The lexicography of shao 少

And he blesses them, and they multiply exceedingly, and he diminishes not the number of their cattle. (Ps 106:38)

The character which is the antonym of duo 多 (‘many’, a character related and allied in classical Chinese to shi 師) in both classical and modern Chinese, is shao 少—a Chinese ideogram which means ‘few’, ‘less’, ‘little’ or ‘young’. Shao is, however, quite a bit less common than duo, being the 233rd most common character in the modern written Chinese language.

Shao 少 is derived from an oracle-bone ideogram which resembles four dots, or possibly grains of sand. (This is perhaps how the word sha 沙 ‘sand’ is derived). However, Xu Shen in the Shuowen jiezi links shao 少 to the similarly-shaped character xiao 小 ‘small’, with the addition of a pie 丿 (a single sideways slanted stroke) to indicate the alteration of the sound. Despite its being an antonym to duo 多 and less-commonly used, shao 少 has certain specialised functions that are worth examining carefully.

In Classical-era texts, the word shao 少 commonly meant ‘few’ or ‘less’, as in the Book of Odes: gou min ji duo, shou wu bu shao 覯閔既多、受侮不少 ‘I meet with many distresses; I receive insults not a few’ (Odes of Bei 邶風, ‘Cypress Boat’ 柏舟 4). But with considerable frequency it was also used as shaozhe 少者 ‘the young’, an antonym to laozhe 老者 ‘the elderly’, in much the same way as the modern-day Chinese compound word shaonian 少年 is. It could also mean ‘junior’ (particularly when applied to titles such as shi 師), or ‘less-experienced’.

Fans of Japanese manga and anime may recognise the this loanword from Chinese as shōnen, meaning drawn or animated entertainment that is aimed at the young teen (12-18) male demographic (such as Slam Dunk, Dragon Ball, Ranma ½, Naruto, Bleach or One Piece). It is contrasted with the shōjo 少女, seinen 青年 and jōsei 女性 demographics, which are aimed at teen girls, adult men and adult women respectively. This meaning of shao 少, however, far predates manga. Look at how Zhuangzi uses it:

少者哭之,如哭其母。

And the young men wailing as if they had lost their mother.

Zhuangzi 《庄子》, Nourishing the Lord of Life 养生主 5

Or Confucius in the Analects:

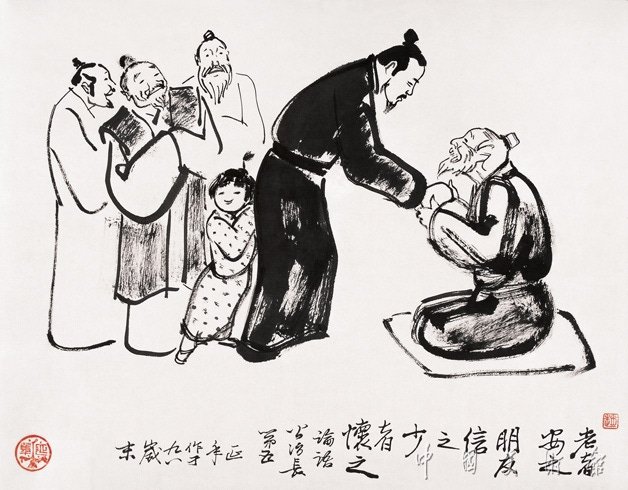

子曰:「老者安之,朋友信之,少者怀之。」

The Master said, ‘They are, in regard to the aged, to give them rest; in regard to friends, to show them sincerity; in regard to the young, to treat them tenderly.’

Analects 《論語》 5.26

However, for the purposes of students of Chinese Classics (and for ours!) there is another important compound word in which the character shao 少 appears: shaolao 少牢. This refers to a ‘lesser sacrifice’ in official rituals, in which a male ram and a boar are slain. (In the ‘greater sacrifice’ or dalao 大牢, three animals are indicated—a ram, a boar and a bull.) For this usage I refer to the Book of Rites:

天子社稷皆大牢,诸侯社稷皆少牢。

In sacrificing at the altars to the spirits of the land and grain, the son of Heaven used in each case a bull, a ram, and a boar; the princes, (only) a ram and a boar.

The Book of Rites 《禮記》 5.31

The Rites shows us something of a ‘progressive’ taxation system, wherein the King (the ‘son of Heaven’ or Tianzi 天子) would offer the most costly sacrifice of three animals; the regional princes the second-most costly (the shaolao 少牢 that we are considering here) of two animals; the landed gentry, a single animal; the unlanded high-born, fruits; and the common people, various grains or wild plants mixed with wild game, fowl or fish depending on the season.

But there is a striking resemblance between these sacrifices and those sacrifices which are set forth in Leviticus. Oxen, or sheep, or goats (but not swine!) were prescribed as the sacrificial animals in, for example, Leviticus 4. There is a similarly hierarchical division of the sin-offerings (haṭṭā’āt חטּאת) required of God’s people. Here is the commandment which the high priest is to observe if he sins, or if the entire people commit a sin:

אם הכּהן המּשׁיח יחטא לאשׁמת העם והקריב על חטּאתו אשׁר חטא פּר בּן־בּקר תּמים ליהוה לחטּאת׃

If it is the anointed priest who sins, thus bringing guilt on the people, then let him offer for the sin which he has committed a young bull without blemish to the LORD for a sin offering. (Lev 4:3)

But if it is a single leader or ruler who is responsible, then the offering of a lesser animal is required. In this case, that animal is a goat.

אשׁר נשׂיא יחטא ועשׂה אחת מכּל־מצות יהוה אלהיו אשׁר לא־תעשׂינה בּשׁגגה ואשׁם׃

או־ הודע אליו חטּאתו אשׁר חטא בּהּ והביא את־קרבּנו שׂעיר עזּים זכר תּמים׃When a ruler sins, doing unwittingly any one of all the things which the LORD his God has commanded not to be done, and is guilty, if the sin which he has committed is made known to him, he shall bring as his offering a goat, a male without blemish… (Lev 4:22-23)

Now, a lot of modern-day English-language commentary on Leviticus has a certain problem. I have not seen this problem paralleled in Chinese commentary on the Rites. And actually, I’m not entirely sure that it’s the fault of the commentary itself, though the commentary is always and everywhere a reflection on the audience it addresses.

We ‘enlightened’ whites of the modern West—it doesn’t matter if we are theologically ‘liberal’ or ‘conservative’—tend to cringe at the idea of animal sacrifice. We find it distasteful, primitive, barbaric. We think it is violent. We’re embarrassed by it. Whether it’s the Presbyterian professor Peter Leithart trying to say that we ‘evolved’ out of such a ‘barbaric’ practice, or my Anabaptist neighbour Greg Boyd trying to say that God was getting down to the Israelites’ level to prevent them from pagan worship, there is a certain degree of palpable embarrassment that accompanies Levitical exegesis in the West. We don’t like to be associated with such messy, gory, life-ending rituals, even when they are a part of our holy texts.

But it’s always worth digging deeper into the text itself whenever such embarrassment surfaces. The task of simply living outside of Eden requires the sacrifice of other life. That’s just the reality. It holds true even if you’re vegan or even if you eat only locally-sourced organic food. (Or do you somehow imagine your fruit and veggies which grow in monoculture plantations in California or in Latin America come without exploitation of human labour, or without displacement of native species?) All forms of agriculture, aquaculture and pastoralism are violence, and there is simply no pure mode of human life that does not necessitate sacrificial death elsewhere.

Indigenous people who follow shamanic or animistic religions, like the Ainu of the northern Pacific Islands, or the Evenki (Ewenke 鄂溫克) of northeastern China and Siberia, or the Dakota people of the American Plains, understand and acknowledge this reality in a direct and unmediated way. The Ainu, for example, leave sacrificial offerings (wine, carvings, utensils) to the kamuy of the animals in the places where they hunt, as thanks to the deer or the fish that they eat, that help them to stay alive. The Ewenki do the same thing when they go on hunts, as do the Nanai people to whom they are related. The Dakota and the allied people of the Oceti Sakowin Oyate here in Minnesota give thanks to the bison for giving its life to sustain them. I recently heard a tale from a Palestinian Christian family, that when they have to kill a chicken to eat, the elderly patriarch of that family will have them thank the chicken before saying grace to God and eating it. It’s the same principle.

And it is a principle that is reflected in Scripture. Even though in the garden, there was no need for sacrifice—God offered the humans and the animals both to partake of the plants that He provided (Gen 1:29-30). The first sacrifice of animal life, in fact the first death in Scripture, occurs after the fall, and arises out of the human necessity for clothing (Gen 3:22). We then see that Cain makes a sacrifice to God ‘of the fruits of the earth’ (Gen 4:3) and Abel of ‘the firstborn of his sheep and of his fatlings’ (Gen 4:4): both of which are eaten. Leithart actually comes close to the truth when he realises this: ‘the animal passes through death to be translated into smoke and to become food for a feast.’ Yes, that’s the point, Peter—leave it right there and say no more. Sacrifice is about food.

So let’s think about it this way. Is the ancient method of offering sacrifice to God and offering God a portion of what is eaten, any more ‘barbaric’ or distasteful than raising animals on factory farms, keeping them in mechanised stalls, pumping them full of antibiotics and growth hormones, feeding them to gigantic slaughter machines, and then mashing them together into a homogeneous product that we then consume without thanks? There’s a certain degree of hypocrisy in the modern Western stance, looking down our noses at people who have face-to-face contact with the animals they have to consume to survive. And there is absolutely something detestable about the way in which we accuse non-Westerners and immigrants for their culinary habits (real or imagined) and then making them scapegoats on that account.

The Bronze Age Mesopotamians and Bronze Age Chinese were human beings. They cared for their pet animals and livestock no less than we do. In fact, it’s arguable that they cared for their animals more than we do, because they had to be in daily contact with them, feed them, herd them, raise them from birth, care for them when they were sick.

So when one had to be killed, it was truly a sacrifice. It impacted in a real, tangible and visceral way (not merely symbolic!), both the emotions of the one giving the sacrifice, and his ability to feed himself and his family. This is far more so than for us moderns with our factory farms, who are eating animals that we never saw, which were born and grown and raised out of sight and out of mind for us. Part of the reason that the Rites prescribe that the king sacrifice three animals, that nobles sacrifice two animals of lesser value, that landed people sacrifice one animal, and that unlanded sacrifice fruits or grains instead, is that animals were the wealth and livelihood of the land. Remember the alternative etymology of duo 多 ‘plenty’, that hypothesises it as being composed of two pieces of meat! So it was also for the Mesopotamians of the Bronze Age, and their descendants who wrote Scripture.

There is another problem, though. The Rites’ prescription of the shaolao 少牢, like Leviticus’s enumeration of the sin-offerings due from the people or from rulers or from individuals, were meant to protect the poor. The poor were not supposed to offer their only means of sustenance to expiate their sins. Yet instead, the offering became something of a status-symbol in a West Asian culture based around honour and hospitality. If you could offer more for the sin-offering, it was because you were a big-shot. You had prestige. You could be magnanimous. In some cases, you could get big-shot status without having to sacrifice your own animals.

This is one of the corollaries in Nathan’s mašal to David in 2 Samuel 12. (Note that ḥattā’āṭ חטּאת in 2 Sam 12:13 can mean either the sin, or the sacrifice meant to expiate it!) Obviously, the direct analogy is for David’s seduction of Bat-šeba‘ and subsequent murder of Uriah the Hittite. But in Nathan’s mašal, the rich man’s sacrifice of the poor man’s sheep, to provide hospitality to a traveller under his own roof, shows how the Levitical Law could be abused in the sight of God to honour the man. This abuse of the Law forms the basis of Isaiah’s criticisms of Israelite sacrificial rituals (Isa 1:11-15) and his insistence that justice on behalf of widows and orphans (1:16-17) is what is pleasing to God, and not the honour and bragging-rights that come with providing the animals for sacrifice.

So it is God, in the Hebrew Scriptures, who removes that honour from man. He takes away man’s bragging rights, his prestige for offering the sacrifice. It is not man, but God Who provides (’Elōhīm yir’ê-llô, אלהים יראה־לּו, Gen 22:8) the sacrificial animal when Abraham is called to ascend Mount Marwah with Isaac. It is God Who provides, literally, ‘whatever’ (mān מן, Exo 16:15) the Hebrews need to survive in the desert, and sustains their lives with that sacrifice, regardless of how badly the Hebrews end up behaving themselves. Note that this is an Old Testament teaching. This is not a Christian innovation. This understanding that God in His mercy reaches down to man, condescends to man, without man’s need for sacrifice to appease Him—is in fact shared between Jews, Christians and Muslims.

The message of the Rites regarding sacrifices is subtler. I’m not saying that is good or bad. But the Book of Rites serves more or less the same function. I’m not referring only to the Rites’ repeated point that the duties of the poor do not include making expensive sacrifices (e.g., Rites 1.43; 2.88; 3.64; 4.172; 32.41 etc.). Rather, the denotation in chapter 6, the Yue ling 月令 section of the Rites, of the sacrificial goods that come in each season, and when and where that sacrifice is to be offered, serves to reinforce the consciousness in the mind of the classical Chinese reader that all of the items of sacrifice originally belong to Heaven (Tian 天) and not to the people. A human being can never perfectly repay Heaven for his life. Thus, all ritual sacrifice is in fact, giving back to Heaven what had always belonged to Heaven in the first place.

You can never be an offerer of dalao 大牢 in Heaven’s eyes. You will always be an offerer of shaolao 少牢—even if you’re sacrificing the best of your bulls.