The lexicography of yun 云

‘And a voice came out of the cloud, saying, “This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!”’ (Luke 9:35)

In this lexicography series, I have profiled several Chinese lexemes which carry the gloss ‘to say’ or ‘to speak’. These include: yan 言, yue 曰, shuo 說 and dao 道. To this I am adding yet another: yun 云! One thing that can be said for Chinese people both ancient and modern: they love to talk. And their lexicon very much points to this! There is, to my mind, nothing either factually more wrong, nor normatively more ignorant, than the shoddy and insulting Orientalist stereotype of the ‘inscrutable’, ‘silent’ Chinese.

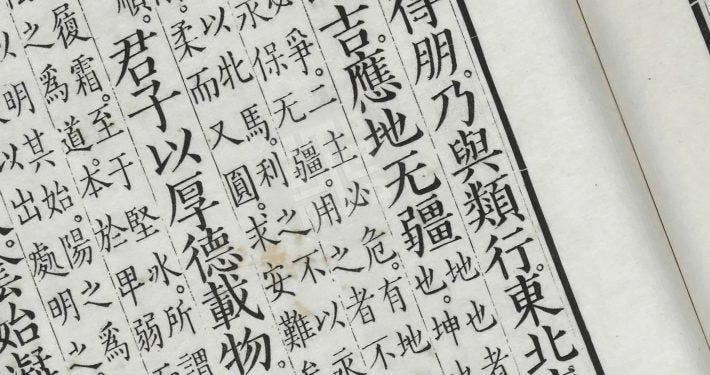

The character yun 云 originally indicated the shape of a cloud. The Shang Dynasty oracle-bone script ideogram shows a cirroform wisp curling off of a layer of sky: clearly an inspiration for the symbol that Avatar: the Last Airbender uses for its fictional-universe Air Nomads. In Classical Chinese, the same character yun 云 was used for both the nominal function of ‘cloud’, and the verbal function of ‘to say’ or ‘to speak’. This may be on account of other speech-related words like yan 言 or yue 曰 being near-homophones; or alternatively it may be a semantic drift: metaphorically likening the hubbub of public conversation to a low-hanging cloud or a fog. In order to distinguish these two characters from each other, Classical authors began to differentiate the noun ‘cloud’ using the derived character yun 雲, which explicitly shows a raincloud, from yun 云 which continued to be used in the verbal function of ‘to say’. In modern times, the Communist-era process of character simplification actually restored the archaic Shang Dynasty usage, so that the same character yun 云 once again refers to ‘cloud’.

It should be noted that in classical Chinese, yun 云 has numerous other glosses that serve in various functions such as ‘to have’, ‘to move’, ‘to socialise’, ‘if’, ‘many’ (particularly if the character is doubled as yunyun 云云) or as a particle or filler word. But in classical Chinese, the primary difference between yun 云 and the other lexemes linked to the function of speech, is that yun 云 is generally used when quoting or citing an authority in the third person. Let’s look at some examples below.

故聖人云:我無為,而民自化。

Therefore a sage has said, ‘I will do nothing (of purpose), and the people will be transformed of themselves.’

Daodejing 57

子張問曰:「《書》云:『高宗三年不言,言乃歡。』有諸?」

Zi-zhang asked, saying, ‘The Book of History says, that “Gao Zong for three years did not speak; and that when he did his words were received with joy.” Was it so?’

The Record of Rites 《禮記》 4.167

子貢曰:「《詩》云:『如切如磋,如琢如磨。』其斯之謂與?」

Zi-gong replied, ‘It is said in the Book of Poetry, “As you cut and then file, as you carve and then polish.” – The meaning is the same, I apprehend, as that which you have just expressed.’

Analects 1.15

One should be able to get the picture from the examples above. The term yun 云 corresponds to hearsay: to a pronouncement from a third-person source not immediately present, that both the speaker and the hearer are meant to accept as authoritative. In each of these examples, the one who has said (yun 云) is either a sage, or another ancient Classic like the Odes or the Documents. One is reminded of the Lord’s pronouncement in Exodus, just when the Hebrews had entered Sinai:

ויּאמר יהוה אל־משׁה הנּה אנכי בּא אליך בּעב הענן בּעבוּר ישׁמע העם בּדבּרי עמּך וגם־בּך יאמינוּ לעולם ויּגּד משׁה את־דּברי העם אל־יהוה׃

And the LORD said to Moses, ‘Lo, I am coming to you in a thick cloud, that the people may hear when I speak with you, and may also believe you for ever.’ Then Moses told the words of the people to the LORD.

Exodus 19:9

The Semitic wordplay between ‘ānān ענן ‘(mass of) cloud’ and ’āman אמן ‘to support, to confirm, to be faithful, to uphold, to nourish’ in Exodus is subtle (it’s an internal rhyme, not a shared root—’alef א and ‘ayin ע are, after all, two discrete and different consonantal sounds), but it serves the same function as the dual connotation of yun 云 in classical Chinese. Even before He delivers the Law, God is setting Himself up as authoritative and credible, even above and beyond reference to trusted elders (with their ‘clouds’ of white beard) and the general hubbub of the crowds and ‘clouds of witnesses’. The ‘sign from the cloud’ in Genesis 9, or the ‘voice from the cloud’ in Exodus 33 (or Luke 9!) all serve this purpose: to establish the Lord as an authority in His pronouncements and commands, over the people and beyond the people’s reproach.

It is equally interesting to examine, through the use of this function of the lexeme yun 云, which sources the ancient Chinese considered credible or trustworthy. From these Classical-era Zhou texts, we can see and understand that both the Ritual School (Rujia 儒家) and the School of Mo (Mojia 墨家) considered the Book of Documents or Shangshu 《尚書》 to be authoritative, and used the word yun 云 to appeal to this work. Likewise, even Matrical School authors like the notably irreverent and satirical Zhuang Zhou 莊周 used the word yun 云 in reference to the person of Confucius, as in the Miscellaneous Chapters of the Zhuangzi 《莊子》 (though here, he is using Confucius’s authoritative voice to undermine Confucius’s authority before the ‘fixed law’). We have evidence also that later Matrical scholars and writings like the Huainanzi 《淮南子》 treated the Book of Odes or Shijing 《詩經》 as authoritative.

This is why I hold, from a lexicographical standpoint, that it is at least somewhat misleading to speak of a ‘Hundred Schools of Thought’ or Zhuzi baijia 諸子百家 during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods of Classical China. Were there a large number of teachers who established a large number of schools during this time? Yes. Confucius had his school and his followers. So did Mo Di, so did Li Kui, and so did Zhuang Zhou. In that sense, yes, we can say that there were a ‘Hundred Schools’. But the character and influence of these schools overlapped significantly with each other, and to a significant extent they shared a common pool of shared references.

We can see even from the fragmentary picture we are afforded through pre-Qin texts, that the ‘Hundred Schools’ (with the noteworthy exception of Li Kui’s Legal School, which referred to its own text and disregarded the others) had a shared corpus of ancient and authoritative Scriptures which they all studied and to which they all deferred. The only Classic, after all, which we know with reasonable assurance that Confucius actually put his hand to was the Spring and Autumn Annals, and this is generally considered to have been written last among the Five Classics, or else concurrently with the Book of Rites.

The idea of a fast-and-firm opposition between the Schools is of much later provenance. This is what I call the Breakfast Club model of the Hundred Schools: Confucius the ‘nerd’; Sun Wu the ‘jock’; Zhuang Zhou the ‘loner’ or ‘burnout’; Li Kui the ‘prep’. But if this analogy holds, then that means we moderns (including post-classical Chinese!) are all Paul Gleason, and we all fundamentally misunderstand classical Chinese writings by interpreting them through a ‘philosophical’ lens.

And, this much is true: the neo-Confucianism of the Chinese Song to Ming Dynasties (960 – 1644 AD) was conformist. It was misogynist. It was punitive. It was pro-establishment, pro-empire. It was an apologetic ideology of the state, and a ruling-class ideology of the bureaucratic intelligentsia. It did have a hidebound, intransigent and reactionary character—even by the standards of its own time. All of the charges that May Fourth Movement authors like Lu Xun and later communists like Mao Zedong laid at the foot of this permutation of Confucian ideology, did have a solid basis in fact. But this characterisation does not and cannot explain the willingness of Ritual scholars like Fan Ying 樊英 (fl. 120s AD) to dare the wrath of the Han Emperor by criticising him and flouting his authority to his face in the name of Tian 天, very much like a Hebrew prophet!

In a similar vein, there were discrete historical periods, such as the Three Kingdoms period (220 – 280 AD) with the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, where the individualist, anarcho-primitivist, Alan Watts New Age pop hermeneutic of Matrical School texts did come close to referring to the actual character of Daoism. Many took refuge in the verses of the Daodejing and sought a way through it ‘back to the roots’, particularly in eras of social stagnation or decline. The implicit romanticism, spontaneity and closeness to nature inherent in the core Matrical commentaries did have a definite appeal to recluses, poets and dissatisfied officials. This appeal did occasionally congeal into a definite countercultural posture… though to say this was the case either in classical times or throughout Chinese history is to engage in some very selective historicism. Laozi and Zhuang Zhou definitely had ideas about how governments should work, that (to say the least) do not always line up with modern Western liberal, let alone libertarian, anarcho-primitivist or individualist, ideals.

Thus, like the high school ‘clique’ stereotypes which The Breakfast Club sets out to demolish, the distance between later manifestations of Confucianism and Daoism masks the corpus of shared reference that is yun 云 between Matrical and Ritual School commentaries. Burton Watson is, in fact, correct that we should see Confucius and Zhuang Zhou as complementary, not opposed, teachers.

Both the Ritual and Matrical Schools appealed to the Odes and to the Changes. And Confucius and Zhuang Zhou both, for example, acknowledged the human need for an authority of some kind—and both were loath to place that authority in any merely human institution. For Confucius (who very notably claims not to have ‘created’ or ‘invented’ zuo 作 anything, but merely ‘transmitted’ shu 述 what he has learned; see Analects 7.1), authority is vested in the wisdom of ancient rituals and music, which have their root not in human will or creativity but in Tian (which is why the Rites follows after the Odes in the Confucian corpus; see Analects 3.8). Zhuang Zhou appeals to the authority of nature much more directly than Confucius does; as a result, he tends to dismiss the mediating value of the ancient rituals and focus on the direct study of Tian through the Changes.

~~~

One further note on shuo 說 and yun 云. In the difference in functionality between these two lexemes for ‘speech’, lies the key to understanding that Bishop Aluoben may have been writing in Chinese, but that he had a Semitic mind and an Antiochian understanding of Scripture.

The Xuting Mishisuo Jing 序聽迷詩所經 begins with the sentence:

爾時彌師訶說天尊序娑法云。

At that time, the Messiah spoke [what] the Heaven-venerated YHWH had said.

But let’s keep in mind, when we read such a passage, the Classical glosses of each verb, both of which are more limited in range than the general yan 言 or yue 曰. The term shuo 說 bears the glosses ‘to explain’ or ‘to pledge’ or ‘to promise’; while the term yun 云 is used to cite a third-person authority. YHWH (Xusuofa 序娑法) is being cited as the Voice from the cloud, the Speaker of the Mosaic Law of Exodus 19:9. For Aluoben, Jesus is the locum tenens, the paizi-bearer, whose speech is naturally subservient or submissive to that prior voice. Jesus may be speaking, but everything He speaks is in fact the Voice of His Father.