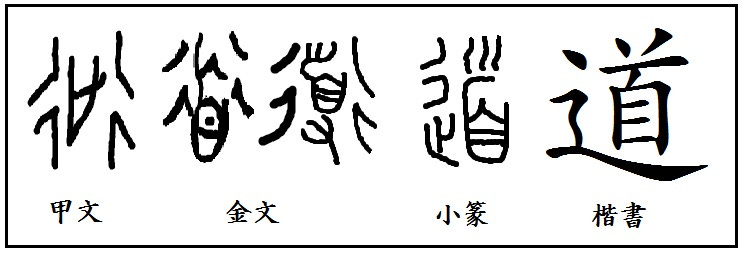

If you look at ancient bronze inscriptions bearing this word, like de 德, dao 道 is a crossroads or xing 行, through which passes a figure with an eye (mu 目) and a right hand (you 又), followed by a stream (chuan 川) of water, or possibly blood. It’s a baby being born, accompanied by the afterbirth.

In its original pre-classical setting, the term dao referred to the birth canal. This connotation is preserved in modern Chinese as chandao 产道 ‘birth canal’.

So de 德, through its linkage with dao 道, refers to the irreversible direction (compare zhi 直, meaning ‘straight’, from which this ideogram comes) that the offspring takes out of the birth canal, or dao 道. Hence, daode 道德, the compound which forms the name of the classical text attributed to Laozi, the Daodejing 道德经.

The point of daode 道德 is a simple one, but it’s almost impossible to render in English without a horrific degree of sesquipedalian clumsiness. All animals are born through a womb. And (Nicodemus happened to be right about this) they can’t go back inside. To have daode is to know that you came from a womb. You have a biological nature and origin that can’t be denied or reversed. You can try to fight it, but ultimately you will only make yourself suffer in the attempt. This is the meaning that a practising Daoist and Chinese student of the classics who hosted me in his home in Fuzhou, Yang Xin Xiansheng, imparted to me.

Getting back to the word ting 聼, though. This word connotes hearing, and also a sense of duty and obedience. But Jay Chou got it 100% right. The word ting 聼 refers especially the obligation of a child to obey its mother, because that child cannot help but derive life from its mother.

But what does all of this have to do with Semitic lexicography?

The Semitic triliteral root s-m-‘ (ש-מ-ע, or س م ع), from which we get the famous Šāma‘ Yiśrā’ēl of Deuteronomy 6:4 (‘Hear, O Israel: the Lord our God is one Lord’), also has this dual meaning of hearing and obedience.

It implies not only the sense of hearing, the physical faculty of the ears, but also the ability to receive instruction. A hearer is in the position of a pupil, a student, someone who perceives what the instructor says, and understands it.

Semitic Hebrew is actually even more insistent than the Greek (akouō—the same verb from which we get the English word ‘acoustics’), that the root s-m-‘ pertains to a learner. The Qal forms of the root s-m-‘ also refer to the physical function of the ear. However, the same form, of the same root, also infers obedience, the relationship of a disciple to a teacher. And here is where the Semitic root gets truly interesting: the root s-m-‘ also refers to the ability of a judge, in a court of law, to hear a case—and finally, to deliver a judgement or pass down an edict.

If you can’t hear, according to the Semitic, you can’t rightly judge.

But the problem is, we English-speakers judge without hearing all the time.

We have a presidential candidate, in fact—a sitting Vice President—who felt confident enough to judge without hearing the Arab-Americans who showed up to her rally in Michigan two weeks ago. When they challenged her on her support for Israel, she accused them of wanting Trump to win, and then told them ‘I’m speaking now’. Remember: if she’s speaking now, she’s not hearing. But she’s judging them and accusing them all the same.

And we ‘nice’, ‘humane’, ‘caring’, ‘liberal’ English-speaking white Americans applaud her for it.

Disgusting. Shame on us.

This is important. If we claim that we are Christians, then we have to acknowledge that our authority, our reference, the One we (supposedly) listen to, was born from a womb in the ‘house of flesh’, Bayt Laḥm, which is now in the occupied Palestinian West Bank. We are obligated to hear the words of the Gospel, which issues inexorably from that source.

The God Whom we worship, Jesus describes as a mother in the travails of childbirth (John 16:21)—right after which He explains his use of the instructional mašal (16:25) to His hearers. So did Paul (Galatians 4:19)—right after which he says, ‘do you not hear the Law’ (4:21)?

Laozi got it. Jay Chou gets it. We don’t.

We have no authority to judge. That’s because we don’t hear, in Scripture, our mother grieving in travail. We don’t hear the Ewe, Rāḥēl, lamenting for her children in the heights (Ramah), who are gone and she refuses to be comforted. And because we don’t hear this, we don’t understand the Law that forbids us from dropping 2,000-pound bombs on defenceless children.