The lexicology of nan 難

Thou hast shewn thy people hard things; thou hast made us drink the wine of astonishment. (Ps 59:3)

The Sinitic character nan 難 is the 295th most common character in the written Chinese language. It carries the basic glosses of ‘hard(ship)’, ‘difficult(y)’, ‘sad(ness)’, ‘ill(ness)’, ‘distress’ and ‘disaster’. It is basic vocabulary which is shared across the Sinitic language family, with cognates in Tibetan (mnar མནར ‘suffering’, na ན ‘to be sick’, nad ནད ‘disease’, nan te ནན་ཏེ ‘sick, ill’) and Myanma (na နာ ‘to suffer pain or illness’, nat နတ် ‘ancestral spirit’).

In modern Chinese, the character nan 難 (simplified 难), is most commonly glossed as ‘difficult’ or ‘hard’. It is used in compound words like diaonan 刁难 ‘to make trouble (for someone)’; kunnan 困难 ‘difficulty’; nandian 难点 ‘pain point’; nanguo 难过 ‘sad’; nanren 难忍 ‘unbearable, intolerable’; nanse 难色 ‘(an expression of) reluctance’; nanti 难题 ‘difficult problem’; nanyi 难易 ‘difficulty level’; weinan 为难 ‘embarrassing situation’; zunan 阻难 ‘to thwart, to obstruct’. It is also used in common phrases expressing something unpleasant to the senses: nanchi 难吃 ‘unappetising’; nankan 难看 ‘ugly’; nanting 难听 ‘noisy’; nanwen 难闻 ‘stinky’.

Its usage in Classical times was not that different. It certainly glosses the function of ‘difficult’, as in the Daodejing:

天下皆知美之為美,斯惡已。皆知善之為善,斯不善已。故有無相生,難易相成。。。

All in the world know the beauty of the beautiful, and in doing this they have (the idea of) what ugliness is; they all know the skill of the skilful, and in doing this they have (the idea of) what the want of skill is. So it is that existence and non-existence give birth the one to (the idea of) the other; that difficulty and ease produce the one (the idea of) the other…

Daodejing 《道德經》 2

However, it also has a broader set of glosses than the modern Chinese usage permits. For example, it can mean ‘to blame’, ‘to reject’ or ‘to censure’, as in the Book of Documents:

柔遠能邇,惇德允元,而難任人,蠻夷率服。

Be kind to the distant, and cultivate the ability of the near. Give honour to the virtuous, and your confidence to the good, while you discountenance the artful – so shall the barbarous tribes lead on one another to make their submission.

Book of Documents 《尚書》, Canon of Shun 舜典 8

It could also carry the gloss, similar to the modern function of nanti 难题, of a ‘debate’ or a ‘point of disputation’. As a verb, it could also mean ‘to resent’, ‘to hate’, ‘to fear’. As an abstract noun, pronounced nuo, it was used to describe a ceremony for banishing evil spirits responsible for disease and crop failure.

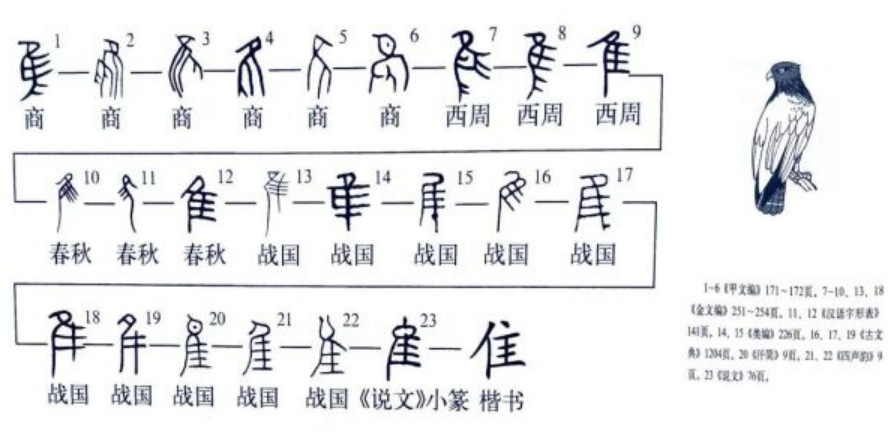

According to the Shuowen jiezi, nan 難 was originally written as 𩁬. It consists of a phonetic component han 堇 (modern 暵) ‘dry’ or ‘hot’, and a semantic component zhui 隹 ‘short-tailed bird’. The usage of this last component in a character meaning ‘hardship’ is obscure, but a strong hint as to the possible ancient semantic connotation of zhui 隹 in this character is found in the Mozi:

且《周書》獨鬼,而《商書》不鬼,則未足以為法也。然則姑嘗上觀乎商書,曰:『嗚呼!古者有夏,方未有禍之時,百獸貞蟲,允及飛鳥,莫不比方。矧隹人面,胡敢異心?山川鬼神,亦莫敢不寧。若能共允,隹天下之合,下土之葆』。察山川鬼神之所以莫敢不寧者,以佐謀禹也。此吾所以知商書之鬼也。

If there are testimonies only in the books of Zhou and none in those of Shang still it could not be reliable. But we find among the books of Shang the following: ‘Oh! Anciently, before Xia was visited by misfortune, of the various animals and insects and even birds none deviated from their proper course. As to those who have faces of men, who dare be divergent in heart? Even the hills and rivers ghosts and spirits dared not be insurgent.’ If one is respectful and sincere one could maintain harmony in the world and stability to the lower earth. Now it was to assist Yu that hills and rivers ghosts and spirits dared not be insurgent. Here we have a testimony of ghosts in the book of Shang.

Mozi 《墨子》, ‘On Ghosts III’ 明鬼下 14

Here we see another concrete attested linkage in Classical-era literature between the semantic component zhui 隹 and the concept of nat နတ် in traditional Myanma culture. Birds with human faces (zhui ren mian 隹人面) were thought to be supernatural in origin: evil omens or signs of impending doom. In addition, certain avian behaviours—particularly swarms of small birds (zhui 隹 refers specifically to a passerine or a small bird)—had negative connotations to agricultural peoples in antiquity because they were thought to eat seedlings, cut off heads of grain and ruin crops, leaving only stubble. The Erya links such small birds directly to the eating of oats (qu蘥) and other forms of edible grass (yan萒). Also, in one particular place where sparrows appear in the Odes, they are specifically cited as a nuisance comparable to an unwanted suitor:

誰謂雀無角、何以穿我屋。

誰謂女無家、何以速我獄。

雖速我獄、室家不足。Who can say the sparrow has no horn?

How else could it bore through my house?

Who can say that you did not get me betrothed?

How else could you have urged on this trial?

But though you have forced me to trial,

Your ceremonies for betrothal were not sufficient.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Shao and the South 南召, ‘Road Dew’ 行露 2

This partway-true folk belief in passerines and other small birds being harmful to crops was widespread. In fact, it served as one of the rationales behind the inclusion of sparrows in the chu si hai 除四害 pest-killing campaign of Communist China in the 1950s. However, this campaign itself resulted in an ecological disaster after the sparrow population plummeted, allowing locusts and other actually harmful pests to reproduce unchecked. But such beliefs were in fact widespread across ancient Bronze Age societies in Asia. In ancient West Asia, falcons were domesticated by farmers in part to keep down populations of starlings, pigeons and passerines which damaged crops by feeding on seeds and seedlings.

This brings me to the Semitic word qaš קש ‘stubble, chaff’.

Fr Paul Tarazi explained to me two days ago that this biliteral word is in fact a predecessor linked to a host of semantically-related triliterals. For example: qāšaš קשש ‘to gather stubble’; qāšê קשה ‘hard, severe’, qǝšey קשי ‘stubbornness’, qāšaḥ קשח ‘to harden, to firm up’, qāšar קשר ‘to bind, to confine, to force, to conspire’, qešet קשת ‘a bow’ (a branch ‘bound’ or ‘shortened’ to form a weapon) or ‘bowman’. It is further related to other words formed from the biliteral q-ṣ קץ ‘end’: used in qāṣâ קצה ‘end’, qāṣô קצו ‘boundary’, qāṣab קצב ‘to chop, to mince’, qāṣaṣ קצץ ‘to cut off’, qǝṣāf קצף (Arabic qaṣafa قصف) ‘to break, to snap off, to be wroth (with)’, the familiar qāṣer קצר (in Arabic qaṣīr قصير) ‘short’, qāṣar קצר and qāṣîr קציר ‘to reap, to harvest, crop’. This biliteral root is the origin of the Latin botanical genus name Cassia (a type of cinnamon, qǝṣī‘â קציעה, whose bark is cut fine to produce the spice!), and the same root figures in the Semitic word for ‘story’ (Arabic qiṣṣa قصّة), which is cut out of a larger narrative and given an ending!

But it can be seen with ease how the functions of ‘hardness’, ‘severity’, ‘cruelty’ or ‘hardness of heart’ being linked semantically to the harvest and to the stubble, what is left when the plant is cut, is directly linked to the Chinese term which glosses ‘hardness’: nan 難. Nan 難 is what happens to the people when the sparrows get to the harvest first, and leave them the qaš קש, the chaff!

In the first book of Scripture, hardship (different root here: ‘iṣṣābôn עצבון ‘pain, toil’ from ‘āṣab עצב ‘pain, vexation, nervous reaction’, but the same functionality) is linked directly to agriculture through the curse on the ground incurred by the disobedience of Adam and Eve to the first command of God (Gen 3:17), and again upon Cain the agriculturalist through his murder of his brother the shepherd (Gen 4:11).

The authors of Scripture were remarkably clever this way. They understood quite well, that much of the hardship that we incur is in fact self-inflicted, and they told a qiṣṣa قصّة set in the region of the Four Rivers to explain why that is. It isn’t that the ’Elohim of Genesis chapter 3 is being arbitrary! (Well, maybe He is, a little bit.) But think: Chinese peasants thought it was completely reasonable to kill off sparrows by the millions… until the locusts started showing up. The fact that the human beings suffer a reaction from the ground, for eating a fruit (a product of the ground) that they weren’t allowed to touch, is a way of describing how we suffer unforeseen consequences for our disobedience to God’s law, that appear logical only in hindsight.