The lexicology of xian 顯

And the Lord appeared again at Shiloh, for the Lord revealed himself to Samuel at Shiloh by the word of the Lord. (1 Sam 3:21)

Before I begin this entry—and actually, it happens to be a very apt and apposite spot to do so—I feel I should make a small but necessary note of self-criticism. I have been using the term ‘ideogram’ and ‘ideographic’ in my description of Chinese characters. This usage of mine is misleading, and it may obscure more than it clarifies. In my own (partial) defence, my use of the term was meant in contradistinction to ‘phono-semantic’ characters in Chinese. Yet ‘ideogram’ is very much a category of the Western lens, which Chinese people would not use to think about their own language.

Traditionally—that is to say, before the imposition of Western categories—Chinese characters were already being classified dynamically. Even if the categories themselves needed some fine-tuning from subsequent scholarship, this was still the broad schema into which they were placed from a native Chinese perspective. Xu Shen, the author of the Shuowen jiezi 《说文解字》 to which this Chinese lexicography series is so deeply indebted, identified six forms (liu shu 六书 ‘six books’) into which Chinese characters could be classified. These are: pictograms (xiangxing 象形); icons (zhishi 指事); syssemantographs (huiyi 会意); loangraphs (jiajie 假借); phonosemantic glyphs (xingsheng 形声); and derivative cognates (zhuanzhu 转注). Of these six categories, phonosemantic glyphs are by far and away the most common, making up about 80% of the characters found in modern Chinese dictionaries and glossaries. The things we tend to think of as obvious about other languages, actually are very much not so. Chinese, far from being an ideographic language, actually has a dynamic mixed writing system that blends pictorial-semantic and phonetic elements.

Speaking of which, the character discussed here is xian 顯 (simplified 显), commonly glossed as ‘clear’, ‘manifest’, or ‘to reveal’. This character is a syssemantograph, meaning it is a composite of two or more semantic elements meant to convey a separate function or lexical range. The pictographic elements are a sun (ri 日) shining down on a braid of silk (si 絲), and a human head with a prominent eye (ye 頁). The two pictographic elements, taken together, are meant to show a bright (Erya connects xian 顯 to xi 熙 ‘splendid, glorious, bright’ and lie 烈 ‘bright, blazing’) and conspicuous item directly in front of (another xian 先) a person’s line of sight.

Xian 显 is a very common character in Chinese, being used in everyday compounds like mingxian 明显 ‘clear’; xianshi 显示 ‘to display, to show, manifest’; xianran 显然 ‘obvious, evident’; xiande 显得 ‘to seem’; xianzhu 显著 ‘outstanding, notable, remarkable’; xianxian 显现 ‘appearance’; xianlu 显露 ‘to reveal’; xianchu 显出 ‘to express’; xianhe 显赫 ‘illustrious’; and zhangxian 彰显 ‘to make manifest’. It’s also often used in technical language to describe manmade devices that display or magnify something: xianshiping 显示屏 ‘display screen’; xianshiqi 显示器 ‘computer monitor’; and xianweijing 显微镜 ‘microscope’.

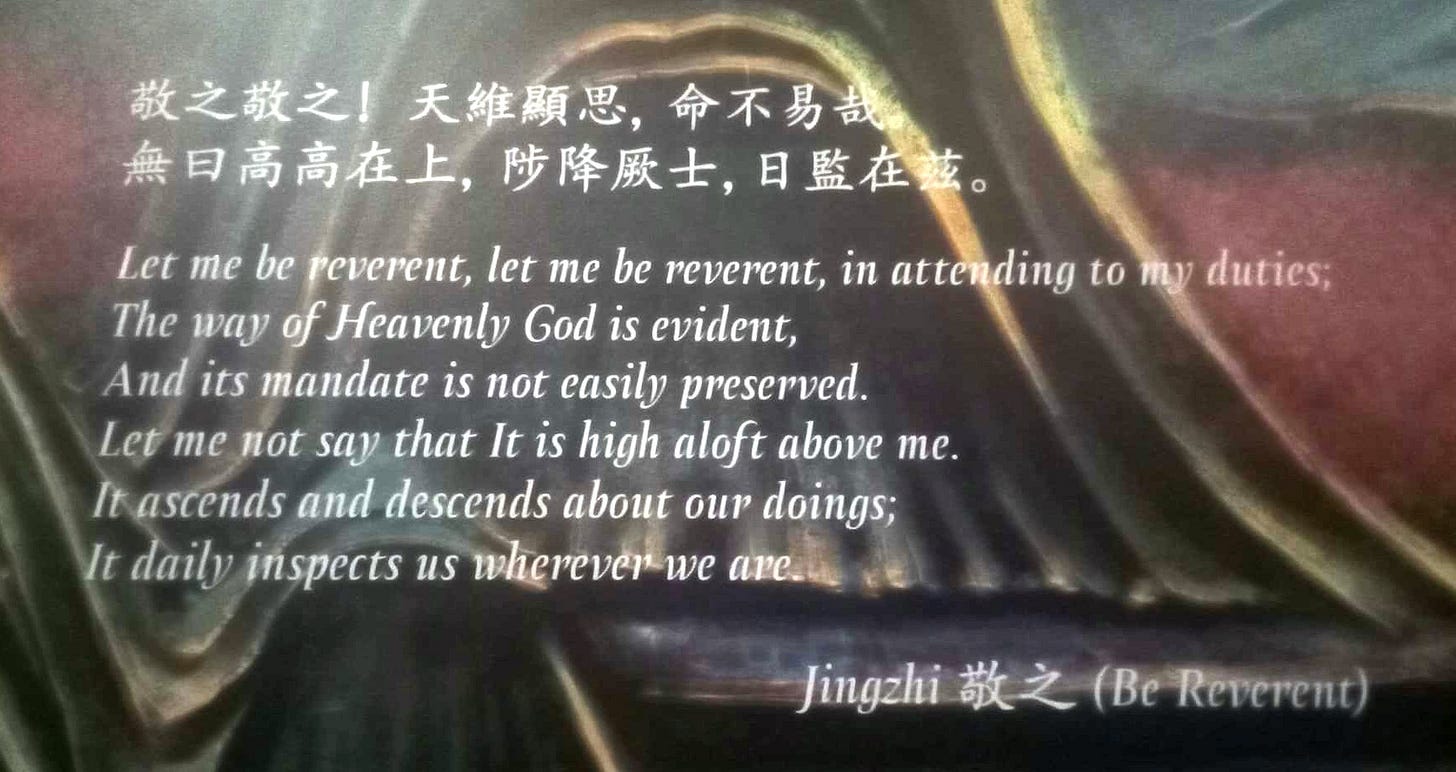

Two years ago, in the spring, the Minneapolis Institute of Art hosted ‘Eternal Offerings’: an exquisite collection and display of Chinese bronzes from the Classical period (Shang, Zhou, Spring & Autumn and Warring States), designed by Tim Yip and curated by Liu Yang. At the front of the exhibit, there was a lengthy quote from the Book of Odes.

The authors of the Odes were onto something important here—particularly at the end.

The Semitic triliteral n-g-d נ-ג-ד (Hebrew nāgad נגד, Syriac ngad ܢܓܕ, Ge’ez nägädä ነገደ ‘to travel’) follows a very similar lexical trajectory to xian 顯. The root itself indicates something ‘in front’, ‘in sight’, ‘out in the open’. Thus, the term nāgad נגד has the adjectival and descriptive-verbal function of ‘(to be) conspicuous’ (cf. Arabic najd نجد ‘highland, plateau’). But it also carries the function of someone going out in front where he can be seen by everybody behind him. This is how you get nǝgad נגד ‘to lead’ in Hebrew, and nāgîd נגיד ‘leader’; Classical Syriac ngad ܢܓܕ ‘to go before’ and also nagoda ‘leader, chief’; and Arabic najuda نجد ‘(to be) brave’. The function extends into ‘bringing something to the fore’, ‘putting it out there’: this is how we get the associated verbal functions in Hebrew ‘to tell, to declare, to clarify, to make known, to publish’.

In the Tanakh, the way of ’Elyōn (Tian 天) is evident (xian 顯) because it is written. The same verb nāgad נגד can function as ‘to lead’, ‘to guide’, ‘to tell’ (Exo 4:28), ‘to show’, ‘to reveal’, ‘to declare’ (Psa 50:15), or ‘to publish’ (Ps 21:31)! The law of God is inscribed in the text—the God who does not show His face, even to Moses! It is the text itself which is left ‘conspicuous’ and ‘out in the open’!

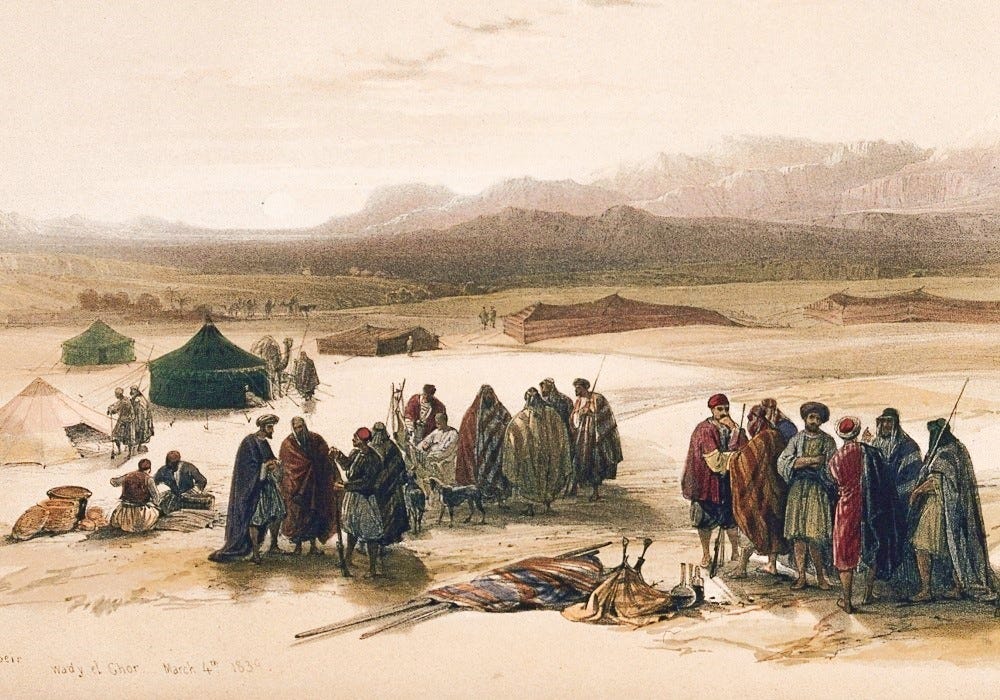

But here’s the proverbial catch. If we follow the text, then we ourselves are drawn out onto the najd نجد—the ‘highland’. We are drawn, or rather led (ngad ܢܓܕ). ‘out into the open’. And once we are there, we become ‘conspicuous’. The Hebrew people were led out of Egypt into the desert by Moses, who was led by ’Elohim. The desert, by the way, is desert. It is exposed. When we are given to hear the text which goes before us, we are exposed to it. The author of ‘Be Reverent’ got it right: 陟降厥士、日監在茲。 ‘It ascends and descends about our doings; it daily inspects us wherever we are’.

Being exposed like this is not a comfortable place for us human beings to be. We want safety, we want comfort, we want to be back in Egypt. We want our fleshpots and our bellies full of bread. We want to be told that we’re not accountable. In short: we grumble about where we are being led!

Because we are Westerners and because our minds have long been poisoned by Plato and Aristotle, the temptation of hiding ourselves from the text becomes significantly easier. We retreat inside our own minds where we are our own masters. We ignore things that are obvious (like a genocide committed with American bombs, livestreamed to the world on TikTok), and pretend things are obvious that actually aren’t (like that we, fundamentally decent people, stand for incontestable Good Things like ‘democracy’, ‘human rights’ and ‘freedom’). ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident,’ proclaims Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of independence… before rattling off a bunch of ‘self-evident truths’ that even he himself did not believe to be true! Otherwise, if ‘all men are created equal’, why would Thomas Jefferson claim ownership over human chattel? The Declaration of independence is merely the self-assertion of self-interested and self-aggrandising men, who do not even believe in the truth of what they assert. Paul—who, by the way, Jefferson famously detested—was clearly heard chuckling from his seventeen-hundred-year vantage point.

Paul was proclaiming a Tōrah תורה (an instruction) to a mixed Jewish and Gentile audience which sought a method of resisting the power and propaganda of Imperial Rome without violence. This method was already available to him in the Tanakh; he simply applied the same teaching to a different audience and different situations. For him and for that audience, the instructions are made manifest (higgîd הגיד) in the text. The obviousness of the text is not a matter for the Hellenised, Platonic-Aristotelian mind to contemplate. 無曰高高在上。 ‘Let me not say it is high and aloft above me!’ It is embedded in the text’s own syntax. The text, in turn, leads the hearer out into the open to where he is revealed, or exposed (yaggîd יגיד) to scrutiny by the text itself.

That scrutiny may be uncomfortable. It demands submission, which many of us instinctively avoid. But ultimately it is liberating.

It’s certainly more liberating than living back in Egypt—fleshpots or no fleshpots.