The lexicography of suo 娑

The mountains skipped like rams, and the little hills like lambs. (Ps 114:4)

東門之枌、宛丘之栩。

子仲之子、婆娑其下。

穀旦于差、南方之原。

不績其麻、市也婆娑。There are the white elms at the east gate,

And the oaks on Wanqiu.

The daughter of Zizhong

Dances about under them.A good morning having been chosen

For the plain in the South,

She leaves twisting her hemp

And dances to it through the marketplace.Book of Odes 《诗经》, Odes of Chen 陈风, ‘White Elms at the East Gate’ 东门之枌

The word suo 娑 is not commonly found in classical Chinese. It is part of the compound word used here in the Book of Odes, posuo 婆娑 ‘to dance, to frolic, to saunter’, ‘to weep, to brim over with tears’ or, when used of a tree, ‘to have magnificent foliage’ or ‘to overflow with greenery’. In Fujian dialect, suo 娑 is also taken to mean a cooling sensation like that associated with the taste of mint, a chilly breeze, or a sharp sensation like being stung. Suo is associated with strong and irrepressible emotion, both positive and negative.

The double, near-contronymic connotation of this character has a Semitic bifurcation to it. It is expressive of both overwhelming joy, and also lamentation or distress. In this sense, it mirrors the double usage of the Semitic triliteral reš-qof-dalet ר-ק-ד, which connotes ‘to dance’ and ‘to leap’ for joy, but also to cause a chariot ‘to jolt’ or—as in the Psalms when applied to the mountains and hills—‘to tremble, to leap’ in awe and fear (or as if stung!) at the coming of the Lord God, as above in Psalm 114. In Arabic, too, the term raqṣ or raqaṣ رقص, derived from the same triliteral root, can mean either ‘to dance, to make dance, to play with’ or ‘to spur [a horse] to a gallop’.

But suo 娑 can also be associated with graceful movement. The phonetic component, sha 沙 ‘sand’, gives us a hint as to its original pronunciation… but it also has the, perhaps a tad romantic, association with brisk, fluid movement. Sand does not, after all, stand still! And of course, the semantic component in this grapheme is naturally a nü 女 ‘woman’. The standard Classical reference for this character is, after all, the daughter of Zizhong from the Ode of Chen, who dances under the boughs of the trees and through the marketplace with her strands of hemp. The sound and usage of posuo 婆娑 in these Odes (which are in fact Chinese folk songs from distant antiquity!) reminds one strongly of traditional Lūchūan (Okinawan) dances and folk songs, in which the syllables ‘ha-iya-sā-sā’ are repeated as a callback or an accompaniment to the moves of the dance. (It is noteworthy that the Lūchū Islands, which have an Indigenous culture that is as unique from the ‘mainland’ Japanese as it is from the Chinese, have preserved many features of traditional China even better than, say, Taiwan has.)

However, the grapheme suo 娑 came to have a much broader semantic application with the arrival of Buddhism in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), when it was used to transliterate the sounds of foreign terms, particularly Sanskrit names, into Chinese. In the postclassical period, this character was pronounced something like ‘Sal’ or ‘sigh’; as a result, it was used to transliterate the Sanskrit (or Pāli) syllable sā स. This is an interesting choice, to say the least. With few exceptions, the Chinese characters chosen for transliteration are neutral in connotation. Characters like er 爾 and mi 彌, for example, are about as close to completely lacking in emotional and rhetorical charge as one can get.

This prompts us to examine the history of the transmission and diffusion of the Buddhist religion into Chinese society. It wasn’t an instantaneous event, but a long process. As mentioned above, Buddhism was brought into China during the Han Dynasty, but at the time it wasn’t taken particularly seriously outside of foreign merchant associations and esoteric intelligentsia circles. It was a foreign creed, with outlandishly-named gods and goddesses, and a doctrine of extinction of the will that had little appeal to a Chinese mind focussed on harmonious family and community ties. For a subject of the Han, one’s social duties to one’s parents necessarily included getting married, having children and continuing the family line. Thus, Buddhist asceticism and monasticism were seen as irrelevant at best, and aberrant at worst. For the most part, if Buddhism was considered at all, it was primarily considered as a foreign form of Daoism—this is reflected in early Buddhist texts borrowing heavily from terminology derived from the Matrical School, including an identification of nirvana with the Matrical concept of wuwei 无为.

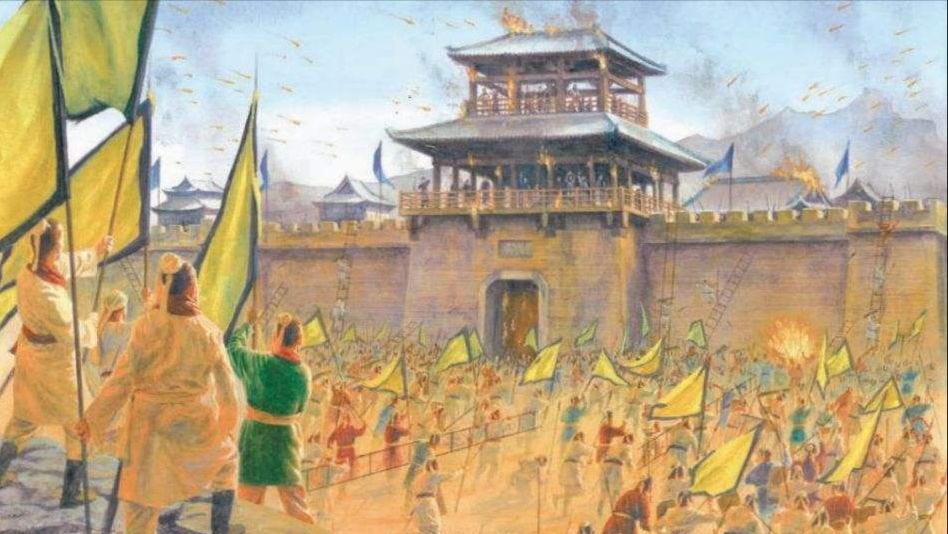

It wasn’t until the anarchic Three Kingdoms era (220 AD – 280 AD) that Buddhism began to receive a broader hearing. The Matrical School suffered a heavy blow to its credibility, in the form of a millennial movement (the Yellow Turbans) associated with the geomancer Zhang Jue 张角, that led a gruesomely sanguinary failed rebellion which laid waste to broad swathes of the Chinese countryside and killed hundreds of thousands of people. In such an environment, Buddhist preachers faced a large field of potential converts among the common people. In the Three Kingdoms and in the various foreign-ruled dynasties which followed, Buddhist temples were constructed and further attempts to translate Buddhist sutras into Chinese were made.

By the arrival of the Tang Dynasty three hundred fifty years later (618 AD), there is some evidence that there was a phonological drift. By that time the character suo 娑 may have been pronounced something like ‘shoe’. Alternatively, there may have been some confusion between the characters po 婆 and suo 娑 owing to their similarity of appearance and their use in the same Classical compound. But the character was still being used for transliteration of foreign terms into Chinese.

But the late 200s AD is when one starts to see the use of suo 娑 in transliterations of Buddhist sutras, as above, for Indic terminologies using the sound sā, as in samudra-sāgara 三母捺羅娑誐羅 ‘sea, ocean’ or śāla 娑罗 ‘teak, sal tree’. In both of these instances there is a somewhat tenuous connexion with the original meanings of ‘to dance, to leap’, ‘to weep’, or in the latter ‘a tree with grandiose foliage’, but in other cases it’s clear that the usage is purely phonetic.