The lexicology of rong 容

As for me, I shall behold thy face in righteousness; when I awake, I shall be satisfied with beholding thy form. (Ps 16:15)

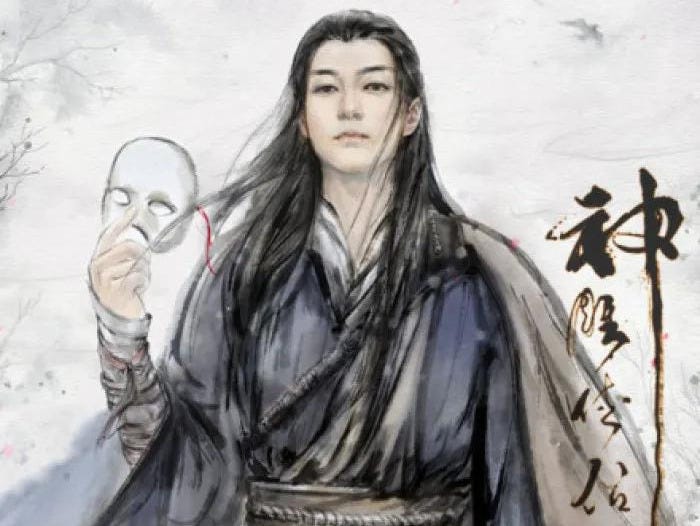

I’m a big fan of Louis Cha’s wuxia novels, particularly the Condor trilogy. Written in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s, these books take place during the late Song Dynasty just before its collapse and conquest by the Mongol Empire—which in China is known as the Yuan Dynasty. The hero of the first book, Guo Jing 郭靖, is named after the Jingkang Incident (Jingkang Shibian 靖康事变) wherein the Emperor and many of his kinsmen were kidnapped and held for ransom by the Jurchen Jin—a massive humiliation for the Chinese dynasty. He is raised by Mongols, but returns to the Song in order to avenge the wrongful death of his father Guo Xiaotian. His love interest in the story is Huang Rong 黄蓉, the young daughter of a heretical but powerful martial-arts master.

Guo Jing is a direct and uncomplicated character—something most other people in the wulin (武林, the martial-arts subculture or world of heroes and outlaws) mistake for stupidity—but Huang Rong is quite the opposite. When she first appears in the story, she is in disguise as a beggar boy, which is how she befriends Guo Jing. She is incredibly knowledgeable on account of her father’s education; but she is also a bit spoiled and naïve on account of her sheltered upbringing. But her deeply logical mind as well as her wiles and talent for subterfuge help both her and Guo Jing get out of a number of tight spots throughout the story. Because of her original disguise, she was able to fool Guo Jing into thinking she was a boy, and throughout the story, her opponents underestimate her for her looks—while she herself is often able to see into the substance of things.

Huang Rong’s name (rong 蓉) is used to refer to a kind of hibiscus or lotus flower (furong 芙蓉) or else to a finely-minced paste made from lotus root and other ingredients, that is used as filling (xian 馅) in pastries. This word belongs to the same etymological series of words as rong 容 ‘looks, appearance, figure, form’, which provides both its graphical appearance and its phonetic value. This makes sense, because it is the filling that gives a pastry its shape!

This allied word rong 容 is used in a number of compounds in modern Mandarin: rongyi 容易 ‘simple, easy, facile’; neirong 内容 ‘contents (of a container or a book)’; xiaorong 笑容 ‘smiling face’; xingrong 形容 ‘to describe’ and xingrongci 形容词 ‘adjective’; rongren 容忍 ‘to endure, to tolerate’; meirong 美容 ‘to beautify’; kuanrong 宽容 ‘lenient, liberal, broadminded’; rongliang 容量 ‘volume, capacity’; rongqi 容器 ‘container, (programming) variable, (electrical engineering) capacitor’.

The Erya 《尔雅》 defines rong 容 as a synonym of wei 謂 ‘meaning, proposition, predicate’. And Xu Shen defines it as a synonym of cheng 盛 ‘to hold, to put inside, contents of a container’. It is a phono-semantic glyph, with the mian 𰃦 ‘roof’ radical providing the semantic value and with the pronunciation derived from gu 谷 ‘valley, gorge’ or (more likely) gong 公 ‘public, shared’.

If it can be believed, the semantic range of rong 容 in the Classics is even broader than it appears in its modern form! It can function as an adjective, ‘easy, at ease, nonchalant’: 容兮遂兮、垂帶悸兮。 ‘How easy and conceited is his manner, with the ends of his girdle hanging down as they do!’ (Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Wei 衛風, ‘Sparrow-Gourd’ 芄蘭 1-2) Or: 寬而有制,從容以和。 ‘Be gentle, but with strictness of rule. Promote harmony by the display of an easy forbearance.’ (Documents 《尚書》, Book of Zhou 周書, ‘Jun-Chen’ 君陳 2) It can also function as a verb ‘to fit, to contain’ or ‘to make up, to adorn’: 誰謂河廣、曾不容刀。 ‘Who says that the He is wide? It will not admit a little boat.’ (Odes, Odes of Wei, ‘The Wide He’ 河廣 2) Or: 誰適為容? ‘For whom should I adorn myself?’ (Odes, Odes of Wei, ‘My Noble Husband’ 伯兮 2)

Still yet it can function as a noun, ‘appearance, demeanour, mien’: 其容不改、出言有章。 ‘Their deportment unvaryingly [correct], and their speech full of elegance!’ (Odes, Decade of Du Ren Shi 都人士之什, ‘Old Capital Officers’ 都人士 1), or 我客戾止、亦有斯容。 ‘My visitors came, with an [elegant] carriage like those birds.’ (Odes, Decade of Chen Gong 臣工之什, ‘Egrets’ 振鷺 1) In the Changes, the most common usage of rong 容 is as a verb, ‘to bear with, to endure, to sustain’: 突如其來如,無所容也。 ‘“How abrupt is the manner of his coming!” – none can bear with him.’ (Changes 《易經》, ‘Li’ 離 5) And in the Rites, the most common usages of rong 容 are, as above, ‘demeanour’ or else ‘behaviour’, in a more moralistic sense: 有不戒其容止者,生子不備,必有凶災。 ‘If any of you be not careful of your behaviour, you shall bring forth children incomplete; there are sure to be evils and calamities.’ (Rites 《禮記》6.15)

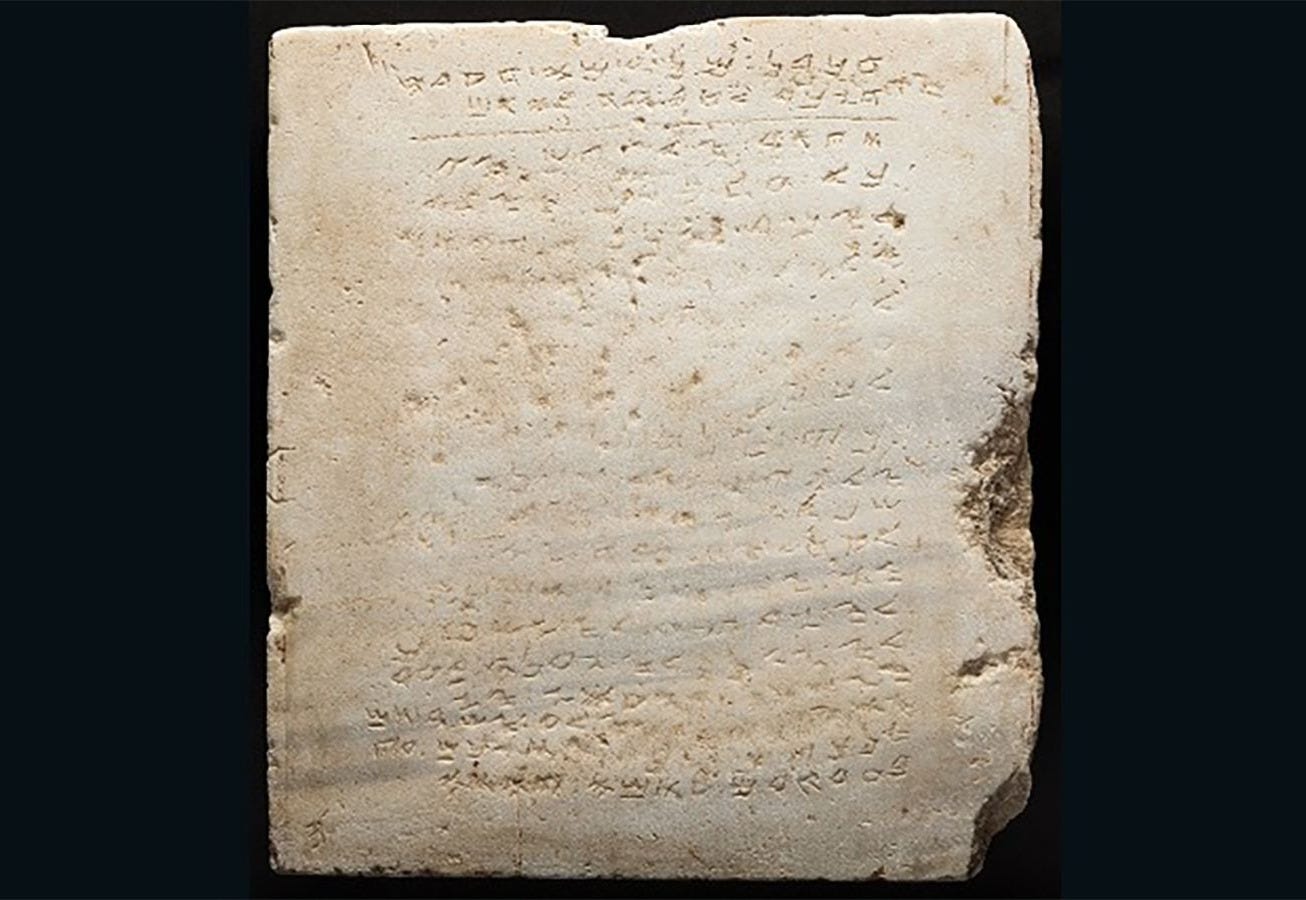

The Hebrew word tǝmûnâ תמונה is used in the Old Testament to refer to the ‘form’ of an object—that is to say something ‘fashioned’ or ‘apportioned’ (from the Hebrew root m-y-n מ-י-ן ‘to apportion, sort, kind’) into a particular shape. It can also mean anything that ‘appears’ or presents itself in that shape: a ‘likeness’ or ‘semblance’. This usage of the Semitic tǝmûnâ תמונה thus overlaps and connects with the Sinitic word rong 容 in two (possibly three) limited senses: firstly, with the ‘appearance, deportment or mien’; and secondly, with the verbal form ‘to make up, to adorn’ and (much more loosely) ‘to fit’. In most instances in which tǝmûnâ תמונה appears in Scripture, its connotation is negative. It refers to the wrongful ‘semblance’ which belongs to an idol, an image hollowed-out or ‘fashioned’ to appear as something worthy of worship:

לא תעשׂה־לך פסל וכל־תּמוּנה אשׁר בּשּׁמים ממּעל ואשׁר בּארץ מתּחת ואשׁר בּמּים מתּחת לארץ׃

You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. (Exo 20:4)

But not all instances are negative. God summons Aaron and Miriam after they try to undermine Moses and complain about him being married to a foreigner (Ṣiffûrâ צפורה, who is here described as ‘Ethiopian’ though in Exodus she is portrayed as a woman of Midian). God tells them:

פּה אל־פּה אדבּר־בּו וּמראה ולא בחידת וּתמנת יהוה יבּיט וּמדּוּע לא יראתם לדבּר בּעבדּי במשׁה׃

With him I speak mouth to mouth, clearly, and not in dark speech; and he beholds the form of the Lord. Why then were you not afraid to speak against my servant Moses? (Num 12:8)

The point in this instance is that Moses is privileged above all other men, and his authority is not to be questioned even by his own family. God chooses to reveal some semblance or appearance of Himself to Moses, that He is not willing to show to anyone else directly. And therefore it is out of line for Aaron and Miriam to try to undercut his authority, let alone to be racist douchebags and upbraid him for marrying a foreigner.

The same lexeme appears in both its approbative and pejorative senses… in Deuteronomy (ch. 4 and 5)! It is an extended warning to the Hebrews that when they received the Law they saw no form of the One Who gave it to them, only hearing a voice from out of the fire. Thus they are not permitted to fashion any ‘likeness’ of Him, as it will ultimately be a false semblance! After all: how can you ‘form’ or ‘shape’ or ‘apportion’ something like fire—let alone Him Who could not even be directly perceived through it? The auxiliary point is that because the Lawgiver does not present Himself in any of these visible forms, the Law therefore does not speak as a human speaks, or a beast, or a bird. It is delivered as a purely consonantal text in a Semitic abjad, which must be studied and understood before it is read aloud! The form of the Law does not admit (as an image or idol would) of a passive or thoughtless reception by the eyes, but rather demands careful study.

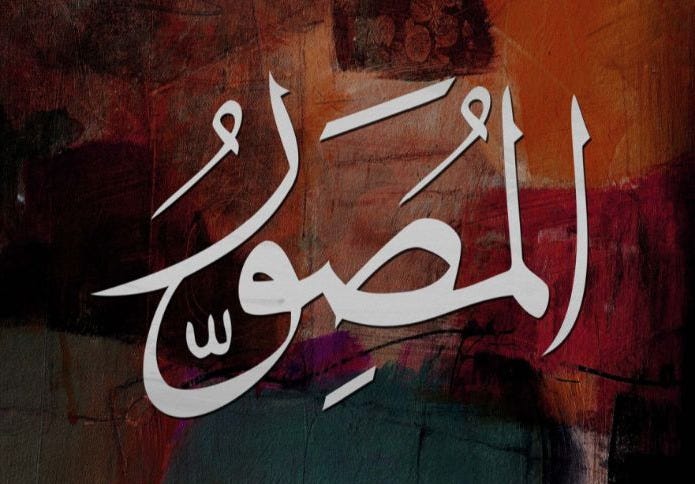

And this leads to another point. The parallel operative root in Syriac—and thus in Arabic—is ṣ-w-r ܨ ܘ ܪ or ص و ر. The verbal forms associated with this root include ‘to form, to shape, to fashion, to incline’, and in Syriac the nominal forms associated with it include ‘image, portrayal’. But they function in the same way that the Hebrew m-y-n מ-י-ן does, in the sense that a material is being apportioned: that is to say, ‘to enclose, to bind up, to cast (in a mould), to confine, to wrap up’. (Note the point of connexion with the Sinitic rong 蓉 here in its function as the ‘filling’ of a dumpling or a pastry!) In the Syriac Pǝšiṭta, the term ṣûrṭa’ ܨܽܘܪܬ݁ܳܐ glosses the Greek σύμμορφος ‘to mould, to fashion into the shape of, to conform to’ as in Romans 8:29:

ὅτι οὓς προέγνω καὶ προώρισεν συμμόρφους τῆς εἰκόνος τοῦ υἱοῦ αὐτοῦ εἰς τὸ εἶναι αὐτὸν πρωτότοκον ἐν πολλοῖς ἀδελφοῖς

ܘܡܶܢ ܠܽܘܩܕ݂ܰܡ ܝܺܕ݂ܰܥ ܐܶܢܽܘܢ ܘܰܪܫܰܡ ܐܶܢܽܘܢ ܒ݁ܰܕ݂ܡܽܘܬ݂ܳܐ ܕ݁ܨܽܘܪܬ݁ܳܐ ܕ݁ܰܒ݂ܪܶܗ ܕ݁ܗܽܘ ܢܶܗܘܶܐ ܒ݁ܽܘܟ݂ܪܳܐ ܕ݁ܰܐܚܶܐ ܣܰܓ݁ܺܝܶܐܐ ܀

For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the first-born among many brethren. (Rom 8:29, RSV)

It is God who shapes men into the mould of Christ! And further, observe that the noble Qur’ān uses the same root in Arabic, in the same way that Saint Paul does in his letter to the Romans (who clearly did not ‘get the message’). God is al-Muṣawwiru المصور, ‘the Fashioner’ (59:24:5), from which it is naturally presumed that we are the ones ‘fashioned’ by Him, and that He is not to be ‘fashioned’ after anything else. The teaching that connects Deuteronomy to Romans to Surah 59 is an aniconic teaching, which is particularly ironic given that the one expositing it (yours truly) is an Orthodox Christian who happens to love icons.

The Odes do not say exactly the same thing about the One Who is in Heaven, in exactly the same words as the Abrahamic texts, but they do warn:

蕩蕩上帝、下民之辟。

疾威上帝、其命多辟。How vast is God,

The ruler of men below!

How arrayed in terrors is God,

With many things irregular in His ordinations!

(Odes, Decade of Dang 蕩之什, ‘Vast’ 蕩 1)

And:

上帝甚蹈、無自暱焉。

俾予靖之、後予極焉。God is very changeable,

Do not approach him.

If I were to [try and] order his affairs,

His demands afterwards would be extreme.

(Odes, Decade of Sang Hu 桑扈之什, ‘Luxuriant Willow’ 菀柳 1)

The use of ‘changeable’ here on Legge’s part is questionable: the term dao 蹈 refers to a ‘step’ or a ‘tread’ (cf. the hālak הלך motion of God in Genesis 3:8). The Ode is better understood as implying that God can ‘step’ or ‘tread’ further and longer than any mortal being. But the broader message is: don’t try to fathom God with your mind, human. Don’t get all up in God’s bu’ness. It won’t end well for you.

It seems like Louis Cha partially intuited this as well, though of course he was writing a popular martial-arts novel for his newspaper, and not doing any kind of lexicology of classical Chinese. Even though Huang Rong was able to see through her enemy Yang Kang’s 楊康 crafty appearances and tear through his carefully-tended shroud of falsehoods with her penetrating insight, she very badly misjudged the character of Yang Kang’s young child Yang Guo 楊過 by mentally forcing him into Yang Kang’s mould. Even though Yang Guo inherited much of his father’s natural cleverness and disdain for established rules, his motives were far more selfless and noble. Huang Rong’s detestation of the father led her to play God—to mistreat and even emotionally abuse the son, and contributed significantly to his sufferings in the second novel.

It is a rather interesting exercise to reread Louis Cha’s novel in an era when Palestine, a nation of mostly children, is being collectively punished by the governments of the West for the sins of their fathers. Let us adequately reflect on the dangers of reliance on the rong 容, and the temptation to build for ourselves tǝmûnôt תמונות in judgement of those who come after us.

سبحان الله الذي لا نرى صورته. Glory be to Him Whose form we cannot see.

A friend of mine who is a doctor from Gaza (now in Egypt) is asking for some financial help for his family. They’re in pretty hard straits, and even small-volume contributions would be really helpful for them getting their bearings and getting back on their feet. Here is the GoFundMe link: https://www.gofundme.com/f/give-hope-love-to-a-gazan-family. Please consider donating.