The lexicology of ting 停 and zhi 止

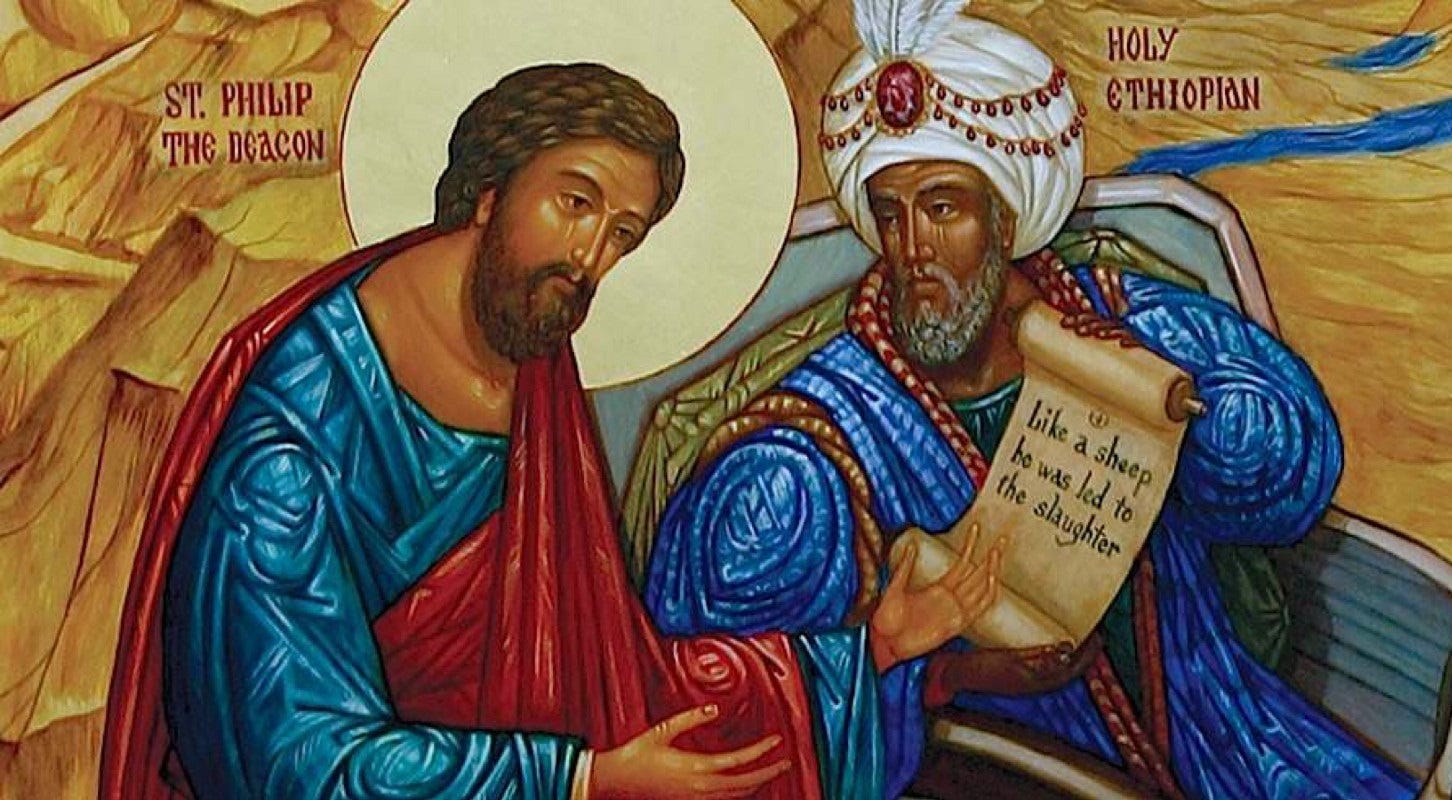

And the Spirit said to Philip, ‘Go up and join this chariot.’ (Acts 8:29)

These two characters are ubiquitous and can be found in almost any public place in China, usually as part of a common-sense admonition to the reader that something is not allowed. Jinzhi 禁止 is the word in China for ‘forbidden’ or ‘prohibited’ or simply ‘no’ (as a command), so you’ll often see public notices saying things like Jinzhi xi yan禁止吸烟 ‘No smoking’, Jinzhi paizhao 禁止拍照 ‘no photography’, or 禁止停车 Jinzhi ting che ‘No parking’.

These two characters, zhi 止 and ting 停, are practically synonyms; and since Xu Shen classified them as synonymous in the Shuowen jiezi, we may assume that they have remained synonymous for two thousand years or more. In fact, the most common vernacular Mandarin word for ‘to stop’, tingzhi 停止, is a compound of precisely these two lexemes! However, zhi 止 is found ubiquitously all over Classical-era texts, whereas ting 停 is comparatively rare there, and preferred primarily by texts belonging to the Matrical School. It’s worth examining a bit more carefully why this is.

First, the structure of each character. Zhi 止 is easier: it’s a pictogram (xiangxing 象形) of a person’s left foot. And its original function was as a noun: unsurprisingly, ‘foot’. With the use of another zhi 之, which was the same foot over a ‘starting line’ (yi 一) in the function of ‘to go’, however, the zhi 止 ‘foot’ with no line underneath came to function as the antonym: ‘to stand’ or ‘to stop’. The function of ‘foot’ was later assigned to another syssemantograph, zhi 趾 (similarly to how yun 雲 ‘cloud’ was separated from yun 云 ‘to speak’), which in modern vernacular Chinese functions in the compound jiaozhi 脚趾 ‘toe’. The original pictogram zhi 止 continued to be used as ‘to stop’.

But let us, following Sobchak’s advice to the Dude from The Big Lebowski, ‘forget about the toe’ for a bit, and move on to ting 停. Xu Shen classifies ting 停 as a phono-semantic glyph, meaning that one side (ren 人 ‘human being’) represents the semantic function and the other (ting 亭 ‘pavilion, watchtower, kiosk’) represents the phonetic value. More modern etymologies, however, seem to treat ting 停 as a syssemantogram, because the right-hand character element pulls a certain amount of semantic weight. It shows something that is built high (gao 高) and is held in place by nails (ding 丁); thus it also had the function of something that is ‘settled’ or ‘fixed’ in place. Thus ting 停, a bit more emphatic than zhi 止, is what you tell someone to do when they are to ‘make like a watchtower’ and ‘nail themselves to the spot’.

So, apart from tingzhi 停止, ting 停 is used in modern Chinese compound words like tingche 停车 ‘to park (a vehicle)’; tingchechang 停车场 ‘parking lot’; buting 不停 ‘incessant’; tingxia (lai) 停下(来) ‘to stop (for a while)’; zanting 暂停 ‘to suspend, to pause’; tingliu 停留 ‘to stop over’; tingdian 停电 ‘to cut power’; tingchan 停产 ‘production halt’; tinghuo 停火 ‘ceasefire’; tingkao 停靠 ‘to come into port, to stop at, berth’; tingdun 停顿 ‘halt’; and tingzhan 停战 ‘armistice’. And zhi 止, apart from the aforementioned tingzhi and jinzhi 禁止, is used in compounds like zuzhi 阻止 and fangzhi 防止 ‘to prevent’; dao… weizhi 到…为止 ‘so far, up to this point, until’; buzhi 不止 ‘incessant’ (same as buting above); jiezhi 截止 ‘to close’; zhizhi 制止 ‘to curb’; juzhi 举止 ‘bearing, manner, mien’; zhongzhi 中止 ‘to cease’; zhixue 止血 ‘to staunch (bleeding)’; zhiteng(yao) 止疼(药) ‘painkiller’; feizhi 废止 ‘to repeal, to annul, to abolish’.

As I mentioned above, ting 停 is not commonly found in Classical-era texts. Prior to the Qin-Han transition, it is found only in texts (that we know of) belonging to the Matrical School (Zhuangzi 《莊子》 and Liezi 《列子》) and the Military School (Wuzi 《吳子》). Yet interestingly, the Zhuangzi places the word ting 停 in the mouth of Confucius! Observe.

「何謂德不形?」曰:「平者,水停之盛也。其可以為法也,內保之而外不蕩也。德者,成和之修也。德不形者,物不能離也。」

‘And what do you mean by the realisation of these powers not being manifested in the person?’ pursued [Duke Ai of Lu]. [Confucius] replied, ‘There is nothing so level as the surface of a pool of still water. It may serve as an example of what I mean. All within its circuit is preserved (in peace), and there comes to it no agitation from without. The virtuous efficacy is the perfect cultivation of the harmony (of the nature). Though the realisation of this be not manifested in the person, things cannot separate themselves (from its influence).’

Zhuangzi 《莊子》, ‘The Seal of Virtue Complete’ 德充符 5.4

The presence of Confucius as a (mostly-sympathetic, occasionally-comic) literary character in the Zhuangzi and the Liezi, two texts from a competing school to his own, is worthy of note in itself. And the fact that in one of these texts, he is using language used nowhere else in the Classical canon, but instead seemingly borrowed from the Military School, is equally worthy of note. I have a hypothesis about why this is, but given that our concerns here are lexicographical, this may not be the best place to explore that hypothesis.

Here Confucius is using ting 停 as an adjective, modifying ‘water’ in the function of ‘still’ or ‘unmoving’. This is in contradistinction to the contemporary Military School text Wuzi, where the same lexeme functions expressly as a verb, ‘to stop’ or indeed ‘to halt’ as if fixed in place. Is Confucius being emphatic here? Is he making an inter-textual reference linking the Zhuangzi to the Wuzi? It’s difficult to tell, but my inclination is toward the former interpretation rather than the latter. He is talking of a pool of water that is absolutely still, as if fixed down.

One is reminded here of the double function of the Semitic triliteral w-q-f seen in Qur’ānic Arabic as waqafa وقف ‘to be made to stand, to stop, to be steadfast’ and in Classical Syriac as wqaf ܘܩܦ ‘to cleave to, to follow, to adhere’, which appears in the Peshitta edition of Acts 8:29, where the Holy Spirit is telling the apostle Philip to ‘stick to’ (Syr. wqaf ܘܩܦ, Gk. κολλήθητι) the chariot, like glue (Gk. κόλλα ‘glue, gum, paste’). Following this Greek root back into the LXX, we can see that it corresponds often to the Hebrew dābaq דבק ‘to stick to, to pursue, to join’ (e.g. Deu 10:20; Rth 2:8; 2 Ki 3:3). Clearly w-q-f is not a direct cognate to d-b-q, but the instance of the same root functioning in Arabic as ‘to stop’ and in Syriac as ‘to stick to’ (like glue), is parallel to the double functionality of the Chinese ting 停.

The way this verb actually functions in Semitic, is that it likens the subject to paste—this is why the Greek root κολλάω is used (cognate to the Russian клей or indeed, the English ‘clay’!). Thus, the imagery is very much of the person, the human being, as being formed from dust, as being moulded as if from clay that can be stuck to something. In several cases where dābaq דבק appears in the Psalms, for example, the explicit image is of the human being as sticky clay:

יבשׁ כּחרשׂ כּחי וּלשׁוני מדבּק מלקוחי ולעפר־מות תּשׁפּתני׃

My strength is dried up like a potsherd; and my tongue is glued to my throat; and thou hast brought me down to the dust of death. (Ps 21:15)

כּי שׁחה לעפר נפשׁנוּ דּבקה לארץ בּטננוּ׃

For our soul has been brought down to the dust; our belly has cleaved to the earth. (Ps 43:25)

But, most tellingly:

דּבקה לעפר נפשׁי חיּני כּדברך׃

דּרכי ספּרתּי ותּענני למּדני חקּיך׃

דּרך־פּקּוּדיך הבינני ואשׂיחה בּנפלאותיך׃

דּלפה נפשׁי מתּוּגה קיּמני כּדברך׃

דּרך־שׁקר הסר ממּנּי ותורתך חנּני׃

דּרך־אמוּנה בחרתּי משׁפּטיך שׁוּיתי׃

דּבקתּי בעדותיך יהוה אל־תּבישׁני׃My soul has cleaved to the ground; quicken thou me according to thy word. I declared my ways, and thou didst hear me; teach me thine ordinances. Instruct me in the way of thine ordinances; and I will meditate on thy wondrous works. My soul has slumbered for sorrow; strengthen thou me with thy words. Remove from me the way of iniquity; and be merciful to me by thy law. I have chosen the way of truth; and have not forgotten thy judgements. I have cleaved to thy testimonies, O Lord; put me not to shame. (Ps 118:25-31)

This is from Psalm 118, which is an acrostic Psalm for which this root dābaq serves as the model for the letter dāl(et) ד. Here is the commentary of St Theophan the Recluse on these verses—who, by the way, was at one point a monk in Palestine and was versant in both Hebrew and Arabic, and whose comments on the Semitic triliterals come from his education in those two languages!

‘To cleave to the earth or anything earthly is death to the spirit, but it already cries, it is already in motion, it is already quickened, but quickened only enough to realise the deadness of sin and passions that shackles him. It has not yet the strength to break open these bonds; it wants to break out of them, but feels that they are so strong that it will not be able to cope with them. For that reason, he prays to God with life-giving strength…’

And subsequently:

‘This tearing away of the heart from sin never happens alone; with it always goes adherence to the opposing good. They go hand in hand, and insofar as one is strong, so much is the other strengthened. The heart cannot be without attachment, for that is its nature. Giving up one, it becomes attached to the other…’

The human being has a choice—the choice which was recognised by the character of Confucius in the Zhuangzi. The human being (wu 物) cannot be separated (bu neng li ye 不能里也) from his influences! Just as the still water of a pond by its very fixity also fixes what is around it, so too the human being gravitates toward, submits to, and adheres to what he loves: either instruction or rebellion; either neighbour or self; either the wilderness with its rivers and trees and sky, or the city with its buildings and walls; either God or the princes of this world; either life or death.

~~~

For zhi 止, one can see parallels to the familiar Semitic triliteral š-b-t ש-ב-ת, which appears in the Tōrah as šābat שבת ‘to cease, to desist, to rest, to put an end to’, in the Syriac Peshitta as šabét ܫܒܬ ‘rest, Sabbath’ (Heb 4:4,9), and in the noble Qur’ān as subātan سباتاً ‘rest, Sabbath’ (25:47:8). This term is derived from Akkadian, šabattu, in reference to a ‘day of cessation’—and is obliquely related in its consonantal structure to šebutu, the ‘seventh’ day of the month.

I want to point again to the graphical distinction between the two zhis. This zhi 止 in its archaic form is distinguished only from the other zhi 之 by a single line (yi 一), a ‘starting line’. The first functions as ‘to stop’, the other as ‘to go’. But if you’re running in a race, or even if you’re not running in a race but just getting from point A to point B, you’re going to need to rest, either for a pit stop or once you reach your destination. This is how the term is used Classically.

翩翩者鵻、載飛載止、集于苞杞。

王事靡盬、不遑將母。The filial doves keep flying about,

Now flying, now stopping,

Collecting on the bushy medlars;

But the king’s business was not to be slackly performed;

And I had not leisure to nourish my mother.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Deer Call 鹿鳴之什, ‘Four Steeds’ 四牡 4

In this Ode—this is a common theme that crops up in the Odes—the birds are actually the models of the virtues. They don’t toil and labour, and they certainly don’t serve kings. One may be tempted to think of the Gospel of Saint Matthew (Matt 6:26-27) when reading such verses, and perhaps with good reason, but let’s not shortcut the central consideration here. The propaganda of the Zhou state, as well as Chinese states which succeeded it, exalts the human beings of the Illustrious Pattern (huaren 华人) of Zhou, above the ‘barbaric’ human beings outside Zhou-ruled states in the four cardinal directions (siyi 四夷), who are likened to ‘birds and beasts’ (qinshou 禽兽) without proper rituals or morals or proper regulation of feelings. The rhetoric of the Chinese Classics deliberately subverts this propaganda. It’s the birds and beasts who actually know how to behave. It’s the birds and beasts which follow the Pattern of Tian 天. We human beings are the screw-ups: we human beings are the ones who end up prioritising (or being forced to prioritise) ‘the king’s business’ over the business of caring for those closest to us.

Notice that the Ode provides baoqi 苞杞 ‘bushy medlars’ (actually likely a kind of willow or wolfberry plant) for the doves to rest (zhi 止) in; in the prior verse the Ode mentions them gathering in baoxu 苞栩 ‘bushy oaks’. Legge’s translation ‘bushy’ isn’t wrong, per se, but it lacks a certain colour. A better one would be ‘blooming’, ‘luxuriant’, ‘lush’, ‘growing in abundance’—the term bao 苞 implies an encompassing (bao 包) even exploding (pao 炮) overgrowth of foliage. The doves are provided with everything they could ever want—and the pitiable human is scurrying around driving his four steeds to exhaustion, trying to please some jerkass king who won’t let him go home to take care of his poor parents.

Here we can make a meaningful comparison between the Odes and the Tanakh—not that one is a reference for the other, but they are saying certain things in parallel. We do a certain disservice to the original text by dividing it up into chapters and verses—it’s a convenient reference tool to index and cite Scripture from, don’t get me wrong, but we always have to keep in mind that the original text did not have them. So the last thing God does in Genesis 1 is to give to the living souls of His creation—every beast (ḥayyat חית) of the earth and to every bird (‘ôf עוף) of the air—the sustenance of every plant bearing seed and every green thing for food. And the first thing God does in Genesis 2, after this is complete, is to take His rest (wayyišǝbbōt וישבת).

This rest is also an Edenic gift to the animals, which is made clear in the Law, in Exodus:

שׁשׁת ימים תּעשׂה מעשׂיך וּביּום השּׁביעי תּשׁבּת למען ינוּח שׁורך וחמרך וינּפשׁ בּן־אמתך והגּר׃

Six days you shall do your work, but on the seventh day you shall rest; that your ox and your ass may have rest, and the son of your bondmaid, and the alien, may be refreshed. (Ex 23:12)

Notice that the criticism of the king in ‘Four Steeds’ serves the exact same purpose, lexically, as the gift of rest after the gift of vegetation in Eden to the animals and the subsequent command to the Hebrews in the Law in Exodus. The doves get their šābat שבת, their rest (zhi 止) from God, or Tian. But the human voice of the Ode trying to fulfil the will of an earthly king must drive his four horses ‘without stopping’, until ‘they panted and snorted’, and he himself is worried about his parents.

One piece of sacred literature from West Asia (the Tanakh); and the other piece of sacred literature from East Asia (the Odes)—speaking in parallel, in different languages. Delivering a parallel teaching. It is a thing of beauty. It doesn’t matter which river system your civilisation is built on, my brother: man cannot precede the doves. It is written. Glory to ’Elōhîm for all things.