The only ṭûr ’ahabôt worth discussing...

... and what we Orthodox somehow manage to get right about the στιχηρά

During Saturday Vespers, and during Sunday Orthros (if you arrive early enough to Church to hear them), we have in the Orthodox Church a genre of hymnology called the stichera. The name of these hymns comes from the Greek word στιχηρά meaning ‘arrayed in lines’. They are so called because they are meant to be sung between the Old Testament readings for the week, similar to the spaces between ranks in an army marching in formation. This word appears in only two books of the Greek Septuagint—in Exodus, and in the First Book of Kings. For example:

καὶ ἐφάτνωσεν τὸν οἶκον ἄνωθεν ἐπὶ τῶν πλευρῶν τῶν στύλων καὶ ἀριθμὸς τῶν στύλων τεσσαράκοντα καὶ πέντε δέκα καὶ πέντε ὁ στίχος

וספן בּארז ממּעל על־הצּלעת אשׁר על־העמּוּדים ארבּעים וחמשּׁה חמשּׁה עשׂר הטּוּר׃

And it was covered with cedar above the chambers that were upon the forty-five pillars, fifteen in each row. (1 Kings 7:3, RSV)

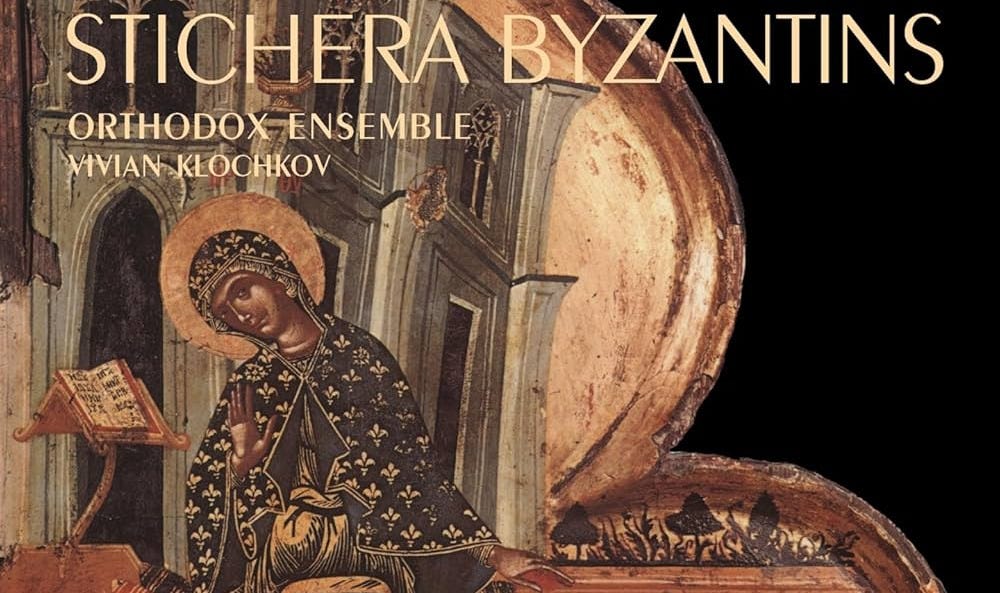

Elsewhere, we can see with regularity that στίχος is used by the Septuagint translators solely to render the Hebrew ṭûr טור. This is the case where the Book of Exodus is describing the proper setting of the stones in the breastplate of the priestly garments (Exo 28:15-21; 39:8-14); and also where the First Book of Kings is describing the construction of Solomon’s palace (1Ki 7:3,12) and the Temple (1Ki 6:36, 7:18). The former case can be considered an approbative use and the latter a pejorative use of the term. Exodus is outlining the proper worship of God among the people in the desert; whereas 1 Kings is giving a postmortem of the kingdom’s downward march into the pits of idolatry and self-aggrandising rebellion against God.

Why do I mention the construction of the Temple here? Well, this is one particular place where the excellent and peerless Holy Father of the Western Church, Saint Eusebios Sōphronios Hierōnymos (or Jerome) of Stridon, uses the Latin term ordo in his Vulgate translation of the Hebrew Scriptures. Elsewhere, Saint Jerome uses ordo negatively (Job 10:22), or else as part of a complex construction which does not find a direct parallel in the Hebrew text (Neh 11:23; 2Ch 5:11).

This Latin word was at the centre of a spat on the-Social-Media-Platform-Formerly-Known-as-Twitter, between the sitting Vice-President and a former Conservative British MP representing a riding in Cumbria in northwest England. The Vice-President propounded the philosophical idea, common to late-antique Aristotelian and medieval Chinese lixue 理学 ethics, that there is a hierarchy of loves in which the closest circle of affection—the family—takes precedence over concentrically more-distant circles (neighbourhood, community, nation, world). The former Conservative MP then responded (quite correctly, as it happens) that this is an idea of pagan provenance rather than Christian. As so often happens on the Social-Media-Platform-Formerly-Known-as-Twitter, the ‘conversation’ (if it may be thus over-generously characterised) quickly descended into personal insults and speculations about the IQ of these respective politicians.

The Conservative MP happens to be correct on this point alone: the term ordo amoris simply does not appear in Scripture. It is nowhere to be found in the Vulgate; nor does any corresponding phrase like η συστοιχία της αγάπες or ṭûr ’ahabôt תור אהבות appear in either the Septuagint or the Masoretic Text; let alone in the Textus Receptus. A hierarchy of affection is not an explicit Scriptural concept. There are certainly places where it is assumed, but it is in precisely those places where it is also subjected to explicit literary critique by the authors.

But more on this later. From whence was Mr Vance articulating this notion of the ordo amoris? As it turns out, Vance was getting it, not from Scripture, but rather from Blessed Augustine—specifically, from Civitas Dei: a work of philosophy which owes far more to the pagans (and Plato in particular) than it does to Saint Paul. This same Augustine, by the way, was the one who tried to discourage Saint Jerome from translating Scripture into Latin because, in his view, the Septuagint text was sufficient and there was no need for Christians to learn Hebrew! Thanks be to God that Jerome didn’t listen to Augustine—because the Western Christian tradition of Scriptural exegesis happens to be that much richer as a result.

But, back to the principle of ordo amoris. The ‘ordering of loves’ from nearest-and-strongest to furthest-and-weakest was indeed a staple teaching of Aristotle. Yet there are several places in Scripture where this ‘ordering of loves’ is deconstructed, and even attacked. Most prominently, it is so in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew:

καὶ εἰ ἀγαπᾶτε τοὺς ἀγαπῶντας ὑμᾶς ποία ὑμῖν χάρις ἐστίν καὶ γὰρ οἱ ἁμαρτωλοὶ τοὺς ἀγαπῶντας αὐτοὺς ἀγαπῶσιν

If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? For even sinners love those who love them. (Luke 6:32)

καὶ ἐὰν ἀσπάσησθε τοὺς ἀδελφοὺς ὑμῶν μόνον τί περισσὸν ποιεῖτε οὐχὶ καὶ οἱ ἐθνικοὶ τὸ αὐτὸ ποιοῦσιν

And if you salute only your brethren, what more are you doing than others? Do not even the Gentiles do the same? (Matt 5:47)

And then, of course, the real kicker among the lot:

εἴ τις ἔρχεται πρός με καὶ οὐ μισεῖ τὸν πατέρα ἑαυτοῦ καὶ τὴν μητέρα καὶ τὴν γυναῖκα καὶ τὰ τέκνα καὶ τοὺς ἀδελφοὺς καὶ τὰς ἀδελφάς ἔτι τε καὶ τὴν ψυχὴν ἑαυτοῦ οὐ δύναται εἶναί μου μαθητής

If any one comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple. (Luke 14:26)

Anyone proposing a hierarchical ‘ordering of loves’ along the lines of Aristotle and Augustine is confronted and scandalised by the plain and obvious import of these lines from the Textus Receptus, precisely because they run completely against the ethical philosophy promoted by the Vice-President.

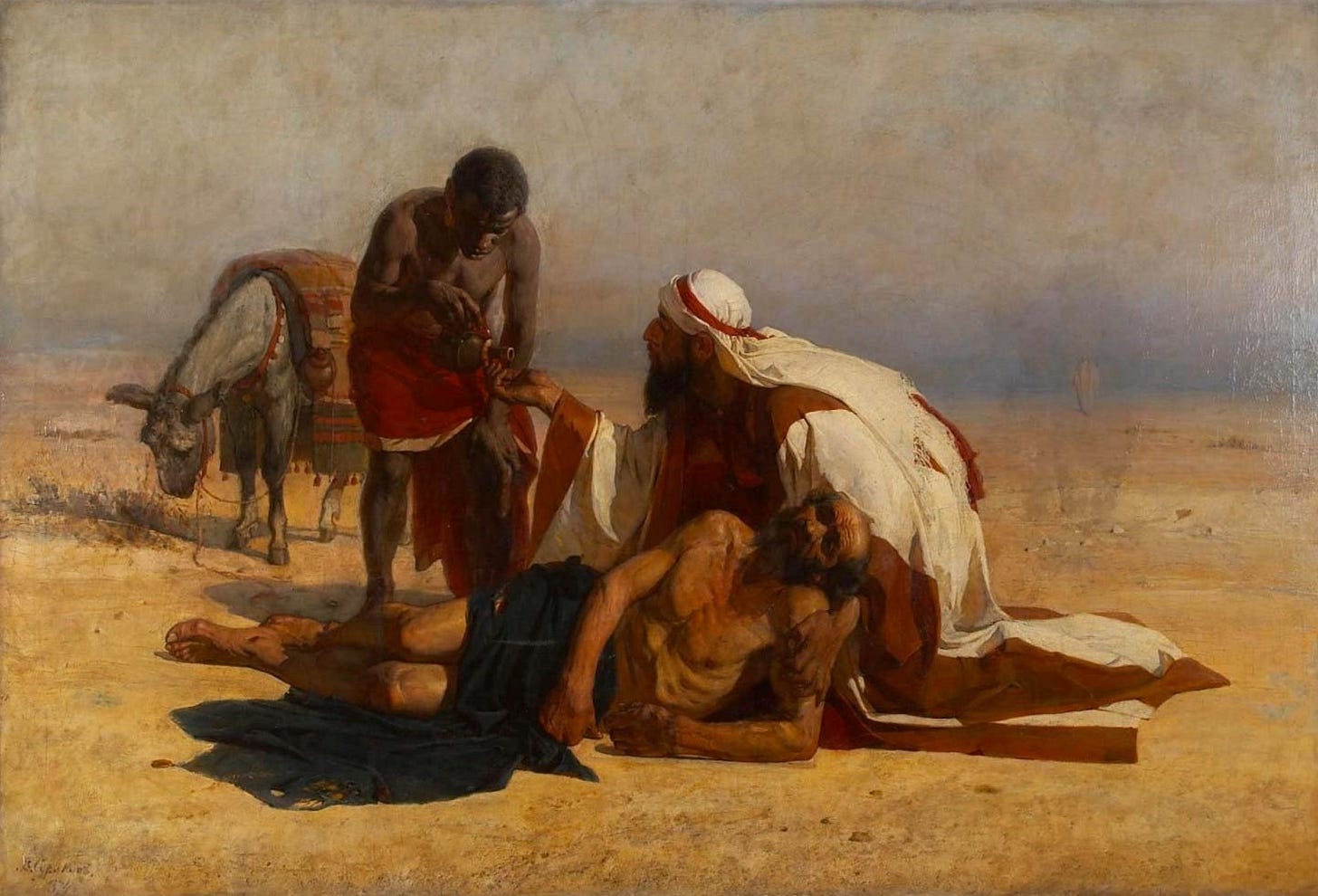

So is that to suggest that the Cumbrian former MP is right? Actually, no. In raising the implicit question of ‘who is my neighbour?’ in attempted self-justification, Mr Stewart’s pallid, cerebral universalism is also condemned in Scripture, specifically in the mašal of the merciful traveller (Luke 10:29-37). Merely professing a bland universal affection is nothing. What matters is to love the concrete instance of the one who has been placed before you in need in the middle of the road: that is to say, the one within your immediate senses and understanding, the one who shares your circumstances. It is correct to say that the Samaritan was at a greater remove from the beaten man in terms of blood relation or national belonging than the priest and the Levite who passed him by. But the Samaritan and the beaten man were still together on the road!

Even so, the commandment is correct: to love God and to love your neighbour, in that order. But there is a paradox in this formulation, because to do one without doing the other is impossible. Human beings are darkened out of this possibility. Mr Vance’s and Mr Stewart’s proposed ways to avoid this paradox both badly miss the mark, because they are trying to construct their own versions of ‘who is my neighbour?’, without reference to the commandment.

Let’s face facts. Mr Vance is literally the last person fit to lecture anyone about the amour légitime due to one’s lieu-natal. He got to where he is, exactly by betraying his roots: taking an intellectual dump all over his hometown and turning native-informant against his own people among his fellow Yale grads. And Mr Stewart? He was a literal colonial governor in Iraq, helping to loot the country for the benefit of British and American corporations. The Beltway grifter suddenly promoting love of home and hearth; and the latter-day East India Companyman professing newfound faith in universal kumbayah. And both laying claim to a God Who detests their worship of prestige and money and power! It’s not only ridiculous—it’s disgusting. Each of these men is utterly shameless: each of them precisely the wrong person to talk about the so-called ‘love’ that they respectively want to promote.

The only ṭûr ’ahabôt תור אהבות worth discussing is the one that the scholar of the law gives voice to in Luke 10:29, even if he does so for the wrong reasons. But to do so, one must submit to the text, to fall in line with the stichera of the teachings of the Torah that are thrown (ירה) at us. Any such ordo must be discussed in terms of the mašal. Otherwise, what we are doing is bending the knee to some idol. That is to say: we can choose to side with the lawgiver Moses (and St Jerome), or we can choose to side with the idolatrous Solomon (and Bl Augustine). We can line up the stones by threes and fours on the breastplate, and love the one immediately in front of us according to the command… or we can erect endless frames and rows of timber in our own intellectual palaces and fortified cities in favour of a philosophical, familial, racial, political or international ideal, against the command.

Glory be to Him alone, Who is the only lover of mankind.

سبحان الله وحده, محب القوم