The Suzhou Yuanlin 苏州园林 or ‘Classical Gardens’ of that city are a primary tourist attraction of the city for a reason, as well as being worthy of inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage list. Back in 2014, my wife had some business to take care of at her alma mater in the city of Zhenjiang, which is the second in a megalopolis running along the right bank of the Long River from Nanjing in the west to Shanghai in the east. Suzhou being the fifth in that chain before reaching Shanghai, the two of us got to do some sightseeing there.

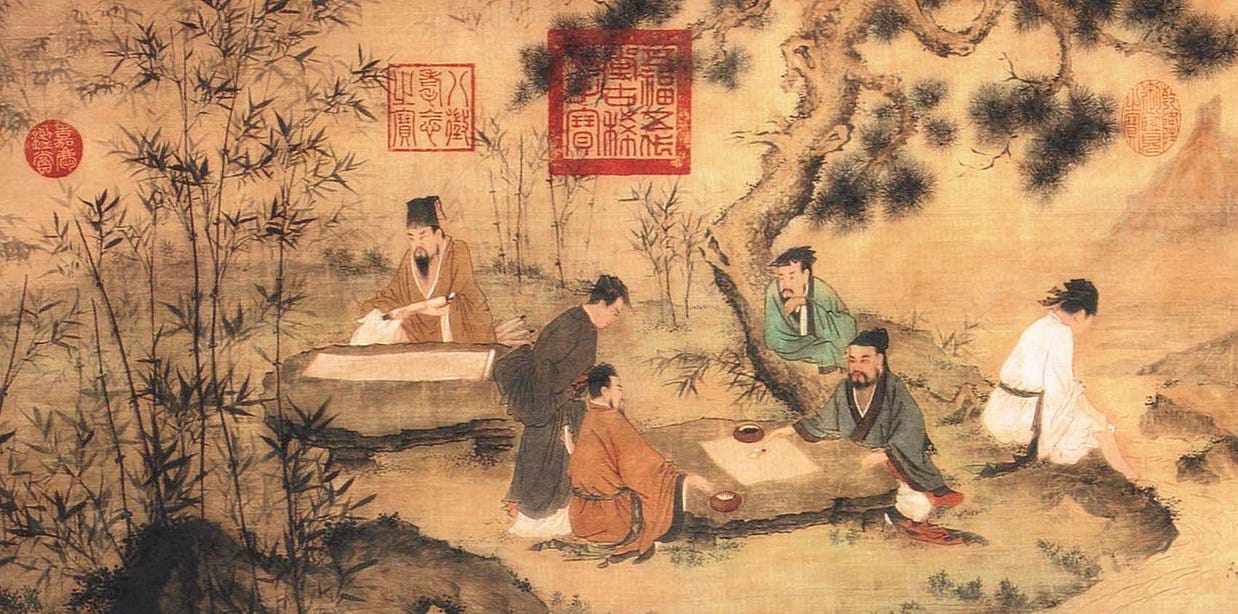

We visited the most famous of the Classical Gardens, the Humble Administrator’s Garden or Zhuozhengyuan 拙政园. If you ever get the chance to visit there yourself, it is highly worth the time and effort. The walled garden is a masterpiece of harmonious cultivation and landscaping. A circuitous path of broad flagstones and cobble mosaic, some of it shaded with covered bamboo walkways, leads one through a labyrinth of ponds interconnected with small rippling brooks, with long elegant stone bridges providing views of a serene landscape of rock outcrops graced with pines and willows and crêpe-myrtles. Dozens—and I do mean literal dozens!—of pavilions are scattered throughout the three walled sections of the garden, some appointed with period-specific Ming Dynasty wood furniture, curios and artwork, and elegantly constructed to provide pleasure to the eyes from within and from without, and not to override the green and living elements of the landscape. The ponds themselves are home to lotuses, carp, and even pairs of yuanyang 鸳鸯 or Mandarin ducks. We were there in December, so the place was relatively quiet, and it was breathtakingly beautiful.

I bring this up to demonstrate how I am using the word ‘space’ in the present essay. When people of my generation and a little older hear the word ‘space’, their mind automatically fills in: ‘the final frontier’. We think of the Apollo missions, the ISS, Star Trek. People a bit younger than me would think of Blue Origin and SpaceX. This isn’t unique to Americans: Chinese people would probably think of the Chinese space missions, hearing this word in English. That isn’t what I’m talking about here. The Humble Administrator’s Garden is finite, it’s human-scaled, it is designed to be suitable both for private enjoyment and for the entertainment of guests. I’m talking about this kind of space the way it is arranged and presented in a Chinese garden, or in a field, or in the room of a house.

The Chinese character which refers to space in this sense is jian閒 (variant 間, simplified 间). By far and away its most common present-day usage is in the compound shijian 时间 ‘time’. By itself or as part of the compounds zhijian 之间 or zhongjian 中间 it can also function as a preposition: ‘between’. It also serves in a number of other common compound words: fangjian 房间 ‘room (of a house or building)’; xishoujian 洗手间 or weishengjian 卫生间 ‘bathroom’; kongjian 空间 ‘space (in the sense I mean here)’; jiandie 间谍 ‘secret agent, spy, mole, rat’; minjian 民间 ‘folk, popular, pertaining to the commons’; and renjian 人间 ‘Midgard, the saeculum, the mortal realm’.

This character, the 135th most-common character in Chinese writing, is classified by Xu Shen as a syssemantograph (huiyi 会意): in its most basic form, it shows a moon (yue 月) shining through the two halves of a gate or door (men 門). The Erya links it to tiao 窕 ‘to penetrate, gap, unfilled space’, and Xu Shen defines it as synonymous with xi 隙 ‘gap, crack, crevice, break’, with which it may once have shared a similar pronunciation. In Old Chinese, the character jian 閒 was likely pronounced /*kreːn/, whereas xi隙 may have been pronounced /*kʰraɡ/. This reconstruction is based on the term’s cognates in Bama, kra: ကြား, and Mizo, kâr, and it most likely indicates an onomatopoeic origin, the rattling or cracking sound made when something hits a gap or comes loose in a space.

This would seem to be indicated by its earliest use in the Classics, where it is precisely onomatopoeia for the rattling of rolling carriage-axles: 間關車之舝兮、思孌季女逝兮。 ‘Jian-guan went the axle ends of my carriage, as I thought of the young beauty, and went [to fetch her].’ (Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Sang Hu桑扈之什, ‘Axle-Ends’ 車舝 1) The second function this lexeme enjoyed was verbal-nominal, ‘to end, to finish, to cut off’ (though here it may be a misprint or erroneous transcription of the similarly-pronounced tian 殄 ‘to cut off, to extirpate, to extinguish’): 天降時喪,有邦間之。 ‘Heaven sent down ruin on him, and the chief of the territory (of Shang) put an end (to the line of Xia).’ (Documents 《尚書》, Book of Zhou 周書, ‘Numerous Regions’ 多方 3) The function of ‘between’, as a preposition, appears to be contemporary with this. 時則勿有間之。 ‘And let us never allow others to come between us and them.’ (Documents, Book of Zhou, ‘Establishment of Government’ 立政 7) And also: 牖間南嚮,敷重篾席,黼純,華玉,仍几。 ‘Between the window (and the door), facing the south, they placed the (three)fold mat of fine bamboo splints, with its striped border of white and black silk, and the usual bench adorned with different-coloured gems.’ (Documents, Book of Zhou, ‘Testamentary Charge’ 顧命 4)

The nominal use of jian 閒 in the function of ‘space’ is attested in the standard commentaries on the Book of Changes, expounding its cosmology. 以言乎天地之間,則備矣。 ‘If we speak of [the Changes] in connexion with all between heaven and earth, it embraces all.’ (Changes 《易經》, ‘The Great Treatise I’ 繫辭上 6) Also: 有天地,然後萬物生焉。盈天地之間者唯萬物,故受之以《屯》。 ‘When there were heaven and earth, then afterwards all things were produced. What fills up (the space) between heaven and earth are (those) all things. Hence (Qian and Kun) are followed by Zhun.’ (Changes 《易經》, ‘Introduction to the Seals’ 序卦 1)

The idea of the renjian 人间 or ‘mortal realm’ being a ‘gap’ or a ‘space between’ heaven and earth has a clear resonance with the cosmology of the West Asian Scriptures. The Babylonian-Assyrian, Persian and Canaanite cultures all conceived of the cosmos as a vaulted dome, a hemisphere situated between the firmaments containing the two waters. This was contrasted by German philosopher Oswald Spengler with the Classical-Apollinian understanding of ‘space’ as concerned with the self-contained form, with complete and bounded perfection: whether that is the chiseller with his block of marble fashioning out of it the perfection particularly of the human body, or the Doric column (or colonnade!) with its enclosed and bounded symmetries, or the social ideal of the polis or city-state community. And he contrasts both with the post-Renaissance penchant for striving outwards, tragically, into infinite space—the Newtonian-Copernican model of the universe, gravity-defying Gothic arches and the unfulfilled tensions of Baroque organ music.

The concept of a ‘gap’ or ‘space’ in Biblical Hebrew, marked by the triliteral r-ḥ-b ר-ח-ב ‘to enlarge, to widen, to open, to expand, room’, is perhaps unsurprisingly linked to territory, a particular area of ground with particular resources. The first appearance of this triliteral in Scripture is when Isaac is at odds with Abimelech over the wells of water he dug in Gerar during the famine:

ויּעתּק משּׁם ויּחפּר בּאר אחרת ולא רבוּ עליה ויּקרא שׁמהּ רחבות ויּאמר כּי־עתּה הרחיב יהוה לנוּ וּפרינוּ בארץ׃

And he removed from thence, and digged another well; and for that they strove not: and he called the name of it Rehoboth; and he said, For now the Lord hath made room for us, and we shall be fruitful in the land. (Gen 26:22)

Also, in the Psalms: תּרחיב צעדי תחתּי ולא מעדוּ קרסלּי ‘Thou hast enlarged my steps under me, that my feet did not slip.’ (Psa 17:37; see also 2 Sam 22:37) Given the martial imagery of what came before—the bow and the shield—the idea in this passage is that God has provided a foothold, a level place on which a combatant can stand without being easily dislodged and flung down. (This is the same sense in which the same root used, adjectivally, in Surah 9 of the Qur’ān.) But this is the prototypical usage: it’s usually a piece of land or a territory which is thus ‘widened’ (see Exo 34:24; Deu 12:20, 19:8), just as the Humble Administrator’s Garden is wide enough to roam around in, to breathe, to sit, to relax, to be refreshed, to entertain guests. Obviously there are secondary functions as well. One has to ‘widen’ one’s mouth to be able to speak (Psa 34:21, 1 Sam 2:1) or to eat (Psa 80:11).

The other figurative usage of rāḥab, not a positive one, is the ‘enlargement’ of the heart through grief or worry. צרות לבבי הרחיבוּ ממּצוּקותי הוציאני ‘The troubles of my heart are enlarged: O bring thou me out of my distresses.’ (Psa 24:17) The grave can also be enlarged in the same fashion as a mouth, swallowing up every man together with his worldly treasures and renown (Isa 5:14).

But the idea is that the physical space is widened to make room for something, whether that is a foothold whereon a warrior can fight, or a place to dig a well for water, or a mouth that can make room for speech (good or bad) or food. In Arabic, this same root r-ḥ-b ر ح ب is used in the standard phrase for ‘welcome’, marḥaban مرحبا, the literal gist of which is ‘we have space’ for a guest! (The same functionality, but with different roots, is seen in the greeting ahlan w-sahlan اهلا وساهلا, which is the phrase for ‘hello’, but which can mean ‘we have people, we have room’.)

Even in this handful of examples, we can see in the term rāḥab רחב a kind of reciprocity at work. מתּן אדם ירחיב לו ולפני גדלים ינחנּוּ ‘A man’s gift makes room for him, and brings before him great men.’ (Prov 18:16) This reciprocity is seen in Deuteronomy most effectively. God makes room for the sons of Jacob in the land of Canaan; He enlarges their borders and their coastlines. But in return, He expects them to exercise hospitality and welcome, after the Arabic function of the same word! The promise to enlarge the borders of Jacob’s children in Deuteronomy 12 is tethered to their hospitality toward the Levites; and in Deuteronomy 19 it is tethered to the command not to shed innocent blood and to give shelter to the fugitive whose guilt has not been proven!

And the same reciprocity works the other way, too. Isaiah’s threat of death and hell engorging themselves upon the Israelites and their treasures in chapter 5 is preceded by a warning against imbibing fine wine, engorging oneself upon rich foods, and indulging in music and luxuries, while ‘honourable men are famished, and their multitude are dried up with thirst’ (Isa 5:11-13). Inhospitality, hardheartedness and greed lead to death and hell, almost as a rule of nature. Yet if the law of hospitality is followed, and the ‘children of the desolate’ are fed and housed and cared for:

הרחיבי מקום אהלך ויריעות משׁכּנותיך יטּוּ אל־תּחשׂכי האריכי מיתריך ויתדתיך חזּקי׃

כּי־ימין וּשׂמאול תּפרצי וזרעך גּוים יירשׁ וערים נשׁמּות יושׁיבוּ׃Enlarge the place of thy tent, and let them stretch forth the curtains of thine habitations: spare not, lengthen thy cords, and strengthen thy stakes; for thou shalt break forth on the right hand and on the left; and thy seed shall inherit the Gentiles, and make the desolate cities to be inhabited. (Isa 54:2-3)

The Chinese Classics, although the parallel is not perfect, draw on a similar kind of wisdom for the word jian 閒. It was the dayin大淫 ‘great excesses’ or ‘great luxuries’ of the Xia that brought the wrath of Heaven down on them and led to them being jian 閒 or tian 殄 ‘cut off’ by the Shang. On the other hand, it is precisely in the proper and hospitable treatment of guests that the Book of Rites makes most use of the same word jian:

若非飲食之客,則布席,席間函丈。主人跪正席,客跪撫席而辭。客徹重席,主人固辭。客踐席,乃坐。主人不問,客不先舉。

Except in the case of guests who are there (simply) to eat and drink, in spreading the mats a space of ten cubits should be left between them. When the host kneels to adjust the mats (of a visitor), the other should kneel and keep hold of them, declining (the honour). When the visitor (wishes to) remove one or more, the host should firmly decline to permit him to do so. When the visitor steps on his mats, (the host) takes his seat. If the host have not put some question, the visitor should not begin the conversation. (Rites 《禮記》 1.30)

The point being, the host should do all possible to make his guest comfortable, and to give him room. Although the guest is also expected to uphold a certain degree of propriety, the primary consideration is for the guest’s comfort and ease. The guest is not to be expected to sit on the hard ground or to entertain the host with talk, unless there is some pressing business with the host. The ‘space’, the jian 閒 or rāḥab רחב, we occupy, in both textual corpuses, is not actually our own. We ourselves are guests, and the Host expects us to behave accordingly, with welcome.