The lexicology of ren 人

What is man that thou art mindful of him, and the son of man that thou dost care for him? (Psalm 8:5)

At the Academy Awards in 2021, the award for Best Director went to Chinese-expatriate filmmaker Chloé Zhao. Upon receiving the award, Chloé Zhao recited to the academy the first two lines of the Sanzijing 《三字經》 or Three-Character Classic: Ren zhi chu, xing ben shan… 人之初,性本善… ‘People, at birth, are inherently good.’ The Three-Character Classic, written in the thirteenth century by Wang Yinglin 王应麟 (1223 – 1296 AD) is broadly considered to be a masterly philosophical distillation of the Neo-Confucian orthodoxy that arose in the Tang and was ascendant in the Song and Ming Dynasties—and is often memorised by young Chinese children as part of their early cultural education. It was considered a necessary building-block for the acquisition of such necessary virtues as filial piety (xiao 孝), integrity (cheng 诚) and human-kindness (ren 仁).

But there is a slight problem. The Sanzijing 三字經 is unfortunately not the faithful and filial and humane summation of the doctrines of Confucius that it purports to be. In fact, something very close to the opposite is the case.

Confucius, or Master Kong 孔子, as part of the school which produced the Five Classics, did not begin with the ren 人, the human being. He began with the doves—or the ‘ospreys’, rather, if you rely on Legge’s translation of jiu 鸠. If the school which produced the Classics, of which Confucius was a member, had wished to assert the inherent goodness of man, they would have left aside the Odes and begun their canon with the Documents: the political-literary production of the human kingdoms which exerted their mastery over the Central States. The Odes, after all, take a decidedly dimmer view of the human being and of human affairs in general than the Three-Character Classic does, or the neo-Confucian philosophers who produced it. This is actually one of my favourite Odes, because it encapsulates so well the teaching of the Odes on the nature of the human being:

相鼠有皮、人而無儀。

人而無儀、不死何為。相鼠有齒、人而無止。

人而無止、不死何俟。相鼠有體、人而無禮。

人而無禮、胡不遄死。Look at a rat, – it has its skin;

But a man should be without dignity of demeanour.

If a man have no dignity of demeanour,

What should he but die?Look at a rat, – it has its teeth;

But a man shall be without any right deportment.

If a man have not right deportment,

What should he wait for but death?Look at a rat, – it has its limbs;

But a man shall be without any rules of propriety.

If a man observe no rules of propriety,

Why does he not quickly die?Book of Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Yong 鄘風, ‘Look at a Rat’ 相鼠

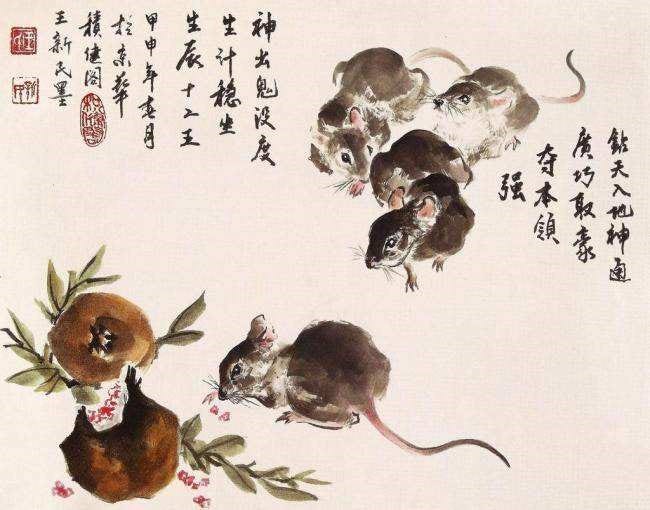

Think about the image that rats commonly present in Western culture. We see them as disease-bearing, thieving, scrounging vermin. In Chinese culture, this wasn’t necessarily the case. The image of rats in Chinese culture was complex: even though they were indeed associated with hoarding and greed (no farmer likes to see rats around his food stores!), rats were nonetheless also respected as consummate survivors. The rat is the first of the traditional Chinese zodiac signs, and its position in that role was often attributed to its cleverness. But the comment that the Ode is making is on the deficiency of human nature! Man is not a natural bearer of righteousness or self-limitation or propriety—yet these things are necessary for him to survive.

The character ren 人 is one of the most basic and prolific lexemes in Chinese of any era. It is the 7th most common character in the written language. It is one of the primeval pictographs (xiangxing 象形) that has survived in more or less unaltered form in Chinese from the earliest Shang oracle-bone inscriptions: an upright human-shaped figure with legs. The most likely etymology derives it from the same source as the lexeme er 爾, which represents a proto-Sinitic lexeme *nyɨy ‘near’ (reflected in Tibetan nye ཉེ and Burmese ni: နီး, both functioning as the adjective ‘near’), nominalised by a final *-n, rendering *nyɨn ‘one who is near’ (making ren 人 a cognate to Tibetan nyen ཉེན ‘relative, kinsman’).

In modern form, ren 人 can function as ‘person, human being, man’ as in nüren 女人 ‘woman’; nanren 男人 ‘man’; gongren 工人 ‘artisan, labourer’; nongren 弄人 ‘peasant, farmer’; shiren 诗人 ‘poet’; fuzeren 负责人 ‘the one in charge’; bingren 病人 ‘sick person, invalid’; or diren 敌人 ‘enemy’. It can also serve in the nominal function as ‘people’ or ‘group’ or ‘humanity’ in general, as in jiaren 家人 ‘household’; renyuan 人员 ‘staff’; laoren 老人 ‘the elderly (as a group)’; renmin 人民 ‘the people’; or renlei 人类 ‘humanity’. Or it can serve pronominally as ‘one’ or ‘someone’: youren 有人 ‘someone’; taren 他人 ‘someone else’; bieren 别人 ‘others’; or yigeren 一个人 ‘by oneself’. It can even function as ‘me’, as in zhen fan ren 真烦人 ‘it really annoys me’. Or it can function as ‘body’, as in renshen 人身 ‘the body’; or rensheng 人生 ‘(biological human) life’. An additional function which has been passed down from classical use is rencai 人才 ‘talent, genius’.

In Classical Chinese, ren 人 had much of the same lexical range as in modern Chinese. Ren 人 could refer to a ‘person’: 乃如之人兮、逝不古處。 ‘Here is the man who treats me not according to the ancient rule.’ (Book of Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Bei 邶風, ‘O Sun, O Moon’ 日月 1) It could also refer pronominally to ‘others’: 禮,不妄說人,不辭費。 ‘According to those rules, one should not (seek to) please others in an improper way, nor be lavish of his words.’ (Book of Rites 《禮記》 1.7) It could refer to ‘people’ or ‘humanity’ in general: 許人尤之、眾穉且狂。 ‘The people of Xu blame me, but they are all childish and hasty.’ (Book of Odes 《詩經》, Odes of Yong 鄘風, ‘Galloping Steeds’ 載馳 3) This is also attested in the Erya 《爾雅》, which links ren 人 to shi 師 and shu 庶, both functioning as ‘masses’ or ‘multitudes’.

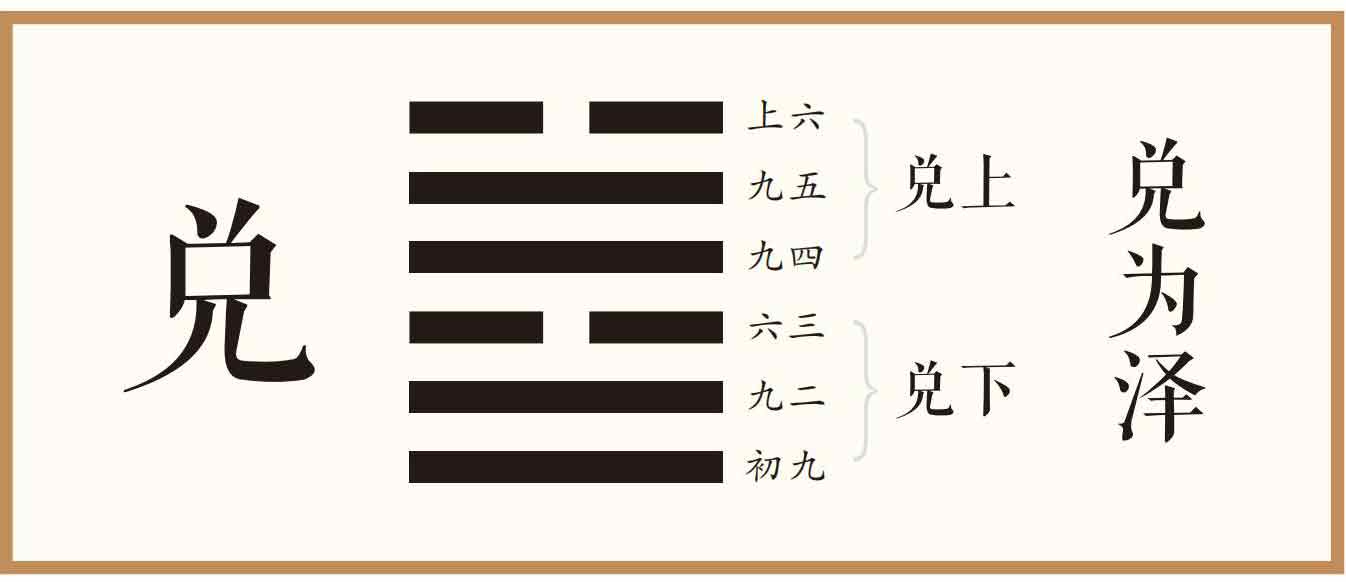

Ren 人 could also refer, as mentioned above, to a person’s ‘talent’: 與人不求備 ‘he allowed (the good qualities of) the men (whom he employed), and did not seek that they should have every talent’ (Book of Documents 《尚書》, Yi’s Instructions 伊訓 1). It could also refer to a person’s character: 任官惟賢材,左右惟其人。 ‘Let the officers whom you employ be men of virtue and ability, and let the ministers about you be the right men.’ (Book of Documents 《尚書》, Common Possession of Pure Virtue 咸有一德 1) And it could refer to the ‘affairs’, the ‘business’ or ‘concerns’ of humanity: 是以順乎天,而應乎人。 ‘Through this there will be found an accordance with (the will of) heaven, and a correspondence with (the feelings of) men.’ (Book of Changes 《易經》, Dui ䷹兌 1).

The obvious parallel to draw here would be with the Hebrew hā’Ādām האדם, which is the term for ‘the human being’ in the Tanakh. The early Semitic root from which this term comes, ’-d-m א-ד-ם or أ د م, carries the basic function of a colour or a dye: ‘red’ (as in Akkadian ’adamātu 𒀀𒁕𒈠𒌈 and Ugaritic ảdm 𐎀𐎄𐎎 ‘red ochre’, ‘hematite’, ‘ferrous clay’, ‘red dye’). The connexion with the human being may be through the function of ‘(red) blood’, which in Aramaic and Classical Syriac is ’ǝdem ܐܕܡ or (by consonantal substitution) dǝm’ā ܕܡܐ, a doublet of ’ādām ܐܕܡ ‘the human being, Adam’ (same consonants). Even in Qur’ānic Arabic, the word for ‘blood’ is readily attested as dam دم, which has a doublet in the verb for ‘to paint, to daub, to dye’, damm(a) دمّ! Of course, in the Tanakh itself, the first human being is formed out of this ferrous clay, similar to how an idol would be shaped. ויּיצר יהוה אלהים את־האדם עפר מן־האדמה ‘then the Lord God formed man (hā’Ādām) of dust from the ground (hā’adāmâ)’—but then God breathes life into the clay figure: ויּפּח בּאפּיו נשׁמת חיּים ויהי האדם לנפשׁ חיּה ‘and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being’ (Gen 2:7).

The first part of this verse, I note, is a direct attack on Plato. And the second part of this verse is a direct attack against Plato’s student, Aristotle. In the Republic, Plato’s Socrates posits a myth in the city-in-speech that ho Theos ο Θεος alloyed the souls of its people with some sort of refined metal: whether gold for the rulers; silver for the auxiliaries or guardians; or brass or iron for the common craftsmen and servants (Πολιτεια 3.415a-d). This myth of the metals would determine the ideal function of a person in a just city where each man works his own proper business. The authors of Genesis directly attack Plato’s myth of human sortation with a countervailing myth of human commonality: that the souls of all human beings are made, not out of any refined metal, not even out of smelted iron, but out of hematite-bearing earth, the most mundane stuff imaginable.

The second part of this verse’s attack on Aristotle is slightly more subtle… but only slightly. Aristotle vaunts the human being to a superior status over all the other animals, by virtue of his having been designed upright and bipedal, in a pleasing and correct way in accordance with a universal divine pattern. Likewise (though acknowledging the obvious superiority of other animals’ senses of sight, hearing and smell), he praises the subtlety and refinement of the human sense of touch and of the human palate as being evidence of human superiority over the beasts (Των περι τα ζωα ιστοριων 1.493a-b). Genesis attacks this entire conception, but in order to understand how we need to examine the Semitic text closely. The human being, haven been fashioned like a clay idol (of the sort which is painted, that is damma دمّ) without sense or speech or reason, is given life by God’s breath, and becomes a nefeš ḥayyâ נפש חיה, literally a ‘living breather’. But what is a nefeš ḥayyâ? It is the same lexical construct that is used to describe the living inhabitants of the sea, air and land that were made before people (Gen 1:20-1; Gen 1:24; Gen 2:19). Man’s senses do not render him superior; rather in literally breathing sense into him, God elevates him to the same living status as the rest of the animals!

I argue that the Sinitic Five Classics likewise make a sally against the anthropocentrism of the official ideology of the Zhou Dynasty. It is worth remembering, when reading the Classics, the preference for canonical order (xu 序) and insistence on zhengming 正名 ‘correct nominalisation’, by the one man who signed his name to the Classics—Confucius. The primacy of the Odes within the Classical canon is insisted upon at multiple points in the Analects (Lunyu 《論語》 1.15, 3.8, 7.18, 8.8, 16.13, 17.9). And unlike later texts like the Mencius and the Three-Character Classic which return to a stance of anthropocentrism, the Odes do not begin with the ren 人, but instead with the jiu 鸠! And the Odes indeed begin by praising the jiu 鸠 for its modesty, its constancy and its affection toward its mate!

I am indebted to James Legge for many reasons—don’t get me wrong. His dedication to translating the Five Classics into English for foreign audiences to read is truly awe-inspiring. His clear love and admiration for the culture which produced them, likewise are nothing but admirable. (And I’m sensitive to the pitfalls of chronological snobbery: much as I rag on Victorian Britons like Legge for being ruthless imperialists, it really isn’t like we modern Westerners are empirically any better than they were.) And of course Legge’s works have the singular virtue of being in the public domain for all to read and cite freely! But here, his translation of jiu 鸠 as ‘ospreys’ really causes me to raise an eyebrow—especially because Legge himself does not hesitate to translate the same character as ‘dove’ elsewhere, even in later Odes. The jiu 鸠 is in fact simply a common pigeon. Think about how New Yorkers treat pigeons, and the attitude of the Odes toward animals like pigeons and rats, particularly when they are favourably compared to human beings, becomes far clearer!

Similarly to how Plato and Aristotle elevated Hellenes above barbarians and human beings above animals, the official Zhou Dynasty’s ideology elevated the huaren 华人 ‘people of the Pattern’ above the siyi 四夷, the ‘strangely-clad people of the four cardinal directions’, whose lack of culture and self-control made them akin to qinshou 禽兽 ‘birds and beasts’. Just as the Tanakh attacks the Platonic-Aristotelian hierarchy and the ‘great chain of being’ by placing man last among the tôlǝdôt of the heavens and the earth, the Odes deliberately overturn this ideological Zhou hierarchy and stand it on its head. It is the pattern of birds like the jiu 鸠 ‘pigeon’ and beasts like the shu 鼠 ‘rat’ that is considered virtuous, while the way of the Zhou and especially the wangshi 王事 ‘business of kings’, often perverts or distracts the people from their proper duties and affections.

~~~

Here I am going to make a slight detour in discussion and return us to considering Bishop Aluoben’s seventh-century introduction of the themes of the Tanakh into Chinese in the Xuting Mishisuo jing. His usage of the terms zhufo ji feiren 诸佛及非人, literally ‘all the Buddhas and non-humans’, make clear that he is offering a framework for his Chinese audience’s consideration that fits within expectations of a Buddhist intellectual context. Feiren 非人 was the term often used within contemporary Buddhist cosmology for the kinnara किन्नर: a dhamma-following heavenly being, often represented as part-human and part-animal (usually a bird) which is associated with transcendant heavenly music and art. His invocation of ‘all the Buddhas’ (zhufo 诸佛 paralleling the Classical compound zhuhou 诸侯 ‘all the feudal lords’) and the heavenly choir of the kinnarāsa (feiren 非人) are part of Bishop Aluoben’s effort to communicate to the Tang Chinese the concept of the kol-ṣābā’a כל-צבא that attend and wait on ’Elôhîm. As we shall see, he elaborates on that further with several additional concepts from Buddhist cosmology.