The lexicology of lai 來 and mai 麥

He will judge the world with righteousness, and the peoples with his truth. (Psalm 95:13)

One of the oldest secular songs in the English language for which we have an extant melody is the Middle English Canon of Summer, also known as ‘Sumer is icumen in’. It’s the song that Alan Hale is whistling to himself when his character, Little John, is first seen in the 1938 film The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. The first verse goes:

Sumer is icumen in,

Lhude sing cuccu!

Groweþ sed

and bloweþ med

and springþ þe wde nu—

Sing cuccu!

Or, in modern English: ‘Summer has arrived; sing loudly, cuckoo! The seed is growing, the meadow is blooming, and the wood is turning new leaves; sing, cuckoo!’ As Waldmann notes: ‘“is icumen”, from the first line, is close to modern German “ist gekommen”, where the verb to be is used to make the perfect tense for verbs of movement and change of state’, and that appears to be true, particularly in this first verse of the song, of plants. One wonders if a similar line of thought wasn’t in the minds of the ancient Chinese when they chose to assign the function of ‘come’ to the character lai 來.

The word lai 來 (simplified 来) is the basic Mandarin word for ‘to come, to arrive, to return’, and is often used by itself in that function. However, it is also used in compounds like qilai 起来 ‘to rise up’; chulai 出来 ‘to come out’; jinlai 进来 ‘to come in’; huilai 回来 ‘to return, to come back’; guolai 过来 ‘to come across’; xialai 下来 ‘to come down’; laizi 来自 ‘to hail from’; dailai 带来 ‘to bring along’; yuanlai 原来 ‘originally, at first’; weilai 未来 ‘future’; and yilai 以来 ‘afterwards, since’. Its usage in such compounds is often to indicate movement in the direction of the speaker, or towards a state of completion.

The reason I bring up ‘Sumer is icumen in’, though, is because lai 來 is a rebus, or a loangraph (jiajie 假借), whose original pictographic function was a stalk of wheat: the top line (yi 一) representing the ear; the two crooked lines (ren 人) on either side representing the leaves; and the two diagonal strokes at the bottom (ba 八) representing the roots. The two words originally had a similar proposed ancient pronunciation: /*mrɯːɡ/. Some more recent authorities (such as Baxter and Sagart) suggest /*mə-rˤək/ for ‘wheat’ and /*rˤək/ for ‘to come’, which may explain the divergence in pronunciation. This suggestion is strengthened by comparison with cognates like Burmese la လာ ‘to come’. However, Xu Shen interprets the two words as being semantically linked: 天所來也,故為行來之來。 ‘It comes from the heavens, and so wheat is said to “come”.’ Groweþ sed and bloweþ med, indeed! By the Warring States, the function of ‘to come’ was assigned to a different character, mai 麥, which shows a ‘foot’ (sui 夊) under the phonetic ‘wheat’; however, the two characters had exchanged lexical functions again by the Han Dynasty clerical script reforms, which is how mai 麥 has come to represent ‘wheat’ while lai 來 once again functions as ‘to come’.

In the Odes, we can still see this residual usage of lai 來 as ‘wheat’: 貽我來牟、帝命率育。 ‘Thou didst confer on us the wheat and the barley, which God appointed for the nourishment of all.’ (Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Qing Miao 清廟之什, ‘Si Wen’ 思文 1) But the more common usage is simply ‘to come, to arrive’: 有來雝雝、至止肅肅。 ‘They come full of harmony; they are here, in all gravity.’ (Odes, Decade of Chen Gong 臣工之什, ‘Harmony’ 雝 1) It can also be used verbally to indicate a future, planned or desired action, or one incurred or caused by some preceding event: 至于海邦、淮夷來同。 ‘Even the states along the sea; the tribes of the Huai will seek our alliance…’ (Odes, Praise-Odes of Lu 魯頌, ‘Solemn Temples’ 閟宮 6) Or: 且也虎豹之文來田 ‘And moreover, it is the beauty of the skins of the tiger and leopard which makes men hunt them…’ (Zhuangzi 《莊子》7.4) Probably because of this usage, it was nominalised in the abstract as ‘future’: 「予恐來世以台為口實。」 ‘I am afraid that in future ages men will fill their mouths with me.’ (Book of Documents 《尚書》, Book of Shang 商書, ‘Announcement of Zhong-Hui’ 仲虺之誥 1) This usage survives in modern Mandarin compounds such as weilai 未来 and jianglai 将来.

The imperative usage of lai 來 ‘come!’ is attested in the Documents: 帝曰:「來,禹!汝亦昌言。」 ‘The Di said, “Come Yu, you also must have excellent words (to bring before me).”’ (Documents, Book of Yu 虞書, ‘Yi and Ji’ 益稷 1) From this usage, the word came to be used as a particle of emphasis or demonstration: 不念昔者、伊余來塈。 ‘You do not think of the former days, and are only angry with me!’ (Odes, Odes of Bei 邶風, ‘East Wind’ 谷風 6) This function does not survive in modern Mandarin. It can also be used as a word expressing a positive suggestion or encouragement: 雖然,若必有以也,嘗以語我來! ‘Nevertheless you must have some ground (for the course which you wish to take); pray try and tell it to me.’ (Zhuangzi 4.1) Lai 來 is still used this way in modern Mandarin, kind of like a cajoling ‘c’mon’ in English: to soften a command or to offer encouragement.

The Semitic triliteral b-w-’ ב-ו-א or ب و ء, having the basic function of ‘to come’, shares considerable overlap in range with the modern Mandarin usages of the word lai 来. For example: כּי בּא החלום בּרב ענין וקול כּסיל בּרב דּברים ‘For a dream comes with much business, and a fool’s voice with many words’ (Ecc 5:3). Here, bô’ בוא functions much like Mandarin dailai 带来 ‘to bring’. And here: ויהי משׁקל הזּהב אשׁר־בּא לשׁלמה בּשׁנה אחת שׁשׁ מאות ושׁשּׁים ושׁשׁ כּכּרי זהב ‘Now the weight of gold that came to Solomon in one year was six hundred and threescore and six talents of gold’ (2 Par 9:13), the function of bô’ is ‘to return’, similar to Chinese huilai 回来, though more specifically to Chinese huibao 回报 ‘return (on investment)’. Also: והבאתי אתכם אל־הארץ אשׁר נשׂאתי את־ידי לתת אתהּ לאברהם ‘And I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham’ (Exo 6:8) mirrors the modern Chinese functions of guolai 过来 and jinlai 进来. In addition, the conjugal usage of bô’, as in: בּא־נא אל־שׁפחתי אוּלי אבּנה ממּנּה ‘go in to my maid; it may be that I shall obtain children by her’, is reflected in the Odes’ now-archaic use of lai 來 for a lover ‘coming to’ his beloved, or a husband ‘coming to’ his wife (as in ‘Male Pheasant’ 雄雉 3, ‘Blue Collar’ 子衿 2, ‘Solitary Pear’ 有杕之杜 2).

However, the Classical usage of lai 来 modifying an action to show it is planned, desired or predicted, is also attested in Genesis’s use of bô’ בוא: ויּאמר אלהים לנח קץ כּל־בּשׂר בּא לפני ‘And God said to Noah, “I have determined to make an end of all flesh”’ (Gen 6:13); though, the literal usage of bā’ lǝfānay בוא לפני here is ‘come before my face’. This usage of bā’ باء as ‘to incur’ is also seen in Qur’ānic Arabic: وباءو بغضب من الله وضربت عليهم المسكنة ‘And they have drawn upon themselves anger from God and have been put under destitution’ (3:112).

There are some notable differences between Sinitic and Semitic grammar systems, which constrain the validity of these comparisons. Modern Mandarin extends the semantic range of lai 来 through compounding, whereas Semitic languages achieve similar effects through derivational morphology (as in the hif‘il form הביא ‘to bring’) and base-stem alterations. Likewise, the two language families diverge in their treatment of verbal aspect. Even in Classical Chinese, lai 来 is grammaticalised to mark directional or inceptive aspect, as b-w-’ ב-ו-א is not, in any Semitic language. Also, because the two textual corpora reflect divergent cultural perspectives, the connotative ranges of these two lexemes differ despite functional overlaps. In conjugal contexts, for example, lai 来 is read as coquettish, even playful. Bô’ בוא, by contrast, is a neutral or even slightly-pejorative euphemism: Sarah can hardly be read as happy in offering Hagar to her husband!

The lai 來 of the Chinese Classics, which functions as an auxiliary to the verb, though, carries a parallel connotation to bô’ בוא. Observe Psalm 95:

ישׂמחוּ השּׁמים ותגל הארץ ירעם היּם וּמלאו׃

יעלז שׂדי וכל־אשׁר־בּו אז ירנּנוּ כּל־עצי־יער׃

לפני יהוה כּי בא כּי בא לשׁפּט הארץ ישׁפּט־תּבל בּצדק ועמּים בּאמוּנתו׃Let the heavens be glad, and let the earth rejoice; let the sea roar, and all that fills it;

let the field exult, and everything in it! Then shall all the trees of the wood sing for joy

before the Lord, for he comes, for he comes to judge the earth. He will judge the world with righteousness, and the peoples with his truth. (Psalm 95:11-13)

The end of Psalm 95 makes reference to the Day of Judgement, a Day which is planned and which will surely come, but which cannot be predicted or prepared for by the human being. The Day is one of promise of justice for the ‘ammîm עמּים, which the RSV translates in a rather anodyne way as ‘the peoples’, but which connotes instead a collective, a multitude, a mixed herd. It is used specifically to refer to those who are not princes, or priests, or military commanders: it refers to the commons. I find it interesting because there is another among the Odes that uses lai 來 in such a way:

爾牧來思、以薪以蒸、以雌以雄。

爾羊來思、矜矜兢兢、不騫不崩。

麾之以肱、畢來既升。Your herdsmen come,

With their large faggots, and smaller branches,

And with their prey of birds and beasts.

Your sheep come,

Vigorous and strong,

None injured, no infection in the herd.

At the wave of the [herdsman’s] arm,

All come, all go up [into the fold].(Odes, Decade of Qi Fu 祈父之什, ‘No Sheep’ 無羊 3)

This is the third stanza of a paean to an unnamed future prince, presently poor and obscure (hence the title of the Ode), whose prosperity and halcyon rule is prophesied by the herdsmen (mu 牧) and interpreted by the chief diviner (da ren zhan zhi 大人占之): that the multitudes (zhong 眾, parallel here to ‘ammîm עמּים) will be well-fed and happy, and that they will multiply. The eschatological tenor of ‘No Sheep’ is implicit in the final stanza. But the approach of this end is attested by the repetition of lai 來 here. A similar implication of a future state of justice and harmony approaching the way of Heaven is made in the Rites, called the Datong 大同 ‘Grand Union’ (Rites 《禮記》 9).

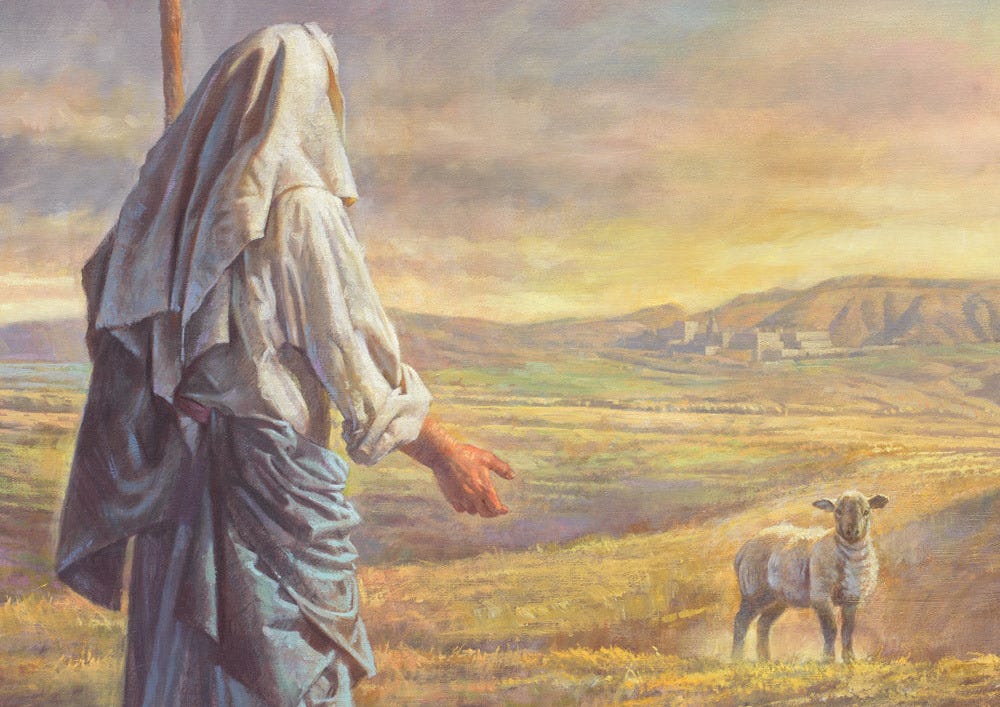

The grammatical distinctions between the two texts, written in two distinct languages and coming from two distinct cultures, are still intriguing. That lai 來 is an auxiliary to other verbs (si 思 ‘to gather’; sheng 升 ‘to go up’) in the Chinese text, while operating emphatically and independently in the Semitic one, is significant. The Psalm assigns purpose; the Ode leaves that purpose implicit. But both the repeated lai 來 of ‘No Sheep’ and the repeated bô’ בוא of Psalm 95 invoke an inevitable coming of divine intervention. And both textual pericopes highlight the zhong 眾 or the ‘am עם, the mixed-multitude, the collective, the commons, as the beneficiaries of the justice and harmony that will result from this intervention. What is interesting about ‘No Sheep’ is its explicit pastoralism: a distinct oddity in a textual corpus that is on the whole much friendlier to settled, agrarian lifestyle.

The pastoral imagery in ‘No Sheep’ may, indeed, quietly critique agrarian complacency. Just as shepherd metaphors are used regularly in the Hebrew Scriptures to chastise the institution of kingship (e.g. Ezekiel 34:2–10), the Odes’ herdsmen suggest a mobile, virtuous authority that transcends fixed, worldly hierarchies.