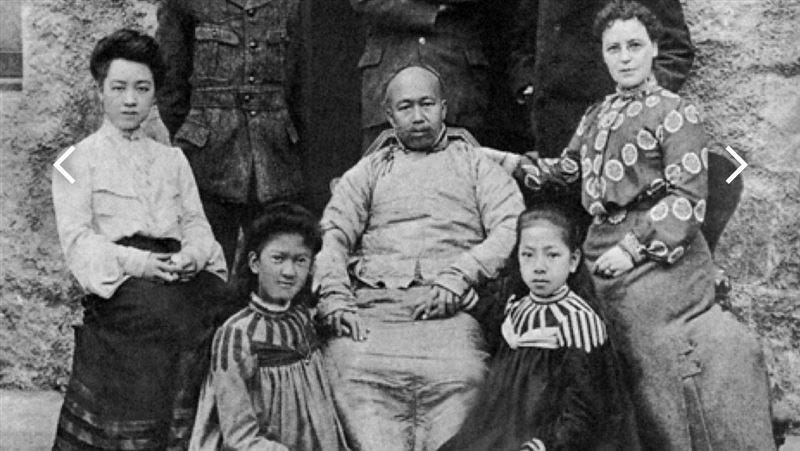

I’ve made no secret of the fact that one of the modern Ritual Scholars for whom I have a very deep respect is Kang Youwei 康有爲. Kang Youwei is still massively controversial among modern Chinese people and in the diaspora, for a number of reasons… not all of them worthy.

He was detested in his professional ascendancy among the Chinese literati, because he was one of the few among their number who dared to advocate for much-needed progressive constitutional reforms in China. He agitated against the cruel cultural practice of foot-binding, and supported causes like the modernisation of the Qing Army and mass education of the peasantry. He also wrote the Book of Great Unity, which is considered the first Chinese political treatise advocating socialist economics. Because of his involvement in the Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898, as a result of a coup by the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi, his family and friends were persecuted and he himself was driven into exile in Japan.

When he returned to China after the fall of the Qing Dynasty, his support for a constitutional monarchy rendered him, in the eyes of Sun Yat-sen’s Republicans, an obsolete relic. He supported a failed monarchist counterrevolution in 1917, which irreparably soiled his reputation in the eyes of China’s revolutionaries. Only later, after the Communists came to power, did Kang’s reputation begin to recover – but only selectively. Mao Zedong regarded him an important precursor to Chinese socialism, but no more than that.

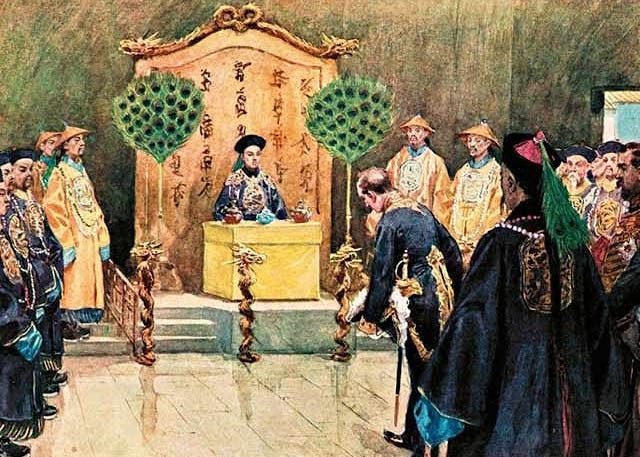

In modern times, Kang’s reputation has been besmirched at the hands of British popular novelist Jung Chang. In her highly-selective view, motivated by liberal-feminist ‘girlboss’ ideology rather than scholarship, Kang Youwei is cast as a scheming, conniving male-chauvinist villain seeking to usurp power from Empress Dowager Cixi—the ruthless imperatrix who, in Jung Chang’s mendacious rendition, is the real author of all the progressive reforms that Kang is given credit for. Academic historians better trained than I am have already given Jung Chang’s risible fanfic the shredding it richly deserves, so I’m not going to dwell too much on that.

Despite my respect for Kang Youwei, I do have some profound disagreements with the man. Kang’s best work is found in his calligraphy, in lexicography, in philology and textual studies… not so much in philosophy or political theory. Despite being a sympathetic ‘lefty’, I don’t hold with Kang’s unidirectional understanding of historical progress, nor with his overly-optimistic view of human nature. But my view of Confucius as a prophet, rather than as a philosopher, agrees with Kang Youwei’s. This is because both of us read the original Chinese texts of the Classics as works of literature rather than as history.

To do honour to Kang Youwei 康有爲 in a fashion I hope he’d appreciate, I will make a philological examination of his name. I’ve already talked a bit about the character you 有 ‘to have, to possess, to exist’. This entry will analyse the second character in his name, wei 爲 (simplified as 為 or 为) ‘to do, to make, to create, to build, to plant, to grow, to govern, to serve as, to become, for, as, alias’.

As might be expected from a word with this gargantuan a semantic range, wei 爲 is the 18th most common character in Chinese writing. On its own, it is usually glossed as ‘as’, or ‘to act as’ or ‘to serve as’. It is used in two necessary phrases in spoken Chinese: weishenme 为什么 ‘why?’ and yinwei 因为 ‘because’. It is also used in compounds such as renwei 认为 ‘to acknowledge, to believe’; weile 为了 ‘in order to’; chengwei 成为 ‘to grow into, to become’; yiwei 以为 ‘to (mistakenly) believe’; zuowei 作为 and xingwei 行为 ‘action’; weiren 为人 ‘demeanour, manners’; and also in the construction dao… weizhi 到。。。为止 ‘up to the point that; until’.

According to Xu Shen in the Shuowen jiezi, the character wei 爲 is a pictographic representation of a female monkey (muhou 母猴) with her hand (zhua 爪) stretched over her head. In his view, the rationale for this was that monkeys are good at catching birds with their hands. Most modern lexicographers, pointing to the Shang oracle-bone and bronze inscriptions, interpret the character as a syssemantograph. They are agreed with Xu Shen that the upper element represents a hand (you 又), but interpret the lower element as an elephant (xiang 象), which is being led to do work.

The usage of this character in the Classics is as broad and as varied as its usage in modern Chinese. The Ode ‘Dolichos Spreads’ 葛覃, for example, shows us a typical usage of wei in a verbal function:

葛之覃兮、施于中谷。

維葉莫莫、是刈是濩。

為絺為綌、服之無斁。How the dolichos spread itself out,

Extending to the middle of the valley!

Its leaves were luxuriant and dense.

I cut it and I boiled it,

And made both fine cloth and coarse,

Which I will wear without getting tired of it.(Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Zhou and the South 周南, ‘Dolichos Spreads’ 葛覃 2)

In its most basic functionality, wei 爲 is the action of taking some raw material (in this case, the shrubby legume dolichos) and creating something (cloth, both fine and coarse) out of it. This same sense of ‘to make’ (a refined material out of a crude one) is easily abstracted. Elsewhere we see the construction 以我為讎 ‘you even count me as an enemy’ (Odes, Odes of Bei 邶風, ‘East Wind’ 谷風 5) or 我以為兄 ‘I consider him my brother’ (Odes, Odes of Yong 鄘風, ‘Boldly Faithful…’ 鶉之奔奔 1)—with wei serving as ‘make of me’ or ‘make me out to be’; here we see the roots of the modern compound yiwei 以为 ‘to (mistakenly) believe, to consider as true’. And in its broader sense of ‘to do’, we see: 天實為之 ‘Heaven has done it!’ (Odes, Odes of Bei, ‘North Gate’ 北門 1).

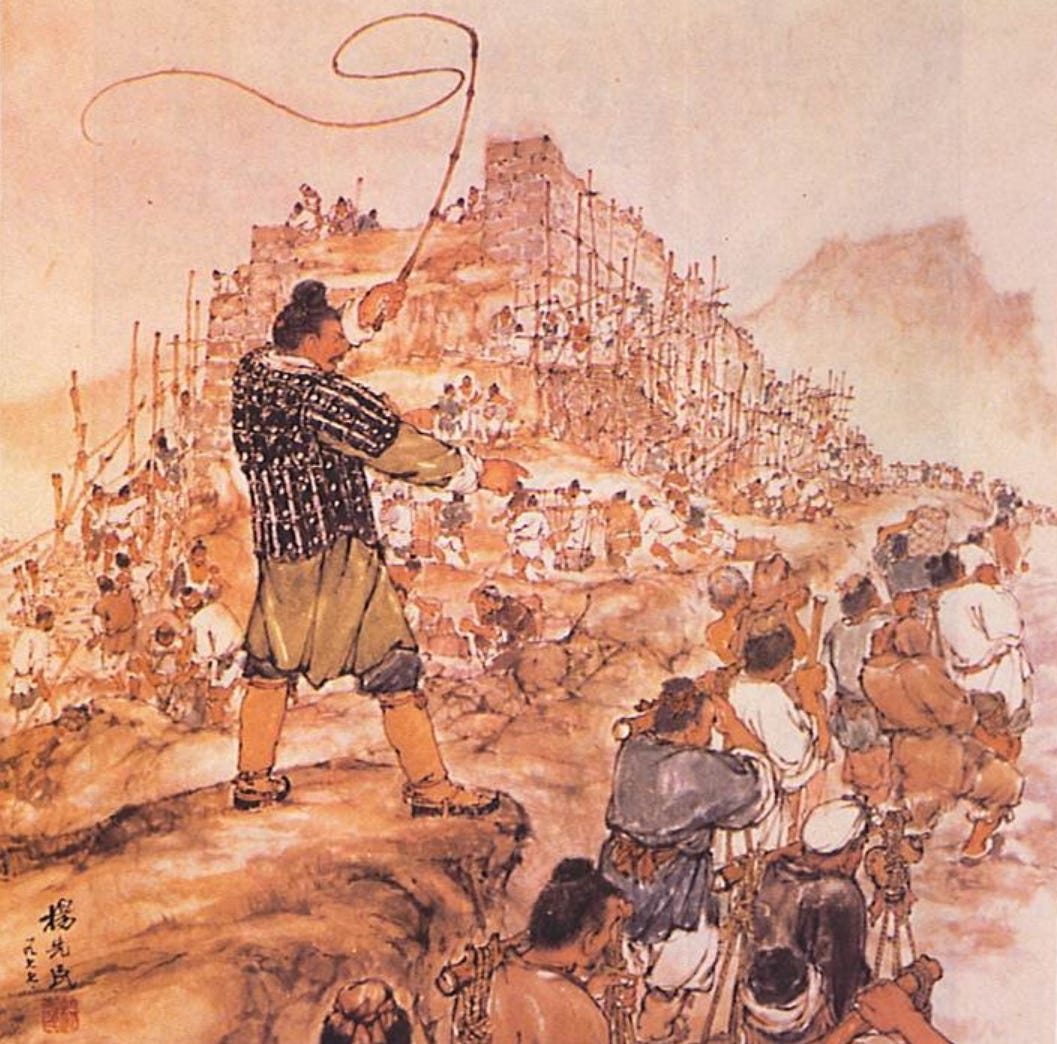

From its basic functionality, also, of ‘to make something refined out of some raw material’, we have wei 爲 serving as ‘to build, to found’ (the implication being, to make walls and roofs out of the raw material of earth) and also ‘to cultivate’ (to make farmland out of fallow) and ‘to govern’ (to make order out of chaos). For example: 為山九仞,功虧一簣。 ‘In raising a mound of nine fathoms, the work may be unfinished for want of one basket (of earth).’ (Documents 《尚書》, Book of Zhou 周書, ‘Hounds of Lu’ 旅獒 2) Also: 度其隰原、徹田為糧。 ‘He measured the marshes and plains; he fixed the revenue on the system of common cultivation of the fields.’ (Odes, Decade of Sheng Min 生民之什, ‘Duke Liu’ 公劉 5) And here: 王啟監,厥亂為民。 ‘When sovereigns appointed overseers (of states), they did so in order to the government of the people.’ (Documents, Book of Zhou 周書, ‘Timber of the Rottlera’ 梓材 2)

The same set of functionalities (‘to do, to make, to create, to take as, to consider’) can be expressed in passive voice. Thus wei 爲 can be as much ‘to be made of, to serve as, to count as, to be called, to become’: 高岸為谷、深谷為陵。 ‘High banks become valleys; deep valleys become hills.’ (Odes, Decade of the Minister of War 祈父之什, ‘Conjunction in the Tenth Month’ 十月之交 3: a very Isaian-sounding passage!) Or: 受小球大球、為下國綴旒。 ‘He received the rank-tokens [of the States], small and large, which depended on him, like the pendants of a banner.’ (Odes, Sacrificial Odes of Shang 商頌, ‘Long Appeared’ 長發 4)

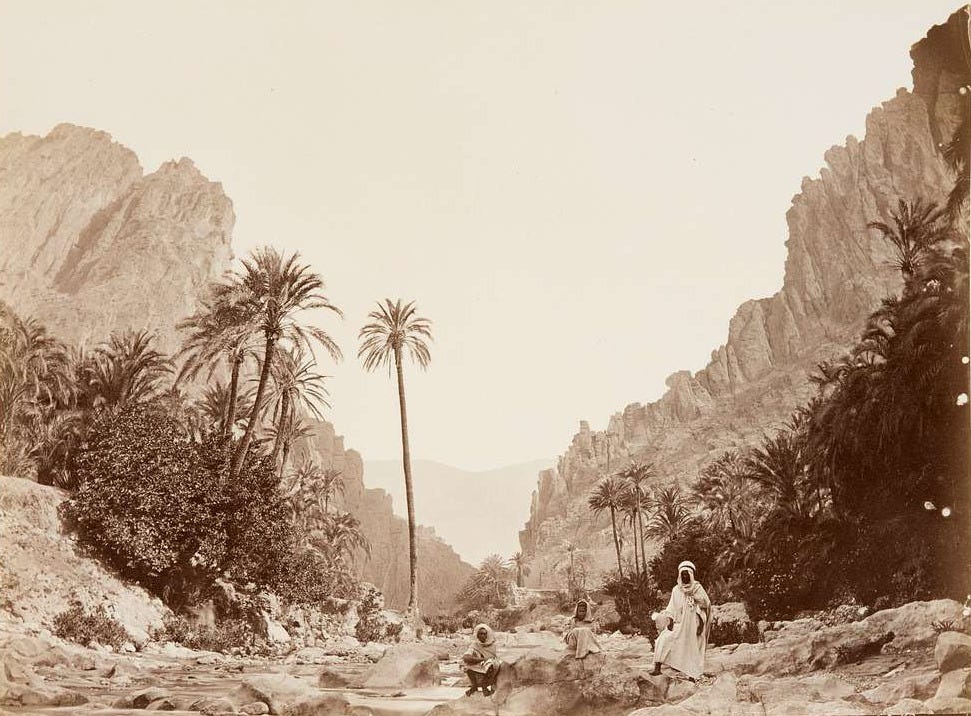

In my book The Lamb Before Its Shearers (available for purchase wherever books are sold, though I would prefer you buy it from an actual bookseller, rather than from Amazon), I point to the fact that Hebrew has several roots which can function as ‘to do’ or ‘to make’. Among these is fā‘al פעל, which comes from a common Semitic root f-‘-l פ-ע-ל. This root has descendants all over the place. In Classical Syriac, pe‘al ܦܥܠ means ‘to work, to labour’; this root shows up in the Pǝšiṭta New Testament, most frequently in the Gospel of Matthew. In Qur’ānic Arabic, fa‘al فعل carries the basic verbal function of ‘to do, to deal with, to accomplish’, but it also serves in the functions of ‘deed, doer, executed, fulfilled, destined’. One of the related nouns here, actually—borrowed from Syriac and allied to the Chinese function of wei 爲 as ‘to cultivate’—is fallāḥ فلاح ‘peasant, farmer’.

In the Psalms, though, the root f-‘-l פ-ע-ל is almost always used in a pejorative sense when applied to people, because it forms part of the stock phrase fō‘alê ’āwen פעלי און ‘workers of iniquity, lit. evil-doers’ (Ps 5:6, 6:9, 13:4, 27:3, 35:13, 52:5, 57:3, 58:3, 63:3, 91:8-10, 93:4,16, 100:8, 118:3, 124:5, 140:4,9). The direct implication, of course, is that these are the human beings who dig pits (e.g. Ps 7:16) and set traps (140:9) for their fellow human beings in hope of profiting off of them. But the inescapable underlying subtext is: the evil is in the work itself if it is to the glory of man! Only God is permitted to build, to create works in this sense, because out of this work He does not entrap or seek profit but instead helps and liberates (Ps 43:2, 73:12, etc.). This is the exact same function in which St Paul castigates the Jordan Petersons of his day, the ‘workers of deception’ (Syr. ܘܦ݂ܳܥܠܶܐ ܢܟ݂ܺܝܠܶܐ wǝpa‘le’ nǝkîle’, Gk. ἐργάται δόλιοι) who build their own reputations alongside his, and preach a different Christ for their own aggrandizement (2Cor 11:13).

This same teaching can be seen, in part, in the Book of Exodus, in the Song of Moses and Israel:

תּבאמו ותטּעמו בּהר נחלתך מכון לשׁבתּך פּעלתּ יהוה מקּדשׁ אדני כּוננוּ ידיך׃

Thou wilt bring them in, and plant them on thy own mountain, the place, O LORD, which thou hast made for thy abode, the sanctuary, O LORD, which thy hands have established. (Ex 15:17)

The corollary is clear here, for those with ears to hear it: man can build no sanctuary for the God Who has Himself wrought the whole of the earth (not just this mountain) for His dwelling! This is the same function as the rock cut by no human hand in the Book of Daniel (different root—g-z-r ג-ז-ר—same function in the text), which crushes all of the fine building-materials and decorations which the princes of this world use to enrich their palaces and temples (Dan 2:45). Hear this and weep if you can, O you self-serving ‘Judeo-Christians’ of the West, whose hands are dripping in Palestinian blood! This is your own text speaking to you and witnessing against you!

And wouldn’t you know it? The Qur’ān says the exact same thing, even in the same words as St Paul:

وكذلك جعلنا لكل نبي عدوا شياطين الإنس والجن يوحي بعضهم إلى بعض زخرف القول غرورا ولو شاء ربك ما فعلوه فذرهم وما يفترون

And so We have made for every prophet enemies—devilish humans and jinn—whispering to one another with elegant words of deception. Had it been your Lord’s Will, they would not have done such a thing. So leave them and their deceit! (6:112)

(Note that adjectives like zuḵrufa زخرف, which can function as ‘elegant’, ‘ornamental’ or ‘(made of) gold’, are deliberately redolent of Daniel and of Old Testament descriptions of Temple adornments, the embellishments on buildings!)

A couple words about wu wei 無爲. This phrase cannot be said to be an invention of the Matrical School. Because this phrase was already present in the Odes, it was therefore common to both the Ritual and Matrical Schools:

天之方懠、無為夸毗。

威儀卒迷、善人載尸。Heaven is now displaying its anger;—

Do not be either boastful or flattering,

Utterly departing from all propriety of demeanour,

Till good men are reduced to personators of the dead.(Odes, Decade of Sheng Min, ‘Reversal’ 板 5)

Here it has nothing to do with philosophy. Wu wei 無爲 is made into this profound philosophical ideal of ‘effortless action’ or ‘creative inaction’ even in the most basic of English-language commentaries on the Daodejing 《道德經》. And so poisoned are we by philosophy that we do not see the irony in this! But, obnoxious as the hippy-dippy New Agers are, this isn’t solely the fault of Alan Watts and Br Seraphim Rose and that whole crowd of Western enthusiasts. The followers of the Matrical School did it, in significant measure, to themselves. When they became a Daoist institution, they built temples to Laozi, to teach disciples about Laozi’s wisdom of not building. It’s ridiculous.

Here in the Odes we can see the phrase wu wei 無爲 being used as essentially a summation of Wheaton’s Law: ‘Don’t be a dick.’ Don’t boast. Don’t puff yourself up. Don’t be a flatterer. Don’t usurp Heaven’s authority. Don’t compromise yourself. Don’t connect or adjoin or erect supports to any human structure (that’s the function of both wei 爲 and bi 毗 here). Don’t get full of yourself, human!

In short: don’t be Empress-Dowager Cixi, and don’t be a simpering apologist for power like her biographer! Better to be a Kang Youwei who writes calligraphy and tends gardens and teaches the Classics, than a spoilt late-Imperial Manchu princess who uses the sweat and toil and treasure of her people to build a summer palace for her birthday (that then gets razed to the ground and plundered by the British).

Subḥān Allāh al-Wāḥida al-’Aḥad, yafa‘l mā yašā’.

سبحان الله الواحد الأحد، يفعل ما يشاء