The lexicology of qi 其 and zhi 之

Ahh, pronouns.

Pronouns have become, in present-day America, a needlessly-politicised part of speech. In certain circles, giving one’s pronouns (‘he/him’, ‘she/her’) has become something of a political ritual. It is a low-cost way of signalling one’s ‘ally’-status with transgender people, or one’s status as a ‘good’ person among a certain segment of the symbolic-capitalist elite.

Turning pronouns into a political weapon was bound to produce a Newtonian reaction. Thus, predictably, there has been an equally-stupid culture-war conservative backlash against the entire concept of pronouns in general. Obviously, pronouns are a simple grammatical necessity in English, as gets inevitably pointed out by wags on social media.

(Personally, in practice, I’m a fan of simply calling people what they want to be called. I have no desire to control anybody. For the Orthodox, I draw the line at the question of what name you go by at the chalice; that is because we acknowledge only one baptism. And St Paul also advises people to ‘stay as you are’. That admonition does not only apply to virgins and married people.)

The problem is that this is all a highly Anglocentric and Eurocentric debate in the first place.

And this problem for all intents and purposes simply doesn’t exist in spoken Mandarin. The only verbal third-person pronoun is ‘ta’; though this can be written different ways in Chinese script depending on the gender or the status of the person in question. So you have ta 他 ‘he / him’; ta 她 ‘she / her’; ta 它 ‘it’ (for inanimate objects, never for people); ta 牠 ‘it’ (for animals); ta 祂 ‘He / Him’ (for God)—all pronounced the same way. There was a colonialist-imperialist attempt among British-manipulated Hong Kong student activists to introduce a new character, ‘X也’, as a gender-neutral ta, but this (thankfully for Chinese speakers everywhere) never took off.

Classical Chinese is an almost completely gender-neutral language, at least in terms of its grammar. The character qi 其 functioned as the second most common third-person personal pronoun in Classical Chinese after zhi 之, and both were completely gender-neutral. Either could refer to ‘he’, or ‘her’, or ‘it’, as grammatical object. There being no nominative third-person pronoun in Classical Chinese, the difference is that zhi 之 was largely used in accusative function, as ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘it’ or ‘them’; while qi 其 was possessive or genitive: ‘his’, ‘her’, ‘its’ or ‘their’.

These characters have a similar ‘archaic’ sound to them in modern Chinese as he 何, but they are still in very common use. Qi 其 is still the 85th most-common character in written Chinese, and zhi 之, the 44th. Zhi is used in very common expressions, like baifenzhi 百分之 ‘percent’, or in fact any fraction: ‘one-quarter’ in modern Mandarin is sifenzhiyi 四分之一. It’s often used as a synonym for de 的 ‘of, possessive particle, prepositional particle’ in set phrases like zhihou 之后 ‘after (that)’; zhiqian 之前 ‘before (that)’; zhizhong 之中 or zhinei 之内 ‘inside (of)’; zhijian 之间 ‘between (those)’; zhiwai 之外 ‘outside (of)’; fanzhi 反之 ‘conversely’; and zhilei 之类 ‘et cetera’. Qi 其 is also used in numerous modern Mandarin compounds: most notably qita 其他 or 其它 ‘(an)other’; but also qishi 其实 ‘in fact’; youqi(shi) 尤其(是) ‘especially’; jiqi 及其 ‘also’; qici 其次 or qihou 其后 ‘the next’ (in a series); qiyu 其余 ‘the remainder, the rest of’; and yuqi 与其 ‘rather than’.

Qi 其 is also used in numerous four-character idiomatic compounds, like budeqifa 不得其法 ‘to not know the right way’; kuadaqici 夸大其词 ‘to exaggerate’; shunqiziran 顺其自然 ‘let nature take its course’; momingqimiao 莫名其妙 ‘inexplicable, baffling, beyond description’; mingfuqishi 名副其实 ‘befitting the name, living up to the name’; turuqilai 突如其来 ‘to suddenly come up’; ruowuqishi 若无其事 ‘nonchalantly’; and chuqibuyi 出其不意 ‘to catch someone off guard; to land an unexpected stroke’.

Qi 其 is what Xu Shen in Shuowen jiezi 《説文解字》 describes as a loangraph (jiajie 假借). That is: it’s a character that originally carried a different function but was borrowed for another, on account of phonetic similarity. Its origin was as a pictogram of a ‘basket’ or a ‘fan’ such as would be used for winnowing grain. This function is currently held by the modern character ji 箕, which is the same character qi 其 clarified by a bamboo (zhu 竹) radical, in a similar way to how yun 雲 functions in ‘traditional’ Chinese in place of yun 云 for ‘cloud’. Zhi 之 functions also as a pictogram and a loangraph. I have mentioned before that this zhi 之 carried an original function of ‘to go’ or ‘to start’, being the graphical representation of a foot (zhi 止) over a starting-line (yi 一). It was apparently also adapted from this function as a loangraph for the general third-person pronoun, again, on account of its phonetic similarity to the spoken word.

By contrast, Semitic languages all have a robust two-gender grammatical morphology. Arabic has huwa هو ‘he’ and hiya هي ‘she’. Syriac has huw ܗܘ ‘he’ and hay ܗܝ ‘she’. Hebrew has hū’ הוא ‘he’ and hī’ היא ‘she’. Ge’ez has wǝ’tu ውእቱ ‘he’ and yǝ’ti ይእቲ ‘she’. These are all descended from a proto-Semitic root reflected in the Akkadian šū ‘he’ and šī ‘she’. But, similarly to Spanish or Portuguese, there is no non-gendered ‘it’ or ‘they’ pronoun in the Semitic languages (though in modern Hebrew at least, there have been politically-motivated attempts to create one, similar to modern Chinese). Clearly this is one autochthonic difference that distinguishes West Asian languages from East Asian ones… and it runs straight against, shall we say, the ‘stronger’ forms of Lacouperie’s theory. But what actually interests me more is actually the use of loangraphic constructions to show the pronoun in written language, and what this implies for comparative study of Sinitic and Semitic languages.

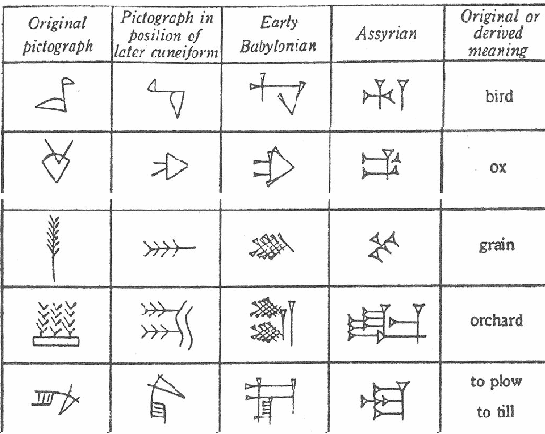

In Akkadian, both masculine and feminine third-person singular pronouns šū and šī are represented by a logogram borrowed from Sumerian: bi 𒁉, which evidently had something to do with ‘distribution’ or ‘gift’, and evidently also had something to do with ‘beer’ (as the same logogram was used in Sumerian to represent kaš ‘beer’). Sumerian logograms were originally pictograms, similar in many respects to Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs and, in fact, a certain set of oracle-bone script Chinese characters. They represented discrete concepts, objects or ideas. But the adoption of these pictograms into other languages, as Akkadian clearly adopted Sumerian, show how they were adaptable to multiple linguistic contexts.

But in Egypt, hieroglyphs quickly adapted to phonetic, syllabic functions. That is: they began to represent sounds, not discrete concepts. The same thing happened with Semitic languages like Akkadian: logographic symbols began to be used phonetically.

In Chinese, this process of evolution from pictograms to phonetic symbols happened more slowly and more gradually. You have instances of loangraphs like qi 其 (a pictogram representing a basket) and zhi 之 (a pictogram representing a foot over a starting line) coming to represent abstract pronouns like ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘they’ and ‘it’ that were pronounced the same way as qi and zhi. This is an intermediate step in that evolution. But Chinese never needed to make the transition to being fully phonetic the way the West Asian languages did. Instead it adopted a kind of ‘rebus principle’, whereby a phonetic element was added to an existing character, a ‘sounds-like’ component, to produce a phono-semantic glyph. This is the way that the great majority (upwards of 80%) of most modern Chinese characters work. You have one side of a character, usually the ‘radical’, that represents the semantic function; the other side that represents a pronunciation guide, a ‘sounds-like’. That’s how you get characters like:

Zhong 鍾 ‘clock’: from semantic jin 金 ‘gold, metal’; sounds like zhong 重 ‘heavy’

Hui 煇 ‘brilliance, splendour’: from semantic huo 火 ‘fire’; used to sound like jun 軍 ‘army’

Song 松 ‘pine tree’: from semantic mu 木 ‘wood, tree’; sounds like gong 公 ‘public, common’

Liu 流 ‘to flow’: from semantic shui 水 ‘water’; sounds like yu 育 ‘newborn baby’

Bi 壁 ‘wall’: from semantic tu 土 ‘earth’; sounds like bi 辟 ‘to rule, to govern, monarch’

The interesting question is: why? Why did Chinese evolve this way, and the Afro-Asiatic languages (like Egyptian, Akkadian, Arabic, Syriac, Hebrew and Ge’ez) evolve in a fully-phonetic direction, with pictographic symbols being converted entirely into sound-values, and then reconfigured into cross-functional biliteral and triliteral roots?

All of these writing-systems were created on civilisations based on river systems. The Nile gave rise to Egyptian. The Tigris and Euphrates gave rise to the Semitic languages. And the Huanghe and Changjiang gave rise to the Sinitic languages. All of these writing systems were functionally elitist in orientation. Writing was the function of an elite priestly caste in each case: that’s why they were called hieroglyphs. In China, the privilege of marking oracle bones was accorded to an elite class of diviners, who were almost always part of the Shang royal family. In Egypt, it was the priests in particular who were in charge of writing, and the ability to read and write was a marker of elite status enjoyed in antiquity by no more than ten percent of the Egyptian population at most. The same was the case, albeit to a lesser degree, in the Fertile Crescent. In ancient Mesopotamia, the largest number of inscriptions we have are religious and political in nature, and those who inscribed them were almost certainly members of the religious-political (amelu) elite. Scribes were educated in temples. However, it seems that merchants (mushkina) quickly picked up on the usefulness of writing for conducting transactions.

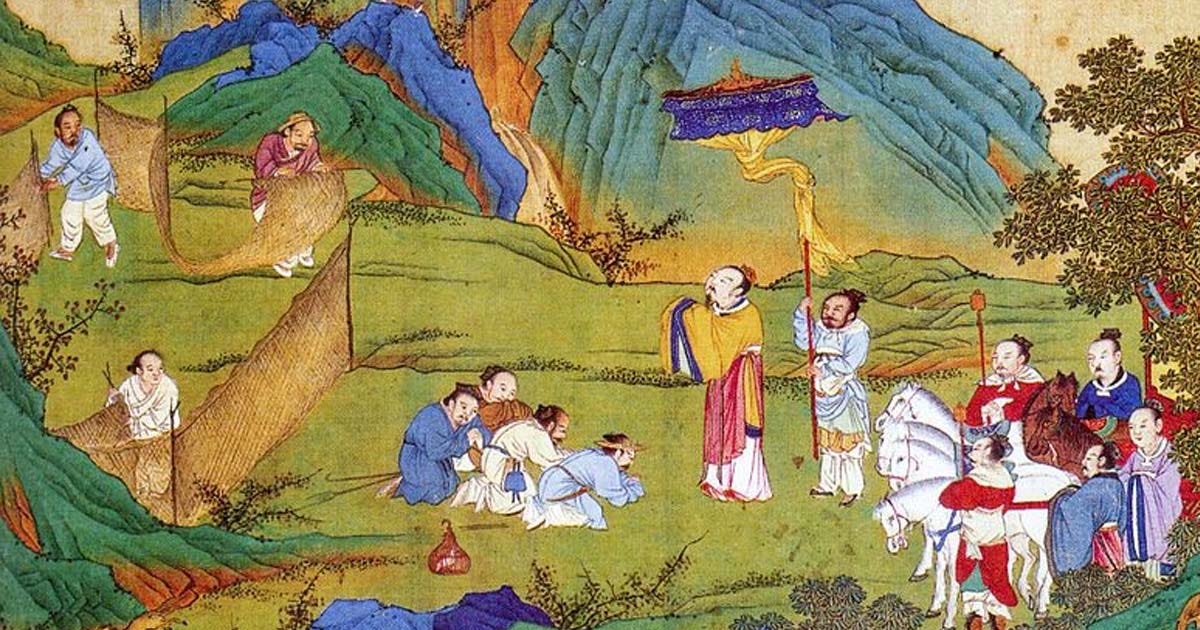

These areas were also all quite diverse in the number of populations they attracted. The Nile River valley didn’t just attract ethnic Egyptians. The Sudanese, or Nubians, were also there, as were the Meroites, the Blemmyes (Beja) and even some Semitic peoples, like the Aksumites. The Tigris and Euphrates were also remarkably diverse culturally and linguistically—a fact which Fr Paul Tarazi notes emphatically in The Rise of Scripture. The Sumerians were not Semites, but the Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians were. Yet the Sumerian language was retained and respected by the Akkadian conquerors. In addition there were Indo-European groups like Hittites and Persians in the same geographical area, and Elamites (whose isolate language is unrelated to any other on earth). And I’ve mentioned before that the Yellow and Long River Basins were home to not only various Sinitic peoples (Shang 商, Zhou 周, Qiang 羌, Rong 戎, Yi 彜), but also Austroasiatic (Yue 越), Hmong (Miao 苗), Kra-Dai (Zhuang 壯, Bouyei 布依), Turco-Mongolic (Xianbei 鮮卑), Tungusic (Donghu 東胡) and Dené-Yeniseian (Xiongnu 匈奴) peoples, and perhaps even Indo-European peoples (such as, possibly, the Rouzhi 月氏).

Still, none of this explains the divergence. Why did writing systems in West Asia and North Africa develop in a fully-phonetic direction, while Chinese developed in a phono-semantic direction?

My best guess is that the reason for this divergence ultimately had something to do with geography and relative ease of movement. The civilisations in West Asia and North Africa developed along river systems where the fertile basin was fairly narrow. In each of these cases, you can literally see from space the narrow band of fertile terrain watered by the rivers in question—a stark contrast against the surrounding desert. China is somewhat different: the riparian basins are much broader and the land is much better-watered and more fertile, even far away from the main rivers. People could spread out over land much more easily in East Asia than they could in West Asia. On the other hand, sea access to the Mediterranean was much easier and much more profitable in West Asia and North Africa, than sea access to the South China Sea in East Asia.

Different peoples were therefore forced to make use of each other’s languages, and the priestly castes in West Asia and North Africa were forced to deal with conquerors from up and down the river as well as from the ocean. It makes sense that languages would develop in a phonetic way sooner in such an environment. East Asia faced similar pressures, but they were not as immediate. Sure, you had Austroasiatic pirates and such off the coast, but they were never much more than a nuisance, particularly when compared with horse-riding pastoralist invaders from the North. The Sinitic languages of the Shang and Zhou therefore had to make some phonetic adjustments, but perhaps not as many or as quickly as the languages in the Fertile Crescent or along the Nile.

~~~

‘What, really, was the place He had dwelt till then?’

Again, I don’t really have that much of a problem with Saeki Yoshiro’s translation of this sentence. Bishop Aluoben’s continued asking of such rhetorical questions makes perfect sense. How are we to understand the dwelling-place of the Scriptural God? There is something that I wish that Saeki had done in addition. Again, this is a problem with an East Asian convert to Anglicanism interpreting what is in fact a West Asian text; I don’t have a problem with it and I understand it. However, I wish he had accurately ascribed to Bishop Aluoben the Scriptural pericope which this sentence references. It is in fact a paraphrase of the prophet Isaiah.

כּה אמר יהוה השּׁמים כּסאי והארץ הדם רגלי אי־זה בית אשׁר תּבנוּ־לי ואי־זה מקום מנוּחתי׃

Thus says the LORD: ‘Heaven is my throne and the earth is my footstool; what is the house which you would build for me, and what is the place of my rest?’ (Isa 66:1)

In articulating the futility of comprehending God with the human mind—Whose ways are not our ways, and Whose thoughts are not our thoughts (Isa 55:8)—Bishop Aluoben is making as strong a case as possible. There is no place (zaichu 在处in this case corresponding to māqôm מקום) that man can build, in which God will be content to rest (tingzhi 停止 being a reference to the Sabbath שבת rest of God, though earlier Aluoben had used xi 息 for the same function nūaḥ נוּח). It is interesting that Aluoben took this approach. Clearly, making this cross-functionality of the Semitic Tanakh accessible to the minds of Tang Dynasty speakers of Middle Chinese necessitated using not one but several near-synonyms.

The communication of West Asia with East Asia, again, took several different forms in the sixth century. But we can see here that Aluoben took his charge from Tang Taizong for translating the Scriptures into Chinese quite seriously. I am intrigued by the possibility that Bishop Aluoben may indeed have been in contact with the school of Arabic-speakers who were developing the Qur’ān and simultaneously spreading its knowledge among the Chinese by another route.