The lexicography of fa 法

There shall be one law for the native and for the stranger who sojourns among you (Ex 12:49)

乃命大史守典奉法,司天日月星辰之行,宿離不貸,毋失經紀,以初為常。

He also orders the Grand Recorder to guard the statutes and maintain the laws, and (especially) to observe the motions in the heavens of the sun and moon, and of the zodiacal stars in which the conjunctions of these bodies take place, so that there should be no error as to where they rest and what they pass over; that there should be no failure in the record of all these things, according to the regular practice of early times.

The Record of Rites 6.4

The question of law, or fa 法, was of great importance to Chinese Classical thought.

The character itself has an interesting provenance, and of course there are multiple interpretations. Its most archaic form, found in bronze and seal-script inscriptions, is actually fa 灋. This ideogrammatic compound was made up of a stream of water (shui 水), with a deer-like (lu 鹿) animal (zhi 豸, or zhi 廌)—possibly an antelope or a mythical xiezhi 獬廌—leaving or walking (qu 去) alongside.

The semantic zhi 廌 component is fairly straightforward. The xiezhi, an antelope- or goat-like animal, was presumed in distant antiquity to have the power to determine the guilt or innocence of a defendant at trial. The minister of law for the mythical Sage-King Shun 帝舜, Gao Yao 皋陶, was said to have employed a xiezhi for just this purpose. The idea was that if a person was guilty, the xiezhi would charge and ram him with his horn; if he was innocent, the xiezhi would leave him be. (Getting behind some of the mythical treatment in these stories, one imagines it might have been something like a precursor of the polygraph test, where the animal could be sensitive to the mood or nervous state of the person in front of them, and react accordingly.)

The explanation for the qu 去 component is a bit more contentious. Some authorities regard it as an abridgement of he 盍, used as a phonetic indicator (both fa 法 and he 盍 in Old Chinese may have been pronounced similarly to the modern British English word ‘gob’). Others try to link it semantically to the zhi 廌. Originally, qu 去 had the connotation of ‘to put down, to put away, to get rid of’. Potential cognate words to qu 去 in other Sinitic languages (such as Tibetan སྐྱག skyag ‘to lay down, to defecate’ and རྐྱག rkyag ‘dung, excrement’), have led some linguists to scatologically propose (with perhaps their tongues firmly wedged in their cheeks) that the ideogram qu 去 represents a man (shi 士) opening his ‘mouth underneath’, or anus (kou 口) to take a bowel movement. By extension, the inclusion of the qu 去 visual element in the ideogram fa 灋 could be a visual reference to the xiezhi ‘putting down’ or ‘knocking down’ the guilty party as part of the trial procedure mentioned above.

But fa 法, referring to the procedure of settling disputes and enforcing justice, and later to the written jurisprudence thus established, quickly took on much broader connotations in Chinese thought. The standardisation of regulations and punishments under the early Zhou (1046 – 256 BC) dynasts led to the term fa 法 gaining the additional, more abstract connotations of ‘standard’, ‘system’ or ‘method(ology)’.

In the late Zhou Dynasty, figures such as the engineer Li Kui 李悝 and the statesmen Shen Buhai 申不害 and Shang Yang 商鞅, began to develop the opinion that a society must have a unified set of legal standards in order to be just and functional. Li Kui in particular wrote an entire Classic of Law (Fajing, 法经) detailing his ideals of jurisprudence. These figures influenced a certain legal scholar named Han Fei 韩非, who envisioned a society completely governed by considerations of merit, a society of pure efficiency in which the bureaucracy could function regardless of the character of the holder of office. (It is common, indeed almost a cliché at this point, to read analyses linking the Legal School to various ‘authoritarian’ ideologies. But one can read rather from his works, that Han Fei was actually something of a spiritual precursor of the ‘expertise’-driven bureaucracy and neoliberal proceduralism of the West, as heralded by, for example, Max Weber and John Rawls.) Han Fei’s school, based on Li Kui’s Classic of Law, became known as the Fajia 法家 or the Legal School.

In the waning years of the Zhou Dynasty, the Legal School of Han Fei was the primary rival to the Ritual School (Rujia 儒家) to which Confucius belonged. Later generations would impose certain philosophical shades onto the substance of their dispute. But at root, it was because the two schools studied different texts. They had different references. The Ritual School took as its reference six core canonical texts: the Odes, the Documents, the Rites, the Music, the Changes and the Spring and Autumn Annals. (The Classic of Music is no longer extant.) Han Fei saw no value in these dusty old books. As far as he was concerned, they were at best a distraction, and at worst a vehicle for promoting unqualified people to government positions they were not suited for.

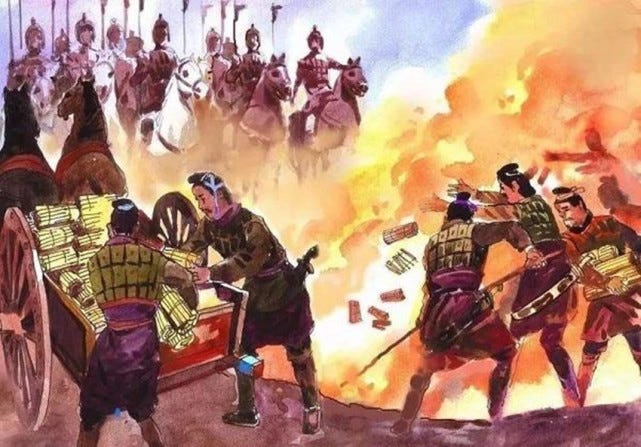

The Fajia 法家 followers of Han Fei, particularly Li Si 李斯, gained high government offices in the late-Zhou State of Qin 秦国, where they gained an enthusiastic student in the figure of a certain prince named Ying Zheng 嬴政, who became the king of the State of Qin, and later united all of the Central States (Zhongguo 中国) into the Empire of Qin (221 BC – 206 BC)… or China. The closest historical analogy to Ying Zheng in the West is probably Alexander the Great, who lived about a hundred years before him. Under the influence of Legal School ministers, in 213 BC Ying Zheng undertook a massive campaign to, as later historians would characterise it, ‘burn the books and bury the scholars’ (fen shu keng ru 焚书坑儒): that is, to wipe out the Ritual School and to destroy the traditional texts venerated by them, with private copies of the Classic of Odes and the Classic of Documents being particularly singled out for destruction. It was an act of wanton and catastrophic cultural devastation on par with Alexander’s burning of Persepolis, and this event is probably what caused the loss of all copies of the Classic of Music. As a result, Ying Zheng wound up being (rather justly) hated by the later generations of Ritual scholars whose thought later congealed into the philosophy of Confucianism, and the Legal School and its associated texts ended up being officially stigmatised… but never wholly forgotten.

The term fa 法 took on additional functions, however, during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), which is when Buddhism was first introduced to China. Early Chinese Buddhists were quick to latch onto fa 法 as an analogy for the Indian philosophical concept of dharma. Dharma, of course, refers not only to the particular duties, social obligations and strictures that pertained (differently) to each caste from the Brahmins down to the Dalits under the system imposed by the Vedic invaders from the northwest… but also came to pertain to the supposed grand order of the cosmos which mirrored and therefore justified the rigidly-stratified Hindu social system. (This is one evident reason why Hindu philosophy is so popular among our modern silver-spoon Brahmin caste in the West—academics and pop philosophers such as David Bentley Hart and his brothers, for example.)

Buddhism, of course, was a partial (but by no means a thoroughgoing) rejection and repudiation of the traditional caste system. However, it maintained the philosophical credence in a grand cosmic dharma. In fact, it had to do so, because Siddhartha Gautama himself presented his teaching on suffering (and how to extinguish suffering by extinguishing egoistic desire) as a more harmonious representation of that same dharma: a better, truer, more accurate representation of the reality of things. The Central Asians who brought Buddhism into the Central States with them found in the character fa 法, with its preexisting functions, a reasonable analogy for the Vedic dharma; and they used the former as a gloss for the latter.

So, to sum up: after Chinese exposure to Buddhism, fa 法 became associated not only with ‘law’; not only with ‘standard’, ‘system’ and ‘method’ as with Mozi and Han Fei; but even, as a Buddhist theological term, with much broader and further abstracted concepts like ‘truth’, ‘reality’ and ‘first principles’. Rather a spectacular lexical trajectory for an ideogram showing an antelope headbutting some ne’er-do-well schmuck into a river, no?

This is one more illustration of how a commonly-used Chinese character has suffered functional drift, as a result of being tasked with accommodating a broader and broader range of glosses, with philosophical and theological demands resulting in some of the more grotesque enlargements. As I mentioned in my lexicography of ting 聽, the term dao 道, for example, originated as an irreducibly feminine term which referred in antiquity to the ‘birth canal’, and de 德 to the process of ‘giving birth’. The notion of daode 道德, therefore, meant the awareness that one is born from a womb. Its usage was direct, simple and intuitive. Only later mishandling by philosophers and theologians caused dao 道 to be burdened down with an enormous and diffuse storm of glosses such as ‘way’, ‘path’, ‘method’, ‘principle’, ‘word’, ‘to say’, ‘doctrine’…

~~~

The Assyrian Christian monks who came to China during the Tang Dynasty used the lexical construct Xusuo 序娑 or Xusuofa 序娑法 to transliterate into Chinese haŠem השם: the Name of the Lord, the Tetragrammaton (יהוה).

It is deeply unclear why they used Xusuofa for this purpose. A hearer who understands modern Chinese might notice a pun with shuofa 说法 ‘phrasing, wording, explication’, in which case the Name takes on the semantic gloss, something like ‘the method of word ordering’ in Middle Chinese. But the use of suo 娑 in other religious (Buddhist) contexts for transliteration suggests a more straightforwardly phonetic use, and the Assyrian Christians who brought Christianity to China were not averse to phonetic transliterations elsewhere (for instance, they didn’t only translate ’Elāhā ܐܠܗܐ as Tianzun 天尊; they also transliterated to Eluohe 阿罗诃). The problem is that there is no straightforwardly plausible connexion between the syllable sā represented by suo 娑 in Middle Chinese, and any possible pronunciation of the Name. This led the Japanese scholars, such as Saeki Yoshiro, who studied the Xu ting Mishisuo jing to suggest that perhaps Bishop Aluoben made a typographical or a transcription error, substituting suo 娑 for po 婆.

It’s wholly possible that this was, as Saeki suggests, an error. It’s also possible that the character was deliberately miswritten in order to uphold the same taboo on speaking the Name unworthily, that prevented the Masoretes from pointing the vowels of the Tetragrammaton (though the Masoretes were clearly happy to commit the blasphemy of stamping their preferred vowels on everything else in their text). This does not require a significant stretch of the imagination. Contemporary Chinese society very clearly understood naming taboos: writing the personal name of the reigning Emperor was usually forbidden.

It’s intriguing also to consider the beautiful possibility, that Bishop Aluoben and the other monks who authored the Assyrian Christian texts in Chinese, understood the semantics of their chosen phrasing. The Yahweh of Scripture (most likely not His actual name, so I’m probably safe there) is the One Who orders the [mountains to] dance (xu suo 序娑) and Who ordains the Law (xu fa 序法). What could be more appropriate than that?