The lexicography of zun 尊

I will lift up the cup of salvation and call on the name of the Lord. (Psalm 116:13)

I think it is worthwhile to start this essay, actually, by offering a follow-up note on the lexicography of tian 天. I suggested a Classical, possibly pre-Classical link between the Guanzhong Chinese term Tian 天 ‘heaven’, dian 巅 ‘mountain peak’, an unattested (Dené-Yeniseian?) Xiongnu root meaning ‘sky’ and transliterated in Chinese as helian 赫连, and the Semitic ‘Elyón עליון or ‘Illiyyūn عليون ‘Most High’ (which also serves as an epithet for both the Lord, and the heavens).

Assuming the truth of this suggestion (and it is very much so a suggestion—a hypothesis, not a theory), such a transmission would have had to happen well over 3,000 years ago. What is more interesting and relevant, perhaps, is the relationship that the Classical Chinese Tian had with contact with the actual God of the Hebrew Scriptures and His devotees. The first Christians, Muslims and Jews to enter China, all did so during the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907 AD). Christianity, in the form of the Assyrian Apostolic Church, arrived in China with the mission of Bishop Aluoben in 635, and the subsequent approval by Emperor Tang Taizong for a translation of the Christian Scriptures into Chinese. Islām is attested in China from the early 600s: Sa‘d ibn ’abi Waqqas, an Arabic military commander and one of the companions of Muḥammad, supposedly arrived in southeastern China by sea in the 650s during the reign of Emperor Tang Gaozong, and established China’s first Islāmic communities in what are now Fujian and Guangdong Provinces. A Jewish presence in China is first attested about a hundred years later, during the eighth century: probably the result of Radhanite traders settling in Henan Province.

China’s first Muslims preferred to transliterate the name of the One God from Arabic, rendering the sounds of the Arabic name Allāh الله in the Chinese characters An-La 安拉. During the Hui Renaissance of the Hān Kitāb (هان كتاب, 汉克塔布) a thousand years later, Hui Muslim scholar Liu Zhi 刘智 introduced the preferred Chinese Muslim translation of the name of the One God: Zhenzhu 真主 ‘the True Lord’. This was in order to render the name of Allāh intelligible to a Chinese hearer, but also to distinguish the One God from any possibly idolatrous or polytheistic connotations or confusions that might arise from associating Allāh in any way with Tian 天.

This is a similar tack that the near-contemporary Roman Catholic Jesuits of the 16th century took in rendering the name of God into Chinese. Although Matteo Ricci, SJ, acquired a working language of the Chinese Classics, he was also loath to equate the God of Roman Catholicism with the Tian 天 of the ancient Chinese. His preferred rendering was Tianzhu 天主, ‘Heavenly Lord’. This is why Catholicism in China is still referred to as Tianzhujiao 天主教, ‘the Teaching of the Heavenly Lord’. Later English-speaking Protestant missionaries were a tad less scrupulous. There may or may not have been a theological subtext for doing so, but they directly equated the God of the Bible with the name of the wilful and capricious chief god of the Yin Dynasty, Shangdi 上帝, or simply referred to God with the generic Chinese word for a ‘god’ of any kind, Shen 神.

The first Christians in China, however, were Assyrian Christians. They were, like the Arabic traders and military leaders who brought Islām to China through Quanzhou, Fuzhou and Guangzhou, Semites. Although they took a very different approach to the naming of the One God than did the Muslims, they shared with the Muslims a keen desire to avoid confusion. The Name (haŠem השם) was of overwhelming importance, and a hasty ascription of the One Godhead to a concept not lexically-aligned, could prove disastrous to the Chinese hearer of the Text. It is in this light that we should consider Bishop Aluoben’s fateful choice to translate the name of the One God, ’Elohīm, as Tianzun 天尊: ‘Exalted in Heaven’, or ‘Venerable in Heaven’.

Zun 尊, when it is used by itself in modern Chinese, is practically always in the context of mainland Chinese ACG subculture Internet and chatroom slang, as a reaction to something awesome or cool, where it is interfunctional with zan 赞 ‘like’. In more mainstream Mandarin usage, zun is practically always used in compounds like zunjing 尊敬 or zunzhong 尊重 ‘to respect, to esteem’, zizun 自尊 ‘self-respect’, or (especially in historical TV dramas or plays) zunming 遵命 ‘I obey’—basically the Imperial Chinese equivalent of ‘Roger that’.

The character zun 尊 is of ancient and pre-Classical provenance. In its earliest forms, zun 尊 showed two proffering hands (cun 寸, also serving as the phonetic component of the character) holding up an offertory vessel of wine (you 酉, from which we get qiu 酋 ‘chief of a tribe, superintendent of the preparation of liquors’ as well as the modern Mandarin words jiu 酒 ‘wine, alcohol’ and cu 醋 ‘vinegar’), sometimes (particularly in Western Zhou bronze inscriptions) also carrying it up a sacramental terraced mound (fu 阜) for added emphasis. In its original nominal sense, zun referred to the wine-cup or vessel used to honour a superior or a guest. But from its very origins, the verbal character of zun implied ‘to exalt’, ‘to respect’, ‘to revere’, ‘to venerate’, ‘to pay honour to’, and it quickly expanded into its related adjectival and nominal functions: ‘honoured’, ‘venerable’, ‘august’, ‘lord(ship)’.

In this sense, it is equivalent to the Semitic term nāsā’ נשא which can mean to literally ‘lift’ something up with your hands, or else to ‘exalt’ or ‘respect’ or ‘hold in high regard’. In Arabic, the cognate verb našā’a نشأ connotes not only ‘to lift’ but also ‘to raise’, ‘to rear’ or ‘to grow up’, and thus is used in derivative terms like manša’ منشأ ‘homeland’, ‘hometown’, ‘origin’ or ‘source’. An Arabic native speaker would quickly see the connexion to zun 尊 in Chinese Classical referents like the Daodejing:

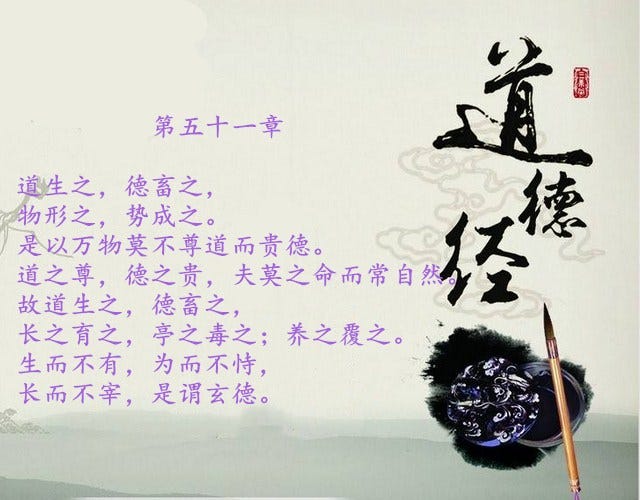

「是以萬物莫不尊道而貴德。」

Therefore all things without exception honour the Dao, and exalt its outflowing operation.

Daodejing 51

「故雖天子,必有尊也,言有父也;必有先也,言有兄也。」

Therefore even the Son of Heaven must have some whom he honours; that is, he has his uncles of his surname.

The Classic of Filial Piety 《孝经》 1.1

The Semitic authors of the Tanakh used the root ’ālef-wāw-lāmed א-ו-ל, ا و ل as the basis for the name of their God: ’Elōhīm אלהים or ’Elāhā ܐܠܗܐ, of which the direct-cognate Qur’ānic Arabic equivalent is Allāh الله. That’s right: lexically, Jews, Christians and Muslims all worship the same God. From the functionalist perspective of language, it should simply not be a point of contention. But once you leave the Semitic linguistic context of Scripture in favour of some extra-Scriptural tradition in one Indo-European language or another, suddenly everything is up for grabs. Theological chest-thumping, ‘unexpected philosophical difficulties’ and insipid liberal ecumenism (which is in fact a linguistic framework for the diplomatic management of a secular empire) are all the bastard offspring of linguistic confusion resulting from leaving the context of Scripture. If you prostitute yourself to masters other than the One God of the Tanakh (as fundamentalists, ‘rationalists’ and ecumenists all inevitably do)… then you may expect ugly unwanted children of unknown parentage.

Though the term refers to a ‘god’ of any sort, the original root connotes ‘might’, ‘power’, ‘strength’ or ‘heroism’. (Compare the Qur’ānic Arabic ’ūlī أولي ‘owners, possessors, men endowed with natural gifts, strongmen, men of military might’.) The Hebrew term is a masculine plural. Fr Paul Tarazi notes in The Rise of Scripture that such a singular reference to a singular god as a ‘They’ was in fact a very common practice West Asian cultures of antiquity, such that it could connote either a god replete with all of that god’s aspects and appearances, or else a God among gods. This is what the Scriptural ’Elōhīm connotes. The epithet ’El ’Elyón אל אליון ‘God Most High’ serves the same function of exalting the Biblical ’El among all other ’elōhīm, which is why it is a commonly-attested name of God in the Hebrew Scriptures.

So in this context—if we understand Bishop Aluoben as attempting to translate ’Elāhā ܐܠܗܐ into Chinese with these connotations in mind—it is tempting to imagine that he picked up the Chinese Classics and attempted a gloss-for-gloss comparison. The Classical-era Erya was, after all, available to Aluoben as a handy tool for translation; as was the Shuowen jiezi of Xu Shen. And we have seen here the lexicographical connotations which Xu Shen derived for both tian 天 and zun 尊. Aluoben would have known and been aware of these.

It is interesting to note that Aluoben, like Liu Zhi and Matteo Ricci after him, chose not to gloss the Name of the One God simply as Tian 天: that is to say, he was aware of the lexical ambiguity that referred to Tian 天 as the supreme God, but also the abode of that God and a complex of gods around Him. Aluoben would have been able to read from Xu Shen that its derivation was related to dian 巅, and (being a Semite and not an idiot) it is easy to imagine Aluoben making the lexical connexion between dian 巅 and ’Elyón עליון.

The appellation Tianzun 天尊, therefore, must have appealed to Aluoben for two reasons. First: knowing the grammatical flexibility of classical Chinese, Tianzun could be taken to mean not only ‘Exalted in Heaven’ but also ‘[the One Whom] Heaven exalts’, thus functionally equating to the Scriptural ’Elōhīm’s role of a ‘God among gods’. Second: a Classical referent for Tianzun already existed in the mind of the Chinese hearer. The Three Pure Ones of the Daoist pantheon all shared the name of Tianzun. One of them I mentioned before: Yuanshi Tianzun 元始天尊; the other two are Lingbao Tianzun 灵宝天尊 and Daode Tianzun 道德天尊. When Aluoben used Tianzun 天尊, a Chinese hearer would know without ambiguity that he was referring to a specific God, and that he was referring to the highest God.

But Aluoben still had to clarify to his Chinese hearers that the One Whom Heaven exalts, Whom he taught of, was not identical to any or all of the Daoist Three Pure Ones. And so he was careful, in describing the Tianzun 天尊 of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, to declare that 「無人得見天尊。」 ‘No human being is given to see the One Whom Heaven exalts’ (cf. Jn 1:18); to rhetorically ask that「何人有威得見天尊?」 ‘Who has the fortitude to gaze upon the One Whom Heaven exalts?’ (cf. Ex 33:20); and to clarify that 「為此天尊顏容似風。」 ‘Thuswise the countenance of the One Whom Heaven exalts is like the wind’ (cf. Jn 3:8).

The reason that he did this is because the Three Pure Ones could be, and often were, depicted in Chinese statuary and iconography (as above). The Tianzun 天尊 of the Hebrew Scriptures is not like the Three Pure Ones. Aluoben’s concern in hedging about Tianzun with the language of invisibility, of incomprehensibility, of likeness to wind… was the same concern as Liu Zhi’s later scruples about not using the concept of Tian 天 to communicate the function of Allāh to Chinese ears.

Both the work of Aluoben in his medieval Chinese translations and commentaries on Semitic Christian texts, and the work of Hān Kitāb scholars like Liu Zhi a thousand years later, are worthy of respect, of being taken up (and read) in this sense. They were not colonisers or ecumenists. That is to say, they weren’t trying to impose their will in a colonialist frame of mind on Chinese hearers and exalt themselves haughtily over Chinese culture. Nor were they trying to diplomatically negotiate and dilute and pollute the target language by appeals to the vagaries of common ideas, in an attempt to expand an empire’s influence.

They were trying, rather, to navigate the lexical framework of scholarly written Chinese while still being true to their own Scriptures and true to their own God. They had naša’ū نشؤوا outside of China, and were yanša’ūna ينشؤون to the Chinese the texts they had brought with them, min manša’ayni من منشأين! Do you see the function? I believe Aluoben did. So did Sa’d ibn ’abi Waqqas. And so did Liu Zhi. Once you lift up the Scripture that has raised you, you are no longer in any position to disrespect or put down the ones you are offering the Scripture to. If you try to do that—like the colonialist missionaries, or (less overt, but more insidious) like the ecumenists—then you are put down under the judgement of Scripture.