The lexicology of chu 處

When the virgins were gathered together the second time, Mordecai was sitting at the king’s gate. (Est 2:19)

One of the earliest novels in China is the Shishuo xinyu 《世説新語》 or New Account of the Tales of the World, written in the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420 – 589 AD) by Liu Yiqing 劉義慶. Actually, it’s not really a ‘novel’ as such, it’s more of a compilation of biographical anecdotes and folktales collected from around China. In this compilation, appears a ‘tall tale’ associated with Zhou Chu 周處, a general of the Jin Dynasty (266 – 420 AD) which unified China after the anarchy of the Three Kingdoms era.

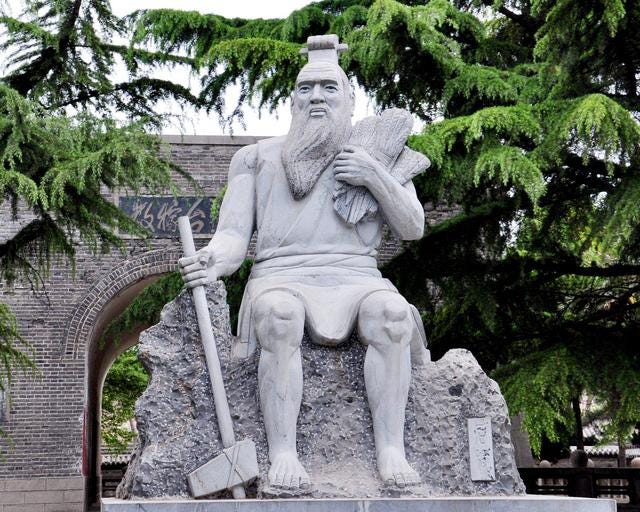

In this ‘tall tale’, called ‘Zhou Chu Eliminates Three Scourges’ 周處除三害, Zhou Chu, originally from the village of Yixing 宜兴, is portrayed as a particularly fierce, wild bandit—practically a force of nature. He hears that his home village is being plagued by three evils, and after encountering one of his fellow-villagers, he accepts the challenge of hunting down and destroying the three evils. One of them—a tiger—he manages to chase to a mountainside where he slays it. The second evil is a dragon which lives in a stream. He chases the dragon downstream all the way to Lake Tai 太湖, where he finally finishes it off. Triumphant, he brings the dragon’s head back to Yixing. As the villagers are celebrating the destruction of two of the ‘evils’, Zhou Chu comes to realise that he himself is the third evil. He leaves his village in repentance and attempts to mend his ways. The tale itself has certain Buddhist themes to it, which can readily be seen—and it was recently adapted into a gangster movie set in the modern day, The Pig, the Snake and the Pigeon, directed by Wong Ching-po and starring Ethan Juan.

Having recently done a lexicographical examination of zhi 止, the opportunity should be taken to work on this common derived lexeme, chu 處 (simplified 処 or 处)—which is the personal name of Zhou Chu. Chu is the 206th most-common character in written Chinese, and it’s something of a multipurpose. On its own in modern vernacular Chinese, it carries the function of ‘to reside’, ‘to dwell (in)’ or ‘to stay (at)’. But it is used in numerous compounds with a wide semantic range: chuli 处理 ‘to handle, to deal with, to process’; biechu 别处 ‘somewhere else’; daochu 到处 ‘everywhere’; sichu 四处 ‘all over the place’; chuyu 处于 ‘to be situated (at), to be located (at), to be in (some condition)’; haochu 好处 ‘upside, pro (side), benefit’; huaichu 坏处 ‘downside, con (side), cost’; xiangchu 相处 ‘to get along (with), to relate (to)’; chunü 处女 ‘virgin’; chufa 处罚 ‘to penalise, to punish’; chufang 處方 ‘to prescribe’; and panchu 判處 ‘to try, to sentence’.

Chu 處, as mentioned, is derived from zhi 止, which Xu Shen in the Shuowen jiezi renders as synonymous. Its oldest variant is actually chu 処, which Xu Shen interprets as a syssemantograph: it places a foot (zhi 止) under a small table or a stool (ji 几). By the time of the Zhou Dynasty, the character had been reconstituted as a phono-semantic glyph. The semantic element of zhi 止 remained, but the character hu 虎 ‘tiger’ was added as a pronunciation guide (chu rhyming with hu).

We have already seen some examples of how chu 處 is used as a verb in the Classics. For example, in the Ode ‘Grand Thunder’: 何斯違斯、莫或遑處。 ‘How was it he went away from this, not remaining a little at rest?’ And also in the Ode ‘River Branches’: 不我與、其後也處。 ‘She would not let us be with her; but afterwards she repressed [such feelings].’ And in the Book of Rites: 處其所存,禮之序也。 ‘Taking his place on the ground of the principles inherent in them, he devised ceremonies in their order.’ We can already see in these Classical references the multi-functionality of this lexeme—so much so, in fact, that it can occasionally be doubled to serve as its own nominalisation! Observe:

篤公劉、逝彼百泉、瞻彼溥原。

迺陟南岡、乃覯于京。

京師之野、于時處處、于時廬旅、于時言言、于時語語。Of generous devotion to the people was duke Liu,

He went there to [the place of] the hundred springs,

And saw [around him] the wide plain.

He ascended the ridge on the south,

And looked at a large [level] height,

A height affording space for multitudes.

Here was room to dwell in;

Here might booths be built for strangers;

Here he told out his mind;

Here he entered on deliberations.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Greater Odes of the Kingdom 大雅, Duke Liu 公劉 3

The linear connexion between chu 處 and zhi 止 mirrors the linear connexion in Semitic between the roots š-b-t ש-ב-ת or s-b-t س ب ت and y-š-b י-ש-בor w-ṯ-b و ث ب. The term šabbāt שבת ‘sabbath’ (reflected in Assyrian šapattu, Arabic as-sabt السبت and Syriac šabtā ܫܒܬܐ), is derived from the (primarily) verbal root yāšab ישב ‘to sit, to remain, to dwell’. In addition, Arabic has the term ṯabat ثبت ‘(to be) firm, fixed, stable, to withstand, proof’ which is clearly a sister term or doublet: this in turn is derived from the verbal root waṯab وثب ‘to sit, to stand, to jump’ (Syriac watab ܘܬܒ has a similar function, with most of its derivatives having to do with ‘sitting’ or ‘settling’).

What is interesting is that both the Semitic and the Sinitic roots being compared here drifted in a judicial direction. Chu 處 is used in compounds like chufa 处罚 ‘to punish’ and panchu 判处 ‘to sentence’, for example. Even in Classical-era Chinese, this function is attested: 「處大國不攻小國,處大家不篡小家。」 ‘He who rules a large state does not attack small states: he who rules a large house does not molest small houses’ (Mozi 《墨子》 7.6). The Semitic root y-š-b also has certain judicial connotations: ויהי ממּחרת ויּשׁב משׁה לשׁפּט את־העם ‘And it came to pass after the morrow that Moses sat to judge the people’ (Exo 18:13); כּי שׁמּה ישׁבוּ כסאות למשׁפּט כּסאות לבית דּויד ‘For there are set thrones for judgement’ (Psa 121:5). Even in English, actually, this function works. You can ‘settle’ an issue at law, for example, or ‘set’ a precedent, or ‘lay down’ a ruling.

What this implies is that we modern Christians tend to have a wrong idea about the Sabbath—which is precisely the wrong idea about it that nascent Judaism had. We tend to think that the Sabbath is meant for us to rest on… but the Sabbath is not, in fact, ours. It is God’s Sabbath rest. It is God Who comes and dwells (yāšab ישב) among us. It is on this occasion that God returns to His seat (Hebrew šebet שבת, Syriac mawtabā ܡܘܬܒܐ) and dispenses judgement. We sorely mistake the matter, and to our cost, if we think at that time we will be idly lounging around doing nothing. No: at that time, we are going to be instructed, and if necessary chastened, by the words the Father will speak, the proof (Arabic ṯabat ثبت) that He will present from His text, in His time of rest!

This is what Christ meant by his teaching in Mark 2:27—and how conveniently we leave off 2:28! The Sabbath was indeed made for man… for him to be instructed in the Lord’s Law! This is why the work of the weekly sabbath is first to ease the burden on foreigners, on workers and on animals (Ex 23:12), and secondly to hear the word of God read aloud (qara’ קרא), because it is a hearing (miqra’ מקרא) of the Lord who comes and sits in all of our dwellings (môšboteykēm מושבתיכם, Lev 23:3). Glory to Him alone, in Whose Law we are to be instructed.