The lexicology of yi 義

‘And enter not into judgement with thy servant, for in thy sight shall no man living be justified.’ (Ps 142:2)

The Sinitic character yi 義 (simplified 义) is an incredibly important one in the Classics, and particularly in the Book of Rites, where it appears in over 200 separate instances. It continues to be an incredibly common character in modern Chinese, being the 208th most common character in the written language.

In modern vernacular Chinese, yi 義 appears in the compound words zhengyi 正义 ‘justice’; geyi 格义 ‘transcription of concepts’ (in Buddhism); qiyi 歧义 ‘ambiguous’; yanyi 演义 ‘historical drama’; yiqi 义气 ‘loyalty, brotherhood, fraternal spirit’; yiwu 义务 ‘duty’; yiyi 意义 ‘meaning’; and as the suffix -zhuyi -主义 ‘-ism’, as in gongchanzhuyi 共产主义 ‘communism’, minzhuzhuyi 民主主义 ‘democracy’, jihuizhuyi 机会主义 ‘opportunism’ or gudianzhuyi 古典主义 ‘classicism’.

The ideogram yi 義, typically glossed as ‘righteousness’, ‘justice’ or ‘right conduct’, depicts a sheep (yang 羊) on top of a weapon with a forked head (wo 我), which may have served as a phonetic element. One thing that Semitic and Sinitic cultures share is an association of ‘sheep’ with desirable traits and virtues. (Naturally the Semites of the Bronze Age did: sheep were their livelihood!) Sheep are herd animals. They naturally flock together. They will defend themselves and each other—particularly rams—with their horns, but they are not naturally aggressive. (Here is a link also to the xiezhi獬廌 or antelope, which the ancient Chinese knew to be related to sheep, and which was an ancient symbol of law.) Lambs kneel down at their mother’s teats to nurse: the ancient Chinese associated this behaviour with filial piety, xiao 孝. The lack of resistance to being led to slaughter (an alternate explanation for the forked-weapon wo 我 character element in yi 義) also led the Chinese to think of sheep as possessing a kind of noble selflessness. There is also evidence that the ancient Chinese found young lambs in particular aesthetically pleasing; hence the presence of a yang 羊 radical in the character mei 美 ‘beauty’. In the Classics, particularly in the Yijing, sheep (especially rams) are associated with headstrong stubbornness and rash action, but they also possess the ability to act correctly without being told:

九四:臀无膚,其行次且。牽羊悔亡,聞言不信。

其行次且,位不當也。聞言不信,聰不明也。The fourth NINE, undivided, shows one from whose buttocks the skin has been stripped, and who walks slowly and with difficulty. (If he could act) like. a sheep led (after its companions), occasion for repentance would disappear. But though he hear these words, he will not believe them.

‘He walks slowly and with difficulty:’ - he is not in the place appropriate to him. ‘He hears these words, but does not believe them:’ - he hears, but does not understand.

Book of Changes 《易經》, Guai ䷪夬 5

Cementing this semantic association with ‘sheep’, the Erya links the allied character yi 儀 ‘proper’, ‘right’, ‘polite’, ‘ceremony’, to other lexemes like xiang 祥, shan 善 and xian 鮮, all of which contain a semantic yang 羊, and all of which have highly positive connotations. Xiang 祥 carries the glosses of ‘lucky’ or ‘auspicious’, and is used in the modern compound jixiang 吉祥 ‘lucky’. Shan 善 carries the glosses of ‘good’, ‘noble’, ‘capable’, ‘competent’. And xian 鮮 carries the gloss of ‘fresh’, as in xinxian 新鲜. From the Erya we can clearly see how Sinitic lexemes like yi 義 tied to sheep tend to have connotations of worthiness, goodness and luck.

However, the term yi 義 in the Classics can be traced to the Ode ‘Vastness’ in the ‘Decade of Dang’. Intriguingly, this is one of the most straightforwardly wisdom-literary of the Odes, and is an imprecation of the later Yin Dynasty and its practices, in the name of the god of Yin (Shangdi 上帝). Observe how it is used:

蕩蕩上帝、下民之辟。

疾威上帝、其命多辟。

天生烝民、其命匪諶。

靡不有初、鮮克有終。文王曰咨、咨女殷商。

曾是彊禦、曾是掊克。

曾是在位、曾是在服。

天降慆德、女興是力。文王曰咨、咨女殷商。

而秉義類、彊禦多懟。

流言以對、寇攘式內。

侯作侯祝、靡屆靡究。How vast is God,

The ruler of men below!

How arrayed in terrors is God,

With many things irregular in His ordinations!

Heaven gave birth to the multitudes of the people,

But the nature it confers is not to be depended on.

All are [good] at first,

But few prove themselves to be so at the last.King Wen said, ‘Alas!

Alas! you [sovereign of] Yin-shang,

That you should have such violently oppressive ministers,

That you should have such extortionate exactors,

That you should have them in offices,

That you should have them in the conduct of affairs!

Heaven made them with their insolent dispositions,

But it is you who employ them, and give them strength.’King Wen said, ‘Alas!

Alas! you [sovereign of] Yin-shang,

You ought to employ such as are good,

But [you employ instead] violent oppressors, who cause many dissatisfactions.

They respond to you with baseless stories,

And [thus] robbers and thieves are in your court.

Thence come oaths and curses,

Without limit, without end.’Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Dang 蕩之什, ‘Vastness’ 蕩 1-3

So here in the Odes, we do not see this ‘goodness’, yi 義, among men: we only see its absence. We see only what it looks like when men without yi are elevated to positions of power. They are violent, oppressive, insolent, tellers of baseless stories, extortioners, robbers, thieves, revilers, cursing. King Wen’s complaint, in fact, is strikingly similar to David’s in Psalm 142:

ואל־תּבוא במשׁפּט את־עבדּך כּי לא־יצדּק לפניך כל־חי׃

כּי רדף אויב נפשׁי דּכּא לארץ חיּתי הושׁיבני במחשׁכּים כּמתי עולם׃

ותּתעטּף עלי רוּחי בּתוכי ישׁתּומם לבּי׃Enter not into judgment with thy servant; for no man living is righteous before thee.

For the enemy has pursued me; he has crushed my life to the ground; he has made me sit in darkness like those long dead.

Therefore my spirit faints within me; my heart within me is appalled. (Ps 142:1-3)

It is in fact a common complaint in the Hebrew Scriptures that no one is innocent (ṣadeq צדּק) before God. Before God, no one possesses truth (Arabic ṣadaqa صدق) on his side, no one is a friend (ṣadīq صديق) to truth. Understand that the Psalmist uses this root, which can mean ‘truth’ or ‘friend’, negatively with regard to man, after the invasion of Alexander and their enforced contact with the Hellenistic φιλόσοφος! (How could Alexander be said to love truth? By his actions, we can tell that he loved only power. And he was taught that love of power by Aristotle, who in turn learned it from Plato!) It is precisely man’s lack of friendship with truth, and especially these soi-disant ‘lovers of wisdom’, that Scripture is attacking in the Wisdom literature: just as the Odes are attacking the courtiers and advisers of the Shang and, by literary extension, those who hold power in the various states of the contemporary Zhou. The Odes themselves bear witness against Zhu Xi and those who followed him, just as Moses and the Psalmist bear witness against Philo of Alexandria and Josephus.

命之不易、無遏爾躬。

宣昭義問、有虞殷自天。

上天之載、無聲無臭。

儀刑文王、萬邦作孚。The appointment is not easily [preserved],

Do not cause your own extinction.

Display and make bright your righteousness and name,

And look at [the fate of] Yin in the light of Heaven.

The doings of High Heaven,

Have neither sound nor smell.

Take your pattern from king Wen,

And the myriad regions will repose confidence in you.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Wen Wang 文王之什, ‘Wen Wang’ 文王 7

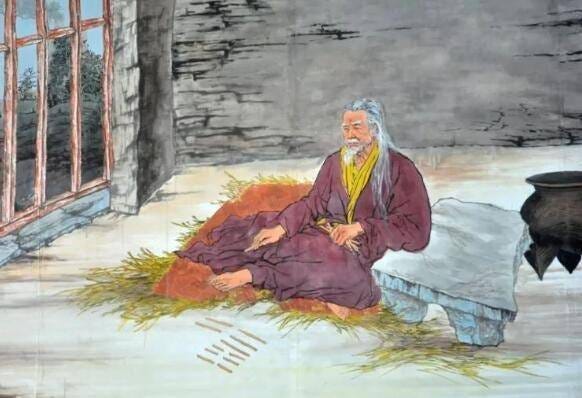

This Ode is in fact a warning to the human being. If you go around trumpeting your own horn, you will fall just as the wicked King Zhou of Shang fell—because the ways of High Heaven are not your ways, O human; and the thoughts of Heaven are not your thoughts. You cannot hear and you cannot smell them. And what is the ‘pattern’ (xing 刑) of Wen of Zhou, that is so ‘righteous’ (yi 儀)? He was slandered, taken as guilty, cast into the dungeons of Youli and (in some versions of the story) force-fed the meat of his own slaughtered first-born son by King Zhou of Shang. The last part may in fact be a fictional bit of apocrypha. However, it is clear from the Odes that Wen of Zhou was subjected to the utmost, most abject humiliation, torture and grief by his enemy, yet he bore through this ill-treatment with submission to Heaven.

Yi 義 thus has inescapably a sacrificial, even self-sacrificial, connotation. Like ṣadeq צדּק, yi 義 is innocence and purity and truth. But, also like ṣadeq צדּק if we are counting Isaac the son of Abraham as ‘righteous’ (Qur’an 37:112), it is the innocence and purity of a slaughtered lamb. Thus, it is not surprising that the Odes account this quality as so rare, even next to nonexistent among human beings! What human being would willingly undergo such privations as King Wen did? No one would. This is why the Odes (see ‘Vastness’ above) say that those who are ‘good’, or ‘righteous’ (yi 義) turn out to be so ‘few’ (xian 鮮)!

This is because the Odes are wisdom literature. The Odes were compiled, if not written outright, at a time when the polity of Zhou was falling down spectacularly around everyone’s ears. The various Central States were ruled by greedy, self-interested, power-mongering warlords. Part of the message of the Odes, is simply to say that this state of affairs is nothing new. Even in the Bronze Age, turmoil, backstabbing, power games and tyranny were already literally as old as dust. The Yin (Shang), and the Xia before the Yin, both decayed and fell to the same political weakness. The strong implication of the Classics is that the Zhou would inevitably do the same.

And the one chosen to be the voice of this body of scripture, Confucius, is himself of the royal dynasty of the Shang. This is yet another literary device. Confucius’s royal ancestry is asserted not to bolster any political claim on his behalf, because he never sought to be crowned king. Instead it serves as a cautionary tale. Confucius self-avowedly comes from the same lineage, the same accursed blood as the evil Shang Zhou Xin. Yet only he is worthy to prophesy in the name of Tian 天 against his own generation! A generation which, in turning away from the yi 義 of the Wen Wang who deposed Confucius’s ancestor, is making the same mistakes as the Shang.

:ואין כּל־חדשׁ תּחת השּׁמשׁ

And there is nothing new under the sun! (Ecclesiastes 1:9)

It is refreshing in a certain way, to see that the Odes and the Psalms, in slightly different ways, end up saying things very closely in parallel. They belittle us human beings. They refuse to take us seriously. Only the one God is righteous and we cannot understand Him, Whose doings have no sound we can hear and no odour we can smell. (On the contrary, the Ode implies in its phrasing—chou 臭—that we’re the ones who ‘stink’!)

So, if you’re bummed about the election results—and honestly, why not?—try to remember the Odes, and the Book of Ecclesiastes. America is not righteous. America is a nation like any other, governed by princes like any other, and we aren’t any kind of novelty item: no, not even in our sins, though our sins against God and His Law are plenty. Just ask the Gazans! We will fall, deservedly, just like any other empire. But take heart: there is always the wisdom. There are always the Psalms, and the Proverbs, and the Book of Ecclesiastes!