The lexicography of yi 意

If they plan evil against you, if they devise mischief, they will not succeed. (Psa 20:12)

One of the things that I have had to break myself of, in my breaking away from my mental slavery to the continental philosophers, is the use of the word ‘meaning’ or ‘to mean’ in a descriptive sense, let alone a prescriptive one. The functional language theorists, most notably Trubetskoi, are right. And the Jungians and existentialists are clearly charlatans. If Jordan Peterson is the best pupil they can scrounge up today, then what happened to him in the argument with that crowd of twenty atheist kids on YouTube was as predictable as it was pathetic. ‘What do you mean by “believe”?’ Are you kidding me? If your opponent is clearly talking about epistemic assent to a proposition, don’t come back at him with a definition derived from Nietzsche. It doesn’t work. It makes you look disrespectful and dismissive… which is exactly how Peterson came off.

Most people, when they are asked what something ‘means’, they think of examples and anecdotes from their surrounding context and their experience. That’s normal. That’s how we function every day when we talk to each other. People who think they’re a bit more intelligent will perhaps run to get a dictionary and look up the ‘meaning’ of a word. This actually interposes a problem. You’re at the lexicographer’s mercy on the most common denotations of a particular word. If the lexicographer is honest (like Dr. Samuel Johnson), he will provide examples from literature of how that word is used. But most people when they reach for the dictionary simply stop at the numbered denotations.

Prince Nicolas Trubetskoi and his protégé Roman Jakobson had a much more grounded and realistic approach to language than Jordan Peterson (or Nietzsche, or Jung). Trubetskoi and Jakobson examined the usage of particular words in a particular corpus of literature. When the word ‘камень’ is used by Dostoevsky, for example, Trubetskoi says, you need to look at the instances where that word appears and examine it in situ. Maybe there is a particular ‘камень’ in Saint Petersburg that happens to match the lengthy description of the ‘камень’ in Crime and Punishment, fine. But it doesn’t matter. It’s trivia. The ‘камень’ doesn’t correspond to a Jungian archetype or a Platonic form; it has no allegorical value. The question is what Raskol’nikov saw, and how he used it as a hiding place in the text of the novel.

Once you treat words as artefacts of the texts in which they operate, it becomes a hell of a lot easier to discuss them! You can speak intelligibly about the functional semantics without having to resort to abstract ‘meaning’. You can also avoid a lot of the confusion that Peterson provoked in his most recent YouTube debate: one’s ‘belief’ in the existence and use of a pen on the table simply does not have the same lexical value as ‘belief’ in God. Note that this preference of function over meaning is not postmodernism, which is entirely about asserting power over the author! This is very much so a structuralist, formalist approach to the analysis of texts, but it is also respectful of traditional methods of exegesis which attempt to frame author intention within word choice, syntax and grammar.

And here I would say that the ancient Chinese were remarkably wise in their logographical representation of words. At least, this is how Xu Shen interprets it: meaning pertains to the will, and consists in ‘observing the words from the heart’ (意:志也。从心察言而知意也。) Yi 意 is a syssemantograph (huiyi 会意) of a ‘sound’ (yin 音) which is made by your ‘heart’ (xin 心). It’s mental noise! In modern Chinese, yi 意 is used most commonly as ‘thought’ or ‘idea’, but it has expanded functions in compounds like yisi 意思 ‘meaning’; zhuyi 注意 ‘to pay attention, to note’; yuanyi 愿意 ‘to wish’; jieyi 介意 ‘to care about’; and guyi 故意 ‘on purpose, intentional’.

That is shown by its relative rarity in the Classics. When referring to the relation or correspondence of a word or phrase to a thing or situation, the terms wei 為 and wei 謂 are used with much greater frequency. The word yi 意 is used more often for ‘to think, to comprehend’, as here:

無棄爾輔、員于爾輻。

屢顧爾僕、不輸爾載。

終踰絕險、曾是不意。If you do throw away your wheel-aids,

Which give assistance to the spokes;

And if you constantly look after the driver,

You will not overturn your load,

And in the end will get over the most difficult places;

But you have not thought of this.(Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Qi Fu 祈父之什, ‘In the First Month’ 正月 10)

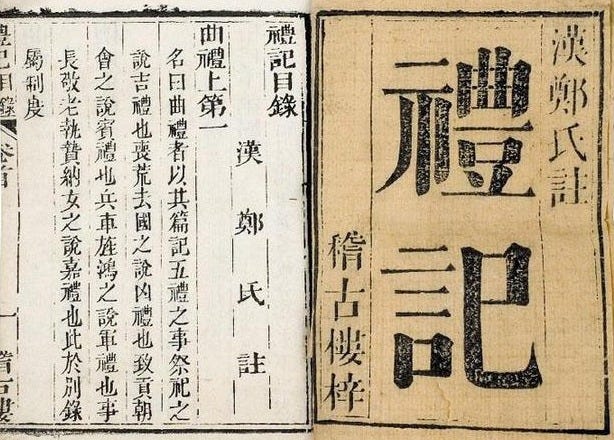

This is the sole appearance of yi 意 in the Odes. The term also appears as ‘to consider’ in the Rites: 意論輕重之序 ‘He must consider the gravity or lightness (of the offence)…’ (Book of Rites 《禮記》 5.47) It also occurs in nominal function as ‘thought’: 故聽其雅、頌之聲,志意得廣焉。 ‘In listening to the singing of the Ya and the Song, the aims and thoughts receive an expansion.’ (Rites 18.49) And also as ‘foresight’ or ‘anticipation’: 孝者:先意承志。 ‘What the superior man calls filial piety requires the anticipation of our parents’ wishes.’ (Rites 24.25) And also, in the Changes, it functions verbally as ‘to feel’ or ‘to be impressed with’: 幹父之蠱,意承考也。 ‘“He deals with the troubles caused by his father:”—he feels that he has entered into the work of his father.’ (Book of Changes 《易經》, ‘Ming Yi’ ䷣明夷 5)

The reference of yi 意 is always internal: it deals, as we might say, with a person’s subjective state. It belongs, as the graphical derivation suggests, to the realm of the xin 心, the ‘heart-mind’. It did not immediately map onto the state-of-affairs in the external world. The Rites caution that for such to occur, the yi 意 ‘thoughts’ have to be made cheng 誠 ‘sincere’:

古之欲明明德於天下者,先治其國;欲治其國者,先齊其家;欲齊其家者,先修其身;欲修其身者,先正其心;欲正其心者,先誠其意;欲誠其意者,先致其知,致知在格物。物格而後知至,知至而後意誠,意誠而後心正,心正而後身修,身修而後家齊,家齊而後國治,國治而後天下平。

The ancients who wished to illustrate illustrious virtue throughout the kingdom, first ordered well their own states. Wishing to order well their states, they first regulated their families. Wishing to regulate their families, they first cultivated their persons. Wishing to cultivate their persons, they first rectified their hearts. Wishing to rectify their hearts, they first sought to be sincere in their thoughts. Wishing to be sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things. Things being investigated, knowledge became complete. Their knowledge being complete, their thoughts were sincere. Their thoughts being sincere, their hearts were then rectified. Their hearts being rectified, their persons were cultivated. Their persons being cultivated, their families were regulated. Their families being regulated, their states were rightly governed. Their states being rightly governed, the whole kingdom was made tranquil and happy.

(Rites 42.2)

Section 42 in the Rites would later be augmented and made part of the altered canon (the Sishu 《四書》 or Four Books) of the Song-Ming rationalist (lixue 理学) turn in neo-Confucian thought, as the Daxue 《大學》 or ‘Great Learning’. The problem is that extracting it from its setting in the Rites allows one to mistake its functional purpose in the original canon, notwithstanding the fact that it contains valuable commentary on the Odes and on the Documents. The ‘Great Learning’ is part of what is in essence an etiquette manual, which serves the literary function of expressing the ideals of Zhou at its height. But in light of the Documents, we should already be aware that these same ideals had already been corrupted and made to serve the interests of the unscrupulous, greedy and power-hungry.

The value of self-cultivation and investigation of things is tied to the original corpus. The Odes are didactically arranged to show the basic proclivities of the human being—the need for food, clothing, shelter, parental affection, conjugal love, honour, stability. They also show how animals such as pigeons and rats are able to provide all these things for themselves and each other simply by following Tian 天. Although their lives are not free of trouble, at least they don’t have kings bossing them around and demanding their blood and sweat and tears, and distracting them from the care of their dear ones. The Documents are arranged in a fashion that undermines the pretensions to righteousness and authority of each new incoming dynasty, and shows how they are vulnerable to corruption and degeneracy from within. The presentation of the Rites as the third book in the canon is meant to showcase a kind of ahistorical Zhou-style utopia: each person in his proper place, behaving appropriately to his parents, his sibs, his wife and children, to his friends and to his superiors. (It was a noble cause. How did it turn out?)

Zhu Xi saw in the ‘Great Learning’ an ideological justification for building a rationalist philosophical system out of bits and pieces of the Rites, along with the Mencius 《孟子》 and the Analects 《論語》, which in the Han Dynasty were not considered canon but rather commentary. That is to say, he does what Peterson does: he lifts passages out of their textual setting in order to extract their ‘meaning’. Yet that system is deeply at odds with the wisdom of the original canon. Zhu Xi, acting in the belief that he is following Mencius, exalts the status of the yi 意, the ‘thoughts’ of the human being, into something that can come to reflect Heavenly principles (Tianli 天理) through meditation and moral cultivation.

The Ritual School which produced the Rites which Zhu Xi is using here, would strongly beg to differ. The author-compilers of the Documents had no illusions about the perfectibility of the human will or the historical endurance of any purely-human system. All sprouts start off bright and green; all human beings start off with the best of intentions; all dynasties start off with vigorous and righteous reforms. But how does it always turn out? Yet there is always the seed of something new and hopeful even in periods of decline and disorder. For every self-important blustering Count of Chong there is a self-critical and chastened Duke Mu of Qin.

I’m not a follower of Jaspers, and I don’t necessarily credit the notion of an Achsenzeit. Wisdom has been available to all times and places, though the people who present it must speak in different ways. But it does seem to me that the literary prophet Isaiah and the author of the Documents had much in common. כּי לא מחשׁבותי מחשׁבותיכם ולא דרכיכם דּרכי נאם יהוה׃ ‘For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, says the Lord.’ (Isa 55:8)

The term maḥšǝbâ מחשבה derives from the Semitic root ḥ-s-b ח-ש-ב ‘to think, to plan, to calculate, to regard, to craft, to devise, to mean’. It’s the same root that furnishes the Arabic word muḥāsib محاسب ‘accountant’. This word is rarely used in Scripture to mean anything good when it’s human beings doing it. People’s thoughts are generally wicked, perverse and contrary. In Genesis alone: Laban ‘calculates’ against his own daughters after they are married to Jacob (Gen 31:15); Judah ‘regards’ his daughter-in-law as a harlot, and uses her as such (38:15); and all of Joseph’s brothers ‘mean’ him harm, though God brought good out of it (50:20). In Exodus, this word is generally used mor complimentarily to refer to the ‘craft’ of a skilled labourer, designing regalia and priestly garb for the Levites (e.g. Exo 35:35); in the books of the Law it is generally more neutral or even positive, being the verb used to ‘impute’ guilt or innocence to the accused, or ‘devise’ fitting sentences against transgressors (e.g. Lev 17:4). But the ‘workers of iniquity’ in the Psalms continually ‘plot’ (20:12) and ‘scheme’ (9:23) and ‘devise evil’ (34:4) against their poor victims.

In Second Samuel, here is how the word is used against David:

ותּאמר האשּׁה ולמּה חשׁבתּה כּזאת על־עם אלהים וּמדּבּר המּלך הדּבר הזּה כּאשׁם לבלתּי השׁיב המּלך את־נדּחו׃

כּי־מות נמוּת וכמּים הנּגּרים ארצה אשׁר לא יאספוּ ולא־ישּׂא אלהים נפשׁ וחשׁב מחשׁבות לבלתּי ידּח ממּנּוּ נדּח׃And the woman said, ‘Why then have you planned such a thing against the people of God? For in giving this decision the king convicts himself, inasmuch as the king does not bring his banished one home again. We must all die, we are like water spilt on the ground, which cannot be gathered up again; but God will not take away the life of him who devises means not to keep his banished one an outcast.’ (2 Sam 14:13-14)

The Hebrew Tanakh—and in fact, the entire Semitic textual tradition—repeatedly humiliates human pride while still leaving the door open for grace. After all, human plans aren’t the only plans!

ان الله كان غلى كل شىء حسيبا

‘Indeed, God is ever, over all things, an Accountant.’ (Qur’ān 4:86)