The lexicography of duo 多

.... That prudence may be given to the simple, knowledge and discretion to the youth—the wise man also may hear and increase in learning, and the man of understanding acquire skill. (Prov 1:4-5)

厭浥行露、豈不夙夜、謂行多露。

Wet is the dew on the road, is it not there both morning and evening? I will allege that there is too much dew on the road.

Book of Odes, Songs of Shao and the South 召南, ‘Road Dew’ 行露 line 1.

Next up for consideration is the Chinese character duo 多. This character bears the basic English-language glosses of ‘(how) much’, ‘(how) many’, ‘more than’, ‘plenty’, ‘to increase’ or ‘in excess’. This is a staple of the first-year Chinese learner’s vocabulary, and it is also the 61st-most common character in modern written standard Chinese. It is used in a large number of vernacular compound words and idiomatic phrases, including Cantonese do-ze 多谢 ‘thank you’, duoshao 多少 ‘how many?’, chabuduo 差不多 ‘more or less’, duoduo yishan 多多益善 ‘the more, the merrier’ and zizuo duoqing 自作多情 ‘wishful thinking’.

This ideogram, duo 多, has a contested etymology. The traditional explanation, read in Shuowen jiezi and repeated in pre-modern glossaries and dictionaries up through Kangxi’s in the Qing Dynasty, reads the character as representing two ‘moons’ or ‘evenings’ (xi 夕), thus making the character originally representative of an extended period of time. Xu Shen linked this character, made up of two ‘moons’, to the similarly-pronounced character for ‘repeat’ or ‘fold’ (die 曡), originally made up of three ‘suns’ (jing 晶).

It’s a sensible and logical explication of the origins of duo. However, there is an alternate etymology, which some present-day Chinese authorities have adopted: that the duplicated ideographical element is in fact ‘meat’ (rou 肉, appearing similar to yue 月or xi 夕 ‘moon’ when used as a character component). The explanation is that meat was a delicacy enjoyed rarely by ancient Chinese; thus, their idea of ‘plenty’ would have been a surplus of meat. This explication of the character also has its logic.

I am forced to wonder if there is a connexion, at least in terms of pronunciation rather than in terms of graphical form, between the character duo 多 and the character shuo 說 (based on dui 兌 ‘to exchange’, ‘cash’, ‘to inundate’, ‘to dilute’ and supposedly pronounced /*hljod/ in Old Chinese). I am hesitant about putting this hypothesis forward because it tends to go against the grain of most modern linguistic scholarship, and because it appears to rely on a modern rhyme scheme which might fail to account for pronunciation drift. Also, because the character is a pure ideogram, we actually have very little idea of how duo 多 actually sounded in Old Chinese. Various modern reconstructions link duo 多 to the characters da 大 (‘big’), shu 庶 (‘common’, ‘ordinary’, ‘many’, ‘numerous’, ‘pertaining to a concubine or her children’) or zhu 諸 (‘each’, ‘every’, ‘all’, ‘many’, ‘widespread’).

If, however, duo 多 is a loanword from a non-Sinitic language, it may have an entirely different trajectory in written Chinese, such that a likeness and connexion to shuo 說 and dui 兌 might not be out of the question. The Kra-Dai languages of southeast Asia (Thai, Lao, Zhuang, Hlai, Kam) have a root word /*hla:ja/ which also means ‘many’ or ‘much’, which is similar in its original pronunciation to the ancient pronunciation of shuo 說 and dui 兌, and which is acknowledged by most modern linguists to be connected in some way to the lexeme duo 多… though which way the borrowing actually went is a matter of debate.

It would also mark an interesting interfunctionality between duo 多 and shuo 說, that mirrors the dual uses of the Semitic root sābā‘ שבע or sab‘a سبعة (‘seven’, ‘week’, ‘oath’, ‘plenty’, ‘fill’, ‘full’, ‘satisfy(ing)’, ‘enough’). The reference to a ‘week’ (of seven days) in this Semitic root, for example, parallels the ancient explanation of the grapheme duo 多 being made up of multiple moons and representing an extended or complete period of time. If, on the other hand, the etymology of duo as representing two pieces of meat were correct, it would indicate a cross-functionality of the meaning of ‘plenty’, as in Joseph’s prophetic interpretation of Pharaoh’s dreams in Genesis.

But I want the careful reader to notice something important.

Everything that I just did above, trying to link duo 多 to shuo 說, is speculative.

It’s zizuo duoqing 自作多情.

As Jonathan Frakes of Star Trek fame might tell you: ‘it never happened’.

Or, in the immortal, eternally-memetic words of Stephen McHattie: ‘it’s a faaaaaake!’

This is, unfortunately, what a lot of scholars, Sinologists and linguists do… including me! (So take even what I say with a grain of salt.) We rely on reconstructed pronunciations of linguistic forms that are no longer extant. Obviously we no longer have any communities of native speakers of Old Chinese around. And so we are conducting what amounts to thought-experiments. We leave the artefacts, the tangible data of the text, and we enter the accursed Aristotelian αἰθήρ, the poltergeist-palace of the Platonic forms.

Some of these thought-experiments, granted, can be better-informed than others. But they all still rely on what western scholars extrapolate about ancient forms of Chinese sounded like. These extrapolations are based on fragmentary evidence, post-Classical rime dictionaries, phonetic component comparisons, polyphonic characters (duoyinzi 多音字) and so on.

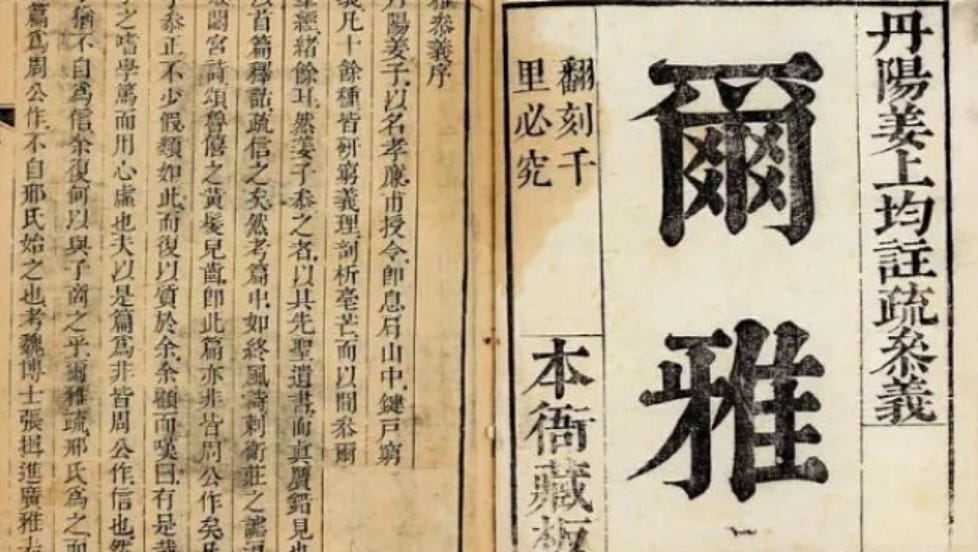

A more sensible approach, one more grounded in reality, would attempt to build a lexicography of ancient forms of Chinese based on the Classics, beginning with the Odes and the Documents… and then determining the functions and textual trajectories of each lexeme. For example, my hypothesis about duo 多 and shuo 說 amounts to a pile of nonsense… if it rests solely on a tenuous link from the pronunciation of a reconstructed proto-Kra-Dai language. But on the other hand, if we examine the Classics and Classical-era texts, and see what associations and parallel functions occur, there might be other cases or better comparisons to make. For example: there is an attested, factual linkage between duo 多, the aforementioned shu 庶, and shi 師—which can be found in the Classical-era Erya 《爾雅》. That is not speculation. That is actual data, representing an actual link.

In other Classical-era texts, we can see duo 多 appear in an adjectival or adverbial function linked to another noun or another verb. For example, in the Odes we can find phrases like duori 多日 ‘many days’; duolu 多露 ‘much dew’; duoyan 多言 ‘chatter, talk, gossip’ (also found as such in the Hanfeizi); duoyi 多益 ‘great(ly) increase’; duofu 多福 ‘many blessings’ or ‘greatly blessed’; duozang 多藏 ‘many treasures’; duoshi 多士 ‘many men’ or ‘numerous officers’ (this appears often in the Documents); duobi 多辟 ‘many regulations’. In the Daodejing we can see phrases like duoyi 多易 ‘much ease’ and duonan 多難 ‘much difficulty’ (a phrase which we also see in the Odes), and in the Art of War we can see duosuan 多算 ‘many calculations’ and duoli 多力 ‘great strength’.

The other main function of duo 多 in these Classical texts is as a verb, meaning ‘to increase’ or ‘to multiply’, or sometimes even ‘to praise’ (as in, ‘to increase’ or ‘magnify’ in one’s speech!). This is the case, for example, in duo wo gou min 多我覯痻 ‘many are the infirmities I see’ in the Ode ‘Sang Rou’ 桑柔, or er duo wei xu 而多為恤 ‘and my miseries multiply’ in the Ode ‘Di Du’ 杕杜. In the sense of ‘to praise’, that usage appears in the Hanfeizi: 「古傳天下而不足多也。」 ‘On account of this, the transmission of [the office of ruling] all under heaven was not met with praise enough.’

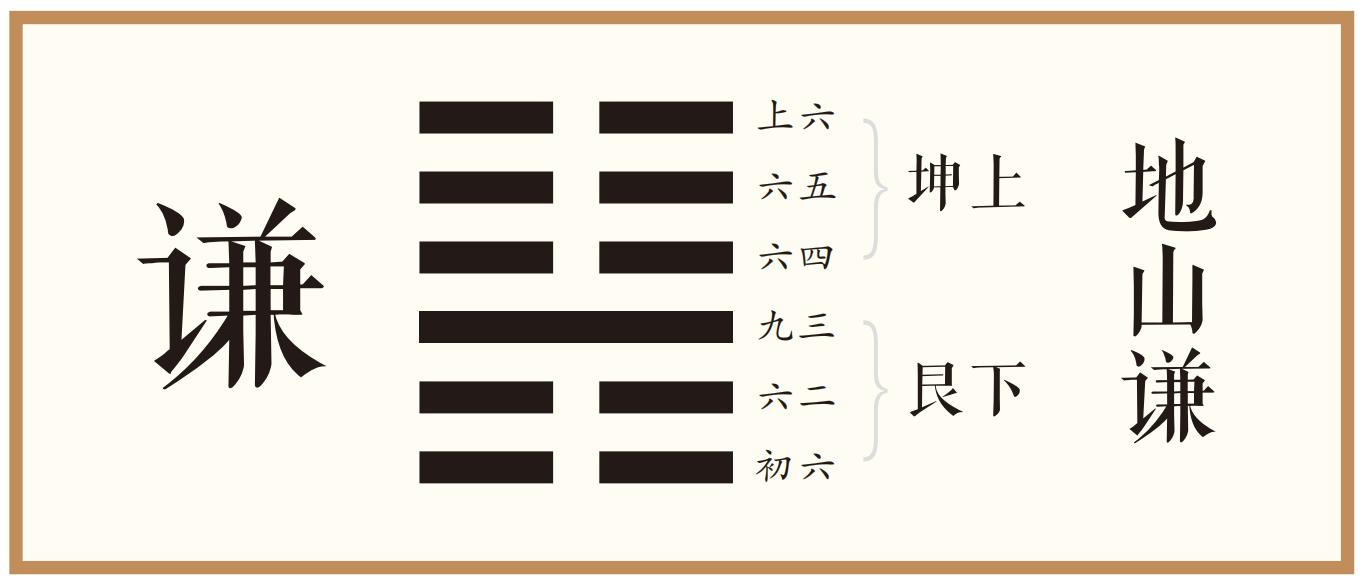

Much more rarely, duo 多 appears as a noun, meaning ‘mass (of)’, ‘majority’ or ‘excess’. One sees this usage in the Mozi: 「聖王之命也,多寡之。」 ‘The aim of the sage-kings was to reduce excesses’. This, in turn, is a paraphrase of the Book of Changes: 「君子以裒多益寡。」 ‘The superior man, in accordance with this, diminishes what is excessive (in himself), and increases where there is any defect’.

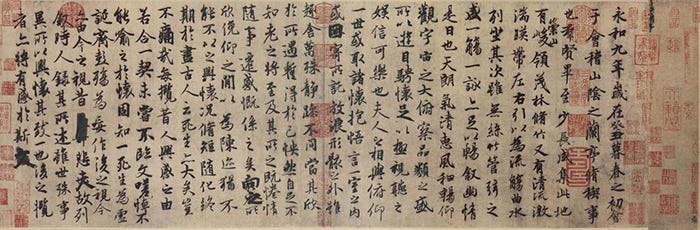

By examining the various functions wherein a very common word like duo 多 is used, it becomes easier to avoid confusion or wind up a slave to ‘motivated readings’ and mishandlings of a particular text. It also enables the texts themselves to be read with a greater depth and sensitivity. This was one reason why Confucius was so adamant about zhengming 正名 ‘the rectification of names’. He wasn’t being a linguistic prescriptivist—far from it! He was being a functionalist. He wanted his students to hear the Odes, to study them, and then to discuss them fruitfully. But in order for that to happen, they needed to be able to interface with a certain degree of confidence with the original text of the Odes themselves… lexeme by lexeme and syntax by syntax. This is why the work of early lexicographers like Bu Zixia (traditionally, the compiler of the Erya) and Xu Shen (compiler of the Shuowen jiezi) is so valuable, despite some of their limitations. They provide us with a much-needed window into how the early Chinese read their own language.

I want to reiterate that my project here is not a latter-day Sino-Babylonianism, and still less an attempt to proselytise Chinese people. Even though I happily admit that I am interested in demonstrating how West Asia and East Asia, the Levantine-Arabic and Chinese worlds, interacted over time (not just a couple of fleeting or momentary historical accidents during the Tang, Yuan and Qing Dynasties!), I’m not trying to force a connexion between the ancient Sinitic and ancient Semitic worlds where none exists. I have no interest in colonialist fantasies; only in what’s real. My suspicion is that the Chinese Classics and the West Asian Kǝtubim do in fact share a parallel purpose. Thus, I want Chinese readers to study their own Classics as literature… possibly taking the West Asian Kǝtubim as an added source of data, where and if it is relevant.