The lexicology of hou 後 and 后

Behold, I establish my covenant with you and your descendants after you. (Gen 9:9)

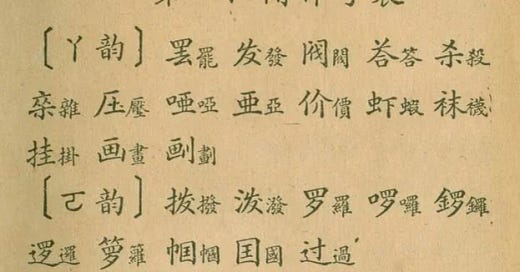

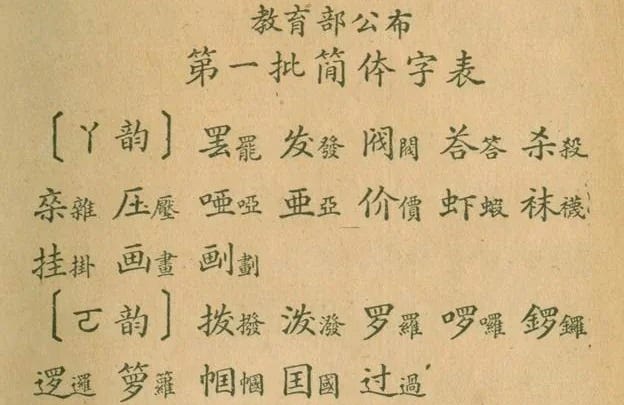

The history of character simplification in Chinese is actually a far longer, far messier one than many modern Chinese people would admit. Very rarely does the story actually adhere to the Gangtai propaganda line one may occasionally see, about how ‘evil commies came and erased history and brainwashed people into using ugly lazy heartless simplified characters in 1956’… or, conversely, the mainland propaganda ‘good socialists came and enlightened the people by magically making the script easier to learn’.

In fact, the simplified characters are actually, in significant proportion, adopted organically from far older archaic character forms. Many of them signify a restoration of classical-era pre-Qin usages. This is the case, for example, with yun 云, which originally functioned both as the noun ‘cloud’ and the verb ‘to say (authoritatively)’. In post-Qin (220 – 206 BC) usage, a different graphical form of yun 雲 was created specifically for the function ‘cloud’. In 1956, what the PRC State Council actually did was to restore the archaic usage of yun 云 to mean both ‘cloud’ and ‘to say’ (though by that time, the latter function had largely fallen out of vernacular usage in favour of shuo 说 and jiang 讲).

Today, too, we’re dealing with a very convoluted lexicographical tale of convergent evolution, complex usage and character simplification. So buckle up! We are dealing with two closely-intertwined characters: hou 後 and its homophonous (near-)synonym hou 后, which today pulls double duty as the simplified version of the former character.

Hou is a pretty common one, despite the complexity of its history. It’s the 48th most common character in written Chinese. Its primary function on its own as is a preposition: ‘in back of’, ‘behind’ or ‘after’. Wo dei paidao duiwu houmian 我得排到队伍后面, ‘I have to go to the back of the queue’; liang dian yihou wo meiyou renhe shiqing 两点以后我没有任何事情, ‘I don’t have anything to do after 2:00’. As one can see even here, it’s used in common compounds like houmian 后面 ‘rear, the back side of’ and yihou 以后 ‘afterwards, subsequently’. It’s also used in ranhou 然后 ‘thereafter, then’; zuihou 最后 ‘final’; zhihou 之后 ‘after’; houlai 后来 ‘later’; jinhou 今后 ‘hereafter’; suihou 随后 ‘soon following’; beihou 背后 ‘behind (the back of)’; houhui 后悔 ‘to regret, to repent’; xianhou 先后 ‘priority’; houguo 后果 ‘consequence’; shenhou 身后 ‘posthumous’; cihou 此后 ‘after this’; houyi 后裔 ‘offspring, progeny’ and huanghou 皇后 ‘empress-consort’.

Wait… ‘empress-consort’? What—?

The two characters hou 後 and 后 are equally ancient, but have markedly different origins. The first one, hou後, ideographically represents a foot (zhi 之、止、夂) bound by a piece of rope or silk thread (yao 幺) which prevents it from walking or moving forward along a path (chi 彳 = xing 行). The clear original function of this ideogram is to indicate something that is physically behind another. The second one, hou 后, is an equally-archaic character that (similarly to dao 道) represents a mother (mu 母) giving birth to a newborn child (yu育). Originally this lexeme represented an ‘heir’, a ‘successor’—but it quickly gave rise to the connotations of a dynastic ‘sovereign’ or indeed, the sovereign’s mother, the ‘empress-consort’. The Erya 《尔雅》 clarifies that these are two separate characters with two separate families of connotation, though they are connected. It links hou 后 to various synonyms of ‘king’, ‘lord’ or ‘monarch’ (wang 王; di 帝; huang 皇; bi 辟; hou 侯; jun 君), and hou後 to a character for ‘descendants’, kun 昆.

But this bifurcation in function, despite the subtlety with which it appears in classical lexicography, is nonetheless demonstrated in the Classics themselves. Take, for example, the Odes:

江有汜、之子歸、不我以。

不我以、其後也悔。江有渚、之子歸、不我與。

不我與、其後也處。The Jiang has its branches, led from it and returning to it.

Our lady, when she was married,

Would not employ us.

She would not employ us;

But afterwards she repented.The Jiang has its islets.

Our lady, when she was married,

Would not let us be with her.

She would not let us be with her;

But afterwards she repressed [such feelings].Book of Odes 《詩經》, Shao and the South 召南, ‘River Branches’ 江有汜 1-2

In ‘River Branches’, the first hou 後 is clearly used as a preposition: ‘afterwards’. The other hou 后 is most often used in the Odes as a noun or

a title, meaning ‘sovereign’ or ‘successor’. See:

下武維周、世有哲王。

三后在天、王配于京。Successors tread in the steps [of their predecessors] in our Zhou.

For generations there had been wise kings;

The three sovereigns were in heaven;

And king [Wu] was their worthy successor in his capital.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Wen Wang 文王之什, ‘Xia Wu’ 下武 1

There can be found similar bifurcations in Semitic languages. I’ve already discussed some of the functionalities of ḵ-l-f خ ل ف ‘to change’, ‘to differ’, ‘successor’ in Arabic in conjunction with the Sinitic character yi 异. But there is another triliteral root in Semitic languages that can fulfil one of the same functions: the Qur’ānic root ’-ḵ-r أ خ ر which carries the functions of ‘to delay’, ‘to postpone’, ‘to give respite’, ‘hereafter’ or ‘in subsequent generations’—and which finds its cognate in the Biblical Hebrew triliteral ’-ḥ-r א-ח-ר, with a similar lexical range. Just as with hou 後 and hou 后, each of these Semitic roots carries a functional appeal to posterity. Just as ḵ-l-f خ ل ف (similarly to the Sinitic yi 裔) implies a change (yi 异) of generations like the shedding of leaves from season to season, and thus also connotes succession; so too ’-ḵ-r أ خ ر evolves to fulfil a similar lexical function in the Semitic languages. For example:

לבנים נפלוּ וגזית נבנה שׁקמים גּדּעוּ וארזים נחליף׃

The bricks are fallen down, but we will build with hewn stones: the sycamores are cut down, but we will change them into cedars. (Isa 9:10)

But, here is the other root in the same function:

עליה לבניכם ספּרוּ וּבניכם לבניהם וּבניהם לדור אחר׃

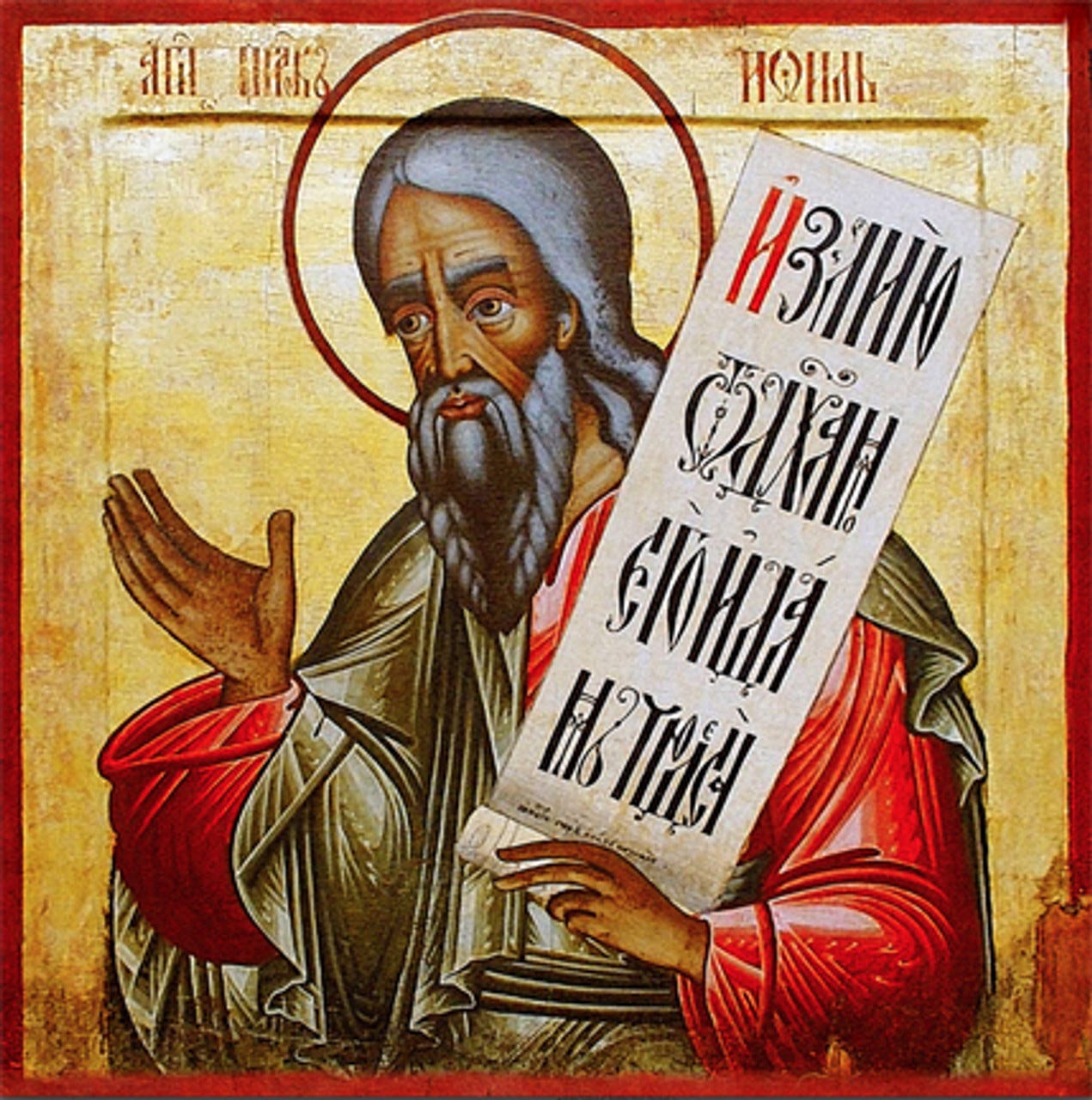

Tell your children of it, and let your children tell their children, and their children another generation. (Joel 1:3)

Usages fall in and out of favour organically. In modern Arabic, the use of the root أ خ ر to mean ‘behind’ or ‘after’ is comparatively rare. Despite its being attested frequently as al-Ākhirati الاخرة ‘the Hereafter’ in the Qur’ān, one doesn’t really hear it used as a preposition ‘behind’ in modern Arabic: instead one hears khalf خلف and perhaps warā’a وراء. (On the other hand, the same root’s use in modern Arabic as an adjective, ’ukhrā أخرى ‘other’, is very common indeed!) Linguistically, then, perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that the lexeme hou 后 displaced hou 後 and assumed its functions for the Mainland Chinese houyi 后裔!

Still…

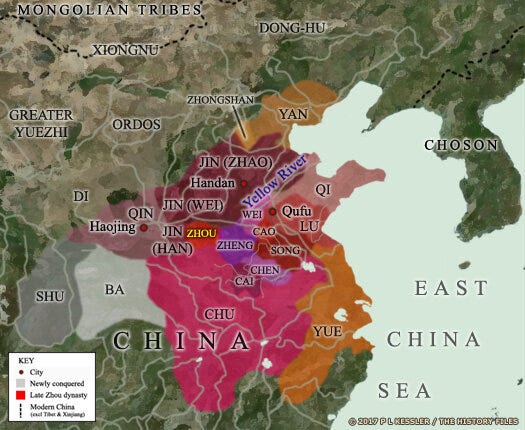

The Ode ‘First Month’ 正月 in the Decade of the Minister of War 祈父之什 is worth reading in its entirety, because it encapsulates the strident critique the authors of the Classics brought to bear against the decline and decadence of the late Zhou. It bears the mark of an author consumed with prophetic rage against his own generation, and against the manifest oppressions, injustices, inequalities and falsities of his own age (哀今之人、胡為虺蜴。 ‘Alas for the men of this time! Why are they such vipers and asps?’), which is probably set, from a literary standpoint, toward the beginning of the eighth century BC (given the reference to Baosi). But its being included in a work of literature read by people in the Warring States at the very tail end of the Zhou, indicates that the critique is in fact being aimed against this generation—the one for whom it is presented! The author mourns:

父母生我、胡俾我瘉。

不自我先、不自我後。Ye parents who gave me birth!

Was it to make me suffer this pain?

[Why was this time] not before me?

Or [why was it] not after me?Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Minister of War 祈父之什, ‘First Month’ 正月 2

A Classical Chinese reader is meant to be shocked by these lines, which is very much so on parallel in sentiment with Jeremiah 20:14-18 (‘Cursed be the day on which I was born!’). This extreme attitude of spite for his parents, for causing him to exist in such a generation and in such an age, is one which runs completely against the expectations of filial piety that the Classics otherwise seek to inculcate. Yet the narrative voice of ‘First Month’, like Jeremiah, cannot help but prophesy to those zi wo hou 自我後, to those who come after him. 燎之方揚、寧或滅之。赫赫宗周、褒姒滅之。 ‘The flames, when they are blazing, / may still perhaps be extinguished; / but the majestic honoured capital of Zhou, / is being destroyed by Si of Bao.’

This is the warning that the compilers of the Classics left to those who come after. As if to say: ‘you are not in any better position than your predecessors!’ Those in the Warring States are being both cautioned and to some degree comforted, that, however much they are at risk of calumny, predation, oppression and destruction at the hands of the rich and violent—this has happened before and will happen again.