The lexicography of jian 見 and xian 現

‘The eye is the lamp of the body. So, if your eye is sound, your whole body will be full of light.’ (Matt 6:22)

The word jian 見 (simplified as 见) in Chinese is a straightforward, purely semantic ideogram with no phonetic component. It depicts an eye (mu 目) with two beams of light (er 儿) emerging from it, representing (according to the Shuowen jiezi) the perspective of the eye or the angle of vision. This is a lexeme that covers a lot of territory even from archaic Chinese, and continues to do so even today.

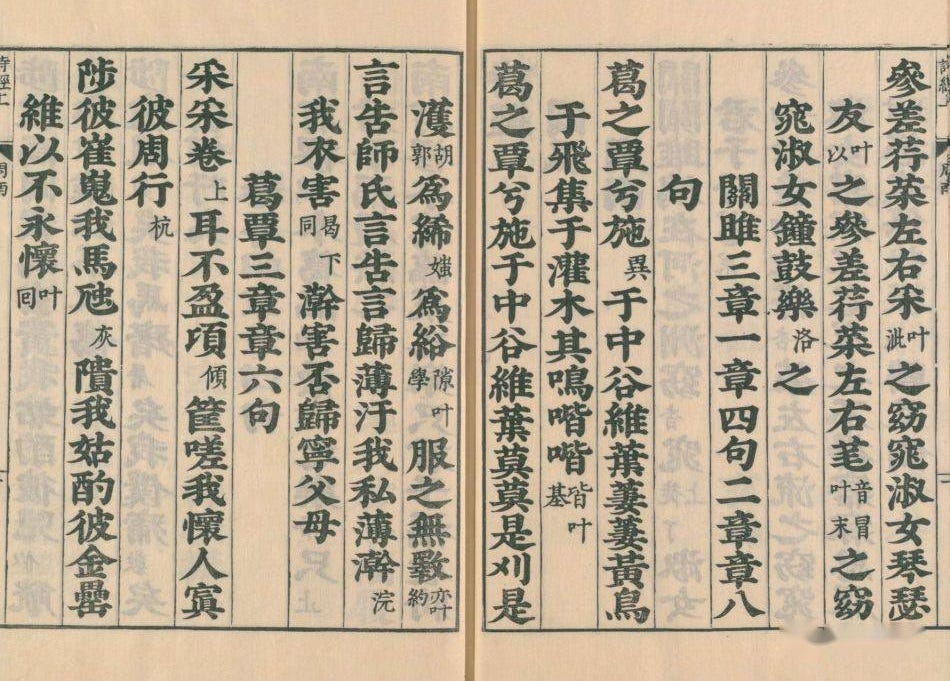

Jian 見 can mean, straightforwardly, ‘to see’ with the eyes, ‘to catch sight of’ something, ‘to observe’ or ‘to behold’, as in jiandao 见到. In this sense it is commonly used in the modern transitive verb kanjian 看见 ‘to see’, ‘to notice’ with the eyes. There are several regional and colloquial variations of this phrase: choujian 瞅见 ‘to (take a) peek at’; qiaojian 瞧见 ‘to see’; piejian 瞥见 ‘to glimpse’; mujian 目见 ‘to see for oneself’; or the Cantonese mong gin 望见 or tai gin 睇见 ‘to see, to observe’. But more generally it is also used for any kind of sensory perception. I already mentioned the common modern Chinese compound tingjian 听见 ‘to hear’, but there are also mengjian 梦见 ‘to dream (of)’, tuijian 推见 ‘to imagine, to surmise’, yuanjian 远见 ‘foresight’, jianshi 见识 ‘experience’, jianjie 见解 ‘to understand’ and cuojian 错见 ‘to misunderstand’.

The expanded sense of ‘to see’ gave jian 见 the additional gloss of ‘to meet (with)’ or ‘to come across’, as in jianmian 见面 or xiangjian 相见 ‘to meet up with’. This usage is also just as common in colloquial modern-day Mandarin as in classical Chinese. The common phrase for ‘good-bye’ is zaijian 再见: literally ‘(we’ll) meet again’. Yi huir jian 一会儿见 is ‘meet you in a bit’. And of course there’s the famous hao jiu bu jian 好久不见, ‘[it’s been] too long [since] last we met’, which was loan-translated unceremoniously into English in the early 20th century as ‘long time no see’, and used cruelly to mock various non-native English speech patterns.

The same sense of jian 见 as ‘to meet’ can also be used in figurative ways: jiancheng 见称 ‘to be met with acclaim’; jianxiao 见笑 ‘to be met with ridicule’; jianzui 见罪 ‘to be met with offence’; or even jianbei 见背 ‘to meet the ancestors’ (a euphemistic way of saying ‘to die’). In classical Chinese, jian 见 could also be used in military and historical contexts to mean, of opposing armies, ‘to meet in battle’. This sense of ‘to meet’ also gave rise to a plethora of associated glosses, including: jiejian 接见 ‘to grant an audience to’; yinjian 引见 ‘to introduce’; and canjian 参见 ‘to reference, to cite’.

The coordinate term in Semitic, is the triliteral r-’-h ר-א-ה, or r-’-y ر ء ي, which has a similar lexical range. Obviously, both the Biblical Hebrew rā’â ראה and the Arabic ra’ā راى carry the basic gloss of ‘to see’, ‘to behold’, ‘to perceive with the eyes’:

ויּרא אלהים את־האור כּי־טוב

And God saw that the light was good. (Gen 1:4)

However, in both Biblical Hebrew and Arabic, the same root ‘to see’ doubles as its own stative form, so that the same verb can mean ‘to see’ or ‘to be seen’. Likewise, in classical Chinese, jian 見 also means ‘to appear’, ‘to manifest’ or ‘to be evident’! See, for example, the Classic of Rites, describing what happens in nature in the last month of spring:

桐始華,田鼠化為鴽,虹始見,萍始生。

The Elaeococca [kalo nut tree] begins to flower. Moles are transformed into quails. Rainbows begin to appear. Duckweed begins to grow.

Book of Rites《禮記》, 6.21

In modern Chinese, this stative sense of ‘to be seen’ has been clarified in post-classical Chinese with the ‘jade’ radical, so that it has become xian 現 (simplified 现), as in chengxian 呈现 or xianxian 显现 ‘to appear, to show’; xianzai 现在 ‘now’; xianchu 现出 ‘to display, to show (off)’; Fujian dialect aihian 爱现 ‘to be fond of showing off’; faxian 发现 ‘to discover’; shixian 实现 ‘to achieve, to realise, to manifest’; duixian 兑现 or xianjin 现金 ‘cash’ (as opposed to credit or cheques). The same function of jian 见 / xian 现 as ‘to show off’ or ‘to display’ is mirrored in the Arabic ri’ā’a رئاء ‘to show off’, and as ‘appear’ in the Arabic ri’yan رئياً ‘appearance’, or in Biblical Hebrew as ra’ê ראה (as in ‘let the dry land appear’ ותראה היּבּשׁה, Gen 1:9).

In North American and British English, this doesn’t quite work the same way as in the Semitic languages or as in classical Chinese, though obviously ‘to be seen’ is a valid English phrase. The closest English analogue I can think of to the stative usage of jian 見 or ra’ā راى would be the Jamaican English function of ‘seen’ to mean ‘clear’, ‘evident’, ‘understood’ or ‘to understand’.

The function of sight—seeing and being seen—of course, is a vital one in Scripture. The first One Who sees everything, of course, in the beginning, is ’Elōhīm: the same ’Elōhīm Who creates the light by which all the rest of us derive our powers of sight. God’s powers of sight, and thus of understanding, therefore circumscribe the entirety of the cosmos that He creates—in the text.

This function is critically important, because the reader approaches the text using her faculty of sight. Unfortunately, braille had not yet been invented in the fourth century BC. Though obviously a blind person can indeed read cuneiform inscriptions on clay or stone, they are at something of a disadvantage when it comes to scrolls of papyrus such as the Torah was written on. But Scripture tells us right out of the gates: God enjoys the fullness of the faculty of sight. We do not. We are no better than the blind when it comes to seeing the words that we read; and in fact we are worse than blind. Blind people simply cannot read. We who can read the papyrus, on the other hand, choose not to see what we read. Therefore, if we boast in our sight, we earn the greater condemnation (Jn 9:41).

The exegetes of the Chinese Classics do say the same things. Now, I give poor Mencius a lot of crap. That’s partly because he gives licence for lazy exegesis. But that’s also partly (and I admit I’m being unfair here) because he is so beloved by the modern ‘philosophical’ Taiwanese and Hong Kong Neo-Confucians. Here, though, I happen to agree with him (and, more importantly, St John happens to agree with him), particularly when he says—as to King Hui of Liang (Liang Hui Wang 梁惠王):

曰:「挾太山以超北海,語人曰『我不能』,是誠不能也。為長者折枝,語人曰『我不能』,是不為也,非不能也。」

[Mencius] replied, ‘In such a thing as taking Mount Tai under your arm, and leaping over the North Sea with it, if you say to people “I am not able to do it,” that is a real case of not being able. In such a matter as breaking off a branch from a tree at the order of a superior, if you say to people “I am not able to do it,” that is a case of not doing it, it is not a case of not being able to do it.’

Mencius 1.7

So, I am saying the same as what Mencius 1.7 and John 9:41 are saying: that there are cases of truly being unable (bu neng 不能) to see, and that there are cases of being unwilling (buwei 不爲) to see!

We are unable, in our current state, to see God directly. In the Old Testament, only Moses comes close to seeing God as He truly is. Even then he is only permitted to see God’s back, and not His face, because, as God Himself says: לא־יראני האדם וחי ‘no man can see Me and live’ (Ex 33:20). And we should not think we who possess the New Testament are any better, because we have Saint John to tell us that ‘no one has ever seen God’ (Jn 1:18). Our faculty of sight is limited. We should therefore take St Ignatius Brianchaninov’s advice, at least in this particular instance, and implicitly mistrust as delusional any mystical theophanies, appearances in dreams or direct revelations of God to the human senses.

What we have, rather, is the Law which is inscribed by God’s hand: that is to say, we have the text of the Torah. We also have the scroll which is placed by God upon the tongues of those He has called to speak it: that is to say, the Nǝbī’im. And we have the wisdom writings, or Kǝtubim, of the followers of God who compiled Scripture. This is a literature that is a common authority to Jews, Christians and Muslims. And this literature, even a blind person can learn to read!

But it is literature.

There are, of course, many people who attempt to read this literature as something other than literature. There are those who seek in it a historical justification for the existence of their particular institution. Or who seek to create out of it a mythological ethno-genesis. (But in fact the actual, Scriptural Bǝrešiṭ explicitly provides, not only for all ethnic groups of humans, but also for the ṭôlǝdôṭ of all the heavens and the earth! This is why, even if it were ever proven, the existence of extraterrestrials would not constitute an argument against the existence of the Scriptural God.) Or who read it as the justification of a particular pseudoscientific view. Or who read it in the service of a particular ideology. These are the wilfully blind.

This is, after all, a literature that endlessly condemns the building of monuments, towers and walls (see what happened to the city of Enoch, or the tower of Babel, or the golden calf in the desert!) and a literature that destroys even its own Temple in the end. This is a literature that constantly belittles and emasculates its own protagonists, that airs the ‘dirty laundry’ of David and his royal family in public. See how far that gets you in, say, Thailand! This is a literature that openly mocks all human pretensions to knowledge of truth, and that explicitly tells us ‘put not your trust in princes, in a son of man, in whom there is no help’ (Ps 145:2). If you put your trust in the literature, it will open your eyes and free you from the princes. But if you put your trust in the princes, they will not only castrate you (look at what happened to Sima Qian 司马迁!) but make you blind yourself to the literature, which is a far worse fate.

One of my arguments here is that the Sinitic Classics serve a purpose parallel to the Semitic Kǝtubim. The authors and compilers of the Classics were living in a time when the Zhou Dynasty’s authority was waning, and power was being usurped by violent, sadistic, unscrupulous princes and noble families. The authors and compilers of the Classics, of whom Confucius was the last, wrote out of a marked frustration with the Zhou seemingly following the self-destructive path that the Yin Dynasty before them had taken.

My interpretation, therefore, is that the canonisation of the Odes had a literary and a political-didactic purpose similar to the Psalms, with faithful lovers being linked to Tian 天, and lords and rulers in particular being likened to coquettes and philanderers. (Qu Yuan 屈原, a local poet and exiled official of the Kingdom of Chu 楚国 took this conceit a step further and likened himself to a spurned lover in his poem ‘Li Sao’ 离骚.) And the canonisation of the Documents and Rites, deliberately borrowing the authority of the ancient kings of Zhou, showed in a positive way how a ruler could potentially rule according to the will of Tian. In this way they mirror the Book of Proverbs, which similarly borrows the authority of Solomon. However, the Changes are meant to show, similar to the Book of Ecclesiastes, that all human affairs are mutable and all human purposes proscribed within the workings of Tian. And finally, the Spring and Autumn Annals serves the same purpose, using the history of the State of Lu 鲁国 as a microcosm, as the Ezra-Nehemiah-Chronicles cycle which ends the Hebrew canon. It demonstrates the futility of all purely-human endeavours, and indicts the hubris of rulers who would try to construct for themselves a perfect state.

I therefore agree with the Political Confucians, like Jiang Qing 蔣慶 and Kang Xiaoguang 康曉光, that the prophetic-religious Gongyang Commentary represents a more faithful exegesis of the Spring and Autumn than does the historiographical Zuo Commentary. Where I tend to differ from the Political Confucians going back to Kang Youwei 康有爲, is that I don’t see an optimistic, progressive world-historical telos implied at all, anywhere in the text. (I should note that not all Political Confucians share Kang Youwei’s optimism. Many are quite critical in ways I would consider healthy.)

I invite Chinese inquirers into the Semitic and Greek Scriptures, to study the languages of Scripture—Hebrew, Greek or Latin—and simultaneously to study their own Scriptures, the Chinese Classics, and continue this work of lexicographical comparison. Do not become wilfully blind. Do not subject yourselves to colonialist, imperialist teachers who themselves do not know the Scriptures which they gave to you. Come, on an equal basis with me, and let us study together! Come, and let us see (Jn 1:39)!