The lexicography of shi 師

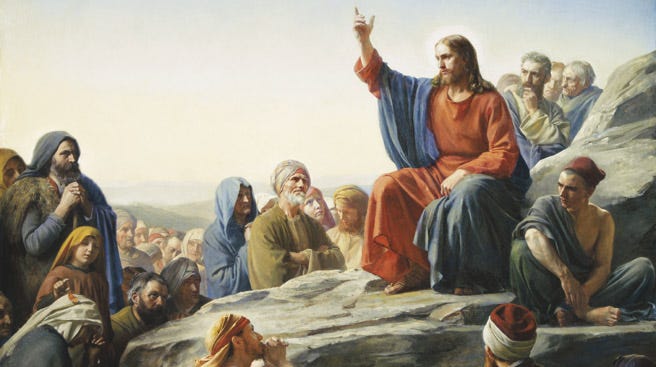

Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down his disciples came to him. And he opened his mouth and taught them. (Matt 5:1-2)

The second character of mishihe 彌師訶, Aluoben’s transliteration of the term Mǝsīḥa ܡܫܝܚܐ or ‘Messiah’, is shi 師 (simplified 师). This shi is a highly familiar character to any first-year student of Mandarin Chinese and one of the first words any student of Chinese learns, for obvious reasons. However, its lexical trajectory and full range of functionality in Classical texts may not be as well understood.

The character shi 師 is made up of a hill (dui 堆 or 垖) which is surrounded (za 帀, modern-day 匝) by people. Naturally, for any gathering of military force that large in antiquity, one needs a central rallying-point or landmark, for which a hill is eminently suited. In its original functionality, according to the Shuowen jiezi, this ideogram therefore signified a military division of 2,500 men. This usage originates from the Rites of Zhou:

五人為伍,五伍為兩,四兩為卒,五卒為旅,五旅為師,五師為軍。

Five men form a crew. Five crews form a platoon. Four platoons form a company. Five companies form a brigade. Five brigades form a division. Five divisions form an army.

Rites of Zhou 《周禮》, 2.77

In the modern-day People’s Liberation Army, shi 师 still refers to a military division—a unit smaller than a corps (jun 军) but larger than a brigade (lü 旅). For example, one of the military units stationed in Henan Province is the 11th Tank Division (Tanke Dishiyi Shi 坦克第十一师), headquartered in Queshan County. This usage of shi 師 as a ‘military division’ began to be used for the function of ‘troops’ in general, and subsequently still more generally for a ‘throng’ or a ‘mass’ of people—in Scriptural terms, an ὄχλος. This is how the term is used in the Odes:

溥彼韓城、燕師所完。

Large is the wall of [the city of] Han,

Built by the multitudes of Yan.Book of Odes, Decade of Dang 蕩之什, ‘The Grandeur of Han’ 韓奕 line 26

By extension, shi 師 also came to mean the commander of such a division. This ought to be easy for a Westerner to understand: the commander of a century of 80 men (almost 100), for example, is called a centurion. The commander of a legion is called a legate. The commander of a brigade is a brigadier(-general). The commander of a division, not quite following the pattern here, is called a major(-general). It therefore stands to reason that the commander of a shi 師 would also be called shi, and an acceptable English gloss would be ‘major’.

The usage of shi 師 to mean ‘major’ was apparently coopted very early on for civil official positions. The Classic of Documents refers, possibly to a civil office at the province level, whose holders bore the title of shi 師:

「州十有二師,外薄四海,咸建五長,各迪有功,苗頑弗即工,帝其念哉!」

‘(In appointing) in the provinces twelve Tutors, and in establishing in the regions beyond, reaching to the four seas, five Presidents. These all pursue the right path, and are meritorious; but there are still (the people of) Miao, who obstinately refuse to render their service. Think of this, O Di!’

Classic of Documents 5.4, Book of Knavery 虞書, Yi and Ji 益稷

The fact that Legge translated shi 師 here as ‘tutors’ is illustrative, though perhaps a tad anachronistic. Given that, in context, Di is being advised about matters of administration rather than of the private disposition of his household, it seems rather a stretch, in context, to think of these twelve provincial officials he appointed as ‘tutors’ rather than military commanders or border guards. I can’t be too hard on Legge, though, since he segues us quite neatly into the most common modern glosses of shi 師: ‘teacher’, ‘master’ or ‘expert’.

As I said above, shi 師 is a familiar character to any first-year student of Chinese, because they learn to address their teacher, not as ‘Mr.’ or ‘Mrs.’, but as ‘Teacher’. When I introduce myself to my Chinese students, I tell them they can call me ‘Mr. Cooper’ in English, or Guo Laoshi 郭老師 in Chinese. It is used in pedagogical functions in other contexts as well. For example, I spent a year studying Chinese at Capital Normal University 首都师范大学 in Beijing, and for two years I taught English at Baotou Teachers’ College 包头师范学院.

It’s a familiar term in popular martial-arts movies and TV shows, too, because the term shifu 師父 (or sifu) is the polite way to address one’s martial-arts master. It implies an expertise in a particular art, and the standing and skill necessary to teach that art to others. For example, in Legend of the Condor Heroes (the classic 1957 historical-fiction / martial-arts novel by Hong Kong author and publicist Louis Cha 金庸), when Guo[1] Jing 郭靖 is addressing the Six Eccentrics of the South Bank 江南六怪 who are teaching him various forms of kung fu, he calls Flying Bat Ke Zhen’e 柯鎮惡 Da Shifu 大師父; Marvellous-Handed Scholar Zhu Cong 朱聰 Er Shifu 二師父; Horse God Han Baoju 韓寶駒 San Shifu 三師父; Southern Mountain Woodsman Nan Xiren 南希仁 Si Shifu 四師父; Bustling Market Hidden Hero Quan Jinfa 全金發 Liu Shifu 六師父 and Yue Sword-Maiden Han Xiaoying 韓小瑩 Qi Shifu 七師父. (The fifth Eccentric of the South Bank Laughing Buddha Zhang Asheng 張阿生, who would have been his Wu Shifu 五師父 or ‘Fifth Teacher’, was killed in a fight with Chen Xuanfeng and Mei Chaofeng when Guo Jing was six years old.)

The usage of shi 師 to mean ‘teacher’ is likely more recent than the meaning of ‘major’ or ‘military commander’… perhaps by as much as a century or two. (As I said above, I differ from Legge’s translation of shi 師 in the Book of Documents as ‘tutors’, because it fails to be indicated by its immediate context.) The oldest Classic in which shi 師 appears as ‘teacher’ is the Book of Rites:

故聖人參於天地,并於鬼神,以治政也。處其所存,禮之序也;玩其所樂,民之治也。故天生時而地生財,人其父生而師教之:四者,君以正用之,故君者立於無過之地也。

Hence the sage forms a ternion with Heaven and Earth, and stands side by side with spiritual beings, in order to right the ordering of government. Taking his place on the ground of the principles inherent in them, he devised ceremonies in their order; calling them to the happy exercise of that in which they find pleasure, he secured the success of the government of the people. Heaven produces the seasons. Earth produces all the sources of wealth. Man is begotten by his father, and instructed by his teacher. The ruler correctly uses these four agencies, and therefore he stands in the place where there is no error.

Book of Rites 《禮記》 9.14

The Semitic root which most closely aligns with the Sinitic shi 師, and which covers a strikingly similar range of glosses, is r-b-b ר-ב-ב or ر ب ب. In Arabic, this term rabbu ربّ simply means ‘lord’, though the Qur’ān also uses it to refer to one’s stepdaughters (4:23) and to religious scholars, teachers or Jewish rabbis (3:79; 3:146; 5:44; 5:63). One has to trace this root back through the Hebrew and other Semitic languages. The familiar root from which we get rabbi can be glossed as ‘master’, ‘teacher’, ‘owner’ or ‘chief’… but it appears to be derived, very much like shi 師, from a root connoting a ‘troop’, a ‘force’ or a ‘multitude’, as in Exodus:

וגם־ערב רב עלה אתּם וצאן וּבקר מקנה כּבד מאד

A mixed multitude also went up with them, and very many cattle, both flocks and herds. (Ex 12:38)

And in Deuteronomy:

וענית ואמרתּ לפני יהוה אלהיך ארמּי אבד אבי ויּרד מצרימה ויּגר שׁם בּמתי מעט ויהי־שׁם לגוי גּדול עצוּם ורב

And you shall make response before the Lord your God, ‘A wandering Aramean was my father; and he went down into Egypt and sojourned there, few in number; and there he became a nation, great, mighty, and populous.’ (Deut 26:5)

And in Joshua:

ויּצאוּ הם וכל־מחניהם עמּם עם־רב כּחול אשׁר על־שׂפת־היּם לרב וסוּס ורכב רב־מאד

And they came out, with all their troops, a great host, in number like the sand that is upon the seashore, with very many horses and chariots. (Jos 11:4)

It appears that, similarly to the trajectory of shi 師 in later texts, the same term rab(b) רב came to be used not only for the ‘throng’, the ‘multitude’, the ‘troop’ but also its commander, the one who watches the herd, so to speak. This is particularly the case in the Kǝtubim, as the chief of the Babylonian king’s bodyguard is so indicated in Second Kings:

וּבחדשׁ החמישׁי בּשׁבעה לחדשׁ היא שׁנת תּשׁע־עשׂרה שׁנה למּלך נבכדנאצּר מלך־בּבל בּא נבוּזראדן רב־טבּחים עבד מלך־בּבל ירוּשׁלם

In the fifth month, on the seventh day of the month--which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon--Nebuzaradan, the captain of the bodyguard, a servant of the king of Babylon, came to Jerusalem. (2 Ki 25:8)

And finally, rab(b) רב comes to refer to a ‘master’, someone skilled in a useful art, just as in the wuxia novels of Jin Yong shi 師 refers to a kung-fu master. See Proverbs (though here rab is clearly used sarcastically):

רב מחולל־כּל ושׂכר כּסיל ושׂכר עברים

Like an archer who wounds everybody is he who hires a passing fool or drunkard. (Prov 26:10)

The practically identical trajectories of the terms shi 師 and rab(b) רב could very well be coincidental. But I have strong doubts about that. The more so when one considers that the reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciation for the Sinitic shi 師 prominently includes an /r/ in the initial: /*srij/. This reconstruction was built from cognate words in other Sinitic languages like Tibetan (Tibetan khri ཁྲི ‘ten thousand’) and Burmese (Myanma rai: ရဲ ‘bold’, ‘hero’, ‘rampant’, ‘police force’).

In the immortal words of Elim Garak from Deep Space Nine: ‘I believe in coincidences. Coincidences happen every day. But I don’t trust coincidences.’

Such coincidence as the convergent evolutionary paths of shi 師 and rab(b) רב fuels my suspicion that there was a shared contact and significant cultural-linguistic exchange across Asia between the Sinitic and Semitic worlds before or perhaps during the period when the Chinese Classics were being compiled.

I’m also happy to continue to assert (with my tongue perhaps not quite as deep in my cheek as before) that the Yeshua ben Yosef of Nazareth, scripturalised by Paul, was in fact a kung fu master.

[1] The similitude of my chosen transliterated Chinese surname Guo 郭 (which sounds like the first syllable of ‘Cooper’) and the surname of Louis Cha’s fictional alternate-Song Dynasty hero is completely coincidental.