The lexicography of jing 經

‘And the tables were the work of God, and the writing was the writing of God, graven upon the tables.’ (Ex 32:16)

In this Chinese lexicography series entry, I am happy to approach the word that glosses ‘Classic’ in English… and also the Bible. I am speaking, of course, of the Sinitic word jing 經 (simplified 经).

Actually, jing 經 is quite a nimble little lexeme, as one might reasonably expect of the 62nd most common character in written Chinese. It consists of a silk radical (mi 糸, a ‘thin strand of silk’) or semantic element, linked to the phonetically-allied character jing 巠, which refers to streams of water, particularly those which flow underground or that feed the water table. Jing 經 is a lexeme that, according to Han Dynasty lexicographer Xu Shen, has to do with weaving (zhi 織), and specifically the ‘warp’ in a piece of woven material—the ‘streams’ or fine threads of fabric running lengthwise that hold the loomwork in place.

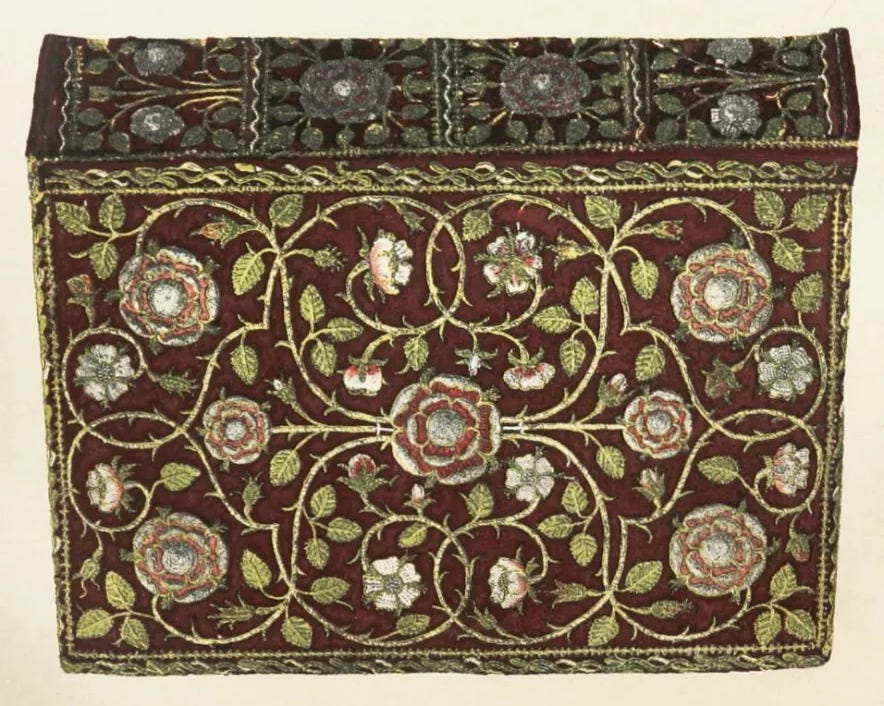

Small but important aside here. Weaving is a particularly important art for nomadic pastoralist peoples—for shepherds. This is because they live in areas where plant-based fabrics (like cotton and linen), or even animal fabrics dependent on agriculture (such as silk), are not readily available except by trade, and so they have to use the wool of sheep to clothe themselves. For the (historically) nomadic-pastoralist Diné, or Navajo, people of the American Southwest, weaving is more than just an art. It is sacred. It embodies their creation stories, their prayers and their ceremonies.

But because weaving is a sacred art, and because its creation is so bound up with the way of beauty (hózhó) which they honour, among the Diné it is considered gauche if not outright rude to offer an explanation or a narrative for another weaver’s art. (Yet naturally, this is an endemic practice among philosophical colonialist Anglos who can’t seem to resist making up stories and narratives at Indigenous peoples’ expense… such as ‘a land without a people’. This is one reason why the work of Debbie Reese, a member of the Nambé nation who runs the American Indians in Children’s Literature project, is so important.)

Getting back to the term jing 經, though: similarly to the characters dao 道 and fa 法, jing suffered a rather strong degree of lexical drift and expansion during the Classical era. It came to carry the gloss of something that ‘passes through’, just as warp runs through a material; it also came to function (in the context of medicine and anatomy) as ‘blood vessel’—the channels or streams through which blood flows under the skin (connecting here to the other jing 坙). It also came to gloss a key element or common thread which holds something together: a ‘main’ or a ‘constant’. Through this it accrued the glosses of ‘to govern’, ‘to manage’, ‘to command’—as seen in the Erya’s linkage of jing 經 with ji 基 ‘(military) base’. It also came to mean—as the ‘common thread’ of a particular school of interpretation or hermeneutics—a ‘classic text’. We know that it has this gloss in Classical-era Chinese already from the Erya, which links jing to dian 典 ‘ancient text’.

So, just as in classical Chinese we frequently see the compound word jingying 经营 ‘to run, to plan, to operate’, in modern Chinese we have compound words like yijing 已经 ‘already’; jingchang 经常 ‘frequently’; jingguo 经过 ‘to pass (through)’; jingji 经济 ‘economy’ or ‘economic’ (through the sense of ‘to manage’); jingmai 经脉 ‘blood vessels and meridian lines’ (in Chinese medicine); jingshi 经世 ‘national governance’; jingwei 经纬 ‘warp and woof’, ‘longitude and latitude’; yuejing 月经 ‘menses’, ‘menstruation’; zhengjing 政经 ‘political economy’… as well as the names of the various texts studied and exegeted (jingjie 经解) by the various schools of thought in ancient China. The Book of Odes is the Shijing 《詩經》; the Book of Changes is the Yijing 《已經》. Naturally there is also the Daodejing 《道德經》 and the Classic of Law or Fajing 《法經》.

Holy texts of other schools are referred to also as jing: the Tripiṭakas are called Zangjing 《藏經》; the Bible is the Shengjing 《聖經》; the Qur’ān is the Kelanjing 《可蘭經》. Other texts which are not considered holy texts were also later, perhaps in some cases tongue-in-cheek, called jing, like the Confucian commentary Classic of Filial Piety or Xiaojing 《孝經》, or the entirely-secular Classic of Tea or Chajing 《茶經》.

The original sense of jing 经 meaning ‘warp’ as in a piece of weaving, is attested from the Yijing:

雲,雷,屯;君子以經綸。

(The trigram representing) clouds and (that representing) thunder form Zhun. The superior man, in accordance with this, (adjusts his measures of government) as in sorting the threads of the warp and woof.

Book of Changes 《易經》, Zhun ䷂屯 1

The term jingying 经营 is seen with some regularity in the Book of Odes—that is, the Shijing:

四牡彭彭、王事傍傍。

嘉我未老、鮮我方將。

旅力方剛、經營四方。My four horses never halt;

The king's business allows no rest.

They praise me as not yet old;

They think few like me in vigour.

While the backbone retains its strength,

I must plan and labour in all parts of the kingdom.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Bei Shan 北山之什, ‘Bei Shan’ 北山 3

We can see its use as ‘constant’, in actually a negative example, in the Book of Documents, wherein Gao Yao is praising Yu’s mercy and leniency in cases where guilt is unclear:

皋陶曰:「帝德罔愆,臨下以簡,御眾以寬;罰弗及嗣,賞延于世。宥過無大,刑故無小;罪疑惟輕,功疑惟重;與其殺不辜,寧失不經;好生之德,洽于民心,茲用不犯于有司。」

Gao-Yao replied, ‘Your virtue, O Di, is faultless. You condescend to your ministers with a kindly ease; you preside over the multitudes with a generous forbearance. Punishments do not extend to (the criminal’s) heirs, while rewards reach to (succeeding) generations. You pardon inadvertent faults, however great, and punish purposed crimes, however small. In cases of doubtful crimes, you deal with them lightly; in cases of doubtful merit, you prefer the high estimation. Rather than put an innocent person to death, you will run the risk of irregularity and error. This life-loving virtue has penetrated the minds of the people, and this is why they do not render themselves liable to be punished by your officers.’

Book of Documents 《尚書》, Counsels of the Great Yu 大禹謨 11

Intriguingly, the well-known and versatile Semitic root k-t-b כ-ת-ב or ك ت ب traces itself (pun very much intended) through a similar trajectory. This triliteral k-t-b originally connoted forming a line or etching a line into a rock, or digging a trench in the earth (see the resemblance to jing 坙 here?). There is an Akkadian term takāpum ‘to pierce’, which uses the same consonants in a different order (metathesis), showing a familial similarity. But it can also be used to mean ‘to stitch’ or ‘to sew together’, as seen in ar-Rāghib al-Iṣfahānī’s 12th-century Qur’ānic exegetical work Mufradāt alfāẓ al-Qur’ān! The kitāb was therefore both the seam created when a furrow was dug into the ground and also the hem created when two pieces of cloth or hide were sewn together. One can see from this how k-t-b acquires both the functions ‘to write’ (to join characters together), and also ‘to decree’, ‘to enact’, ‘to ordain’ or ‘to register’—and note how jing 經 acquired similar functions, such as jingying 经营 and jingji 经济!

In Hebrew, also, the root k-t-b connotes etching. The tablets of the Law were engraved by the hand of God. Elsewhere—such as in 2 Chronicles 35:4—the Hebrew kǝtāb כתב connotes the enrolment or registration of men into a military division, paralleling the Arabic use of katībah كتيبة ‘battalion’. The usage of kǝtāb in referring to royal decrees, edicts or written instructions also attests a connotation of command, of authority.

The Semitic kǝtāb, therefore, is supposed to be placed above the ego of the human who is reading it. It is placed as an authority to which one is held accountable and which one must obey. This is in contradistinction to practically all of Western theology, which (in different ways) elevates the human ego above the kǝtāb. We Orthodox, unfortunately, subscribe to an idea that our institution, the Church as a whole, is above the kǝtāb, being supposedly the same structure that produced the kǝtāb. Catholics subscribe, unfortunately, to an idea that the Supreme Bishop of the Church is above the kǝtāb… hence, the Papal magisterium. And Protestants continue to subscribe, unfortunately, to the notion that every single reader of Scripture is above the kǝtāb, even as they pretend to be setting the kǝtāb in the position of the greatest importance!

What is worse—we Westerns lord our egoistic rationality over the Semites who still attempt to bend their own egos to the authority of the kǝtāb. Historically, this has meant claiming (as Origen, Augustine, Tertullian and others in the Early Church did—and too many followed their lead) that Jews were inferior, that they were hidebound and literalistic in their orientation to the Old Testament. Nowadays, the same antisemitic tropes play into negative stereotypes about Muslims. This is true even among politically-liberal Catholics who accuse Muslims of ‘bibliolatry’ (often as part-and-parcel of polemical screeds against rival Christians)… all while Muslims and Christians alike are being bombed to smithereens by American weapons, placed in genocidal Israeli hands in unlimited quantity by a liberal Catholic president.

The classical Chinese mindset is far closer, as we can see from the lexical trajectory of jing 經, to the Semitic mindset than it is to our egoist-rationalist Western one. The jing 經 is a text that, like the ‘warp’ in a piece of fabric or like the underground streams that feed aquifers, is set above the reader in order to jingying 经营, or govern, the reader’s behaviour. One could not claim to be a Ru 儒, unless one was not only versant in the Six (later Five) Classics, but also took them as his reference for his thought and action, his zhixing 知行. Likewise, one cannot claim to be a Daoist unless her references are to the Daodejing, the Zhuangzi, and the commentaries based on those two texts. A classical Ru or Daoist would easily be able to understand the Muslim who submits to her text… and subsequently behaves with modesty, hospitality and generosity.

I leave it to the reader to imagine how they would view a modern American Christian, who claims Christ as Lord but then votes for either Kamala Harris or Donald Trump.