The lexicology of he 何

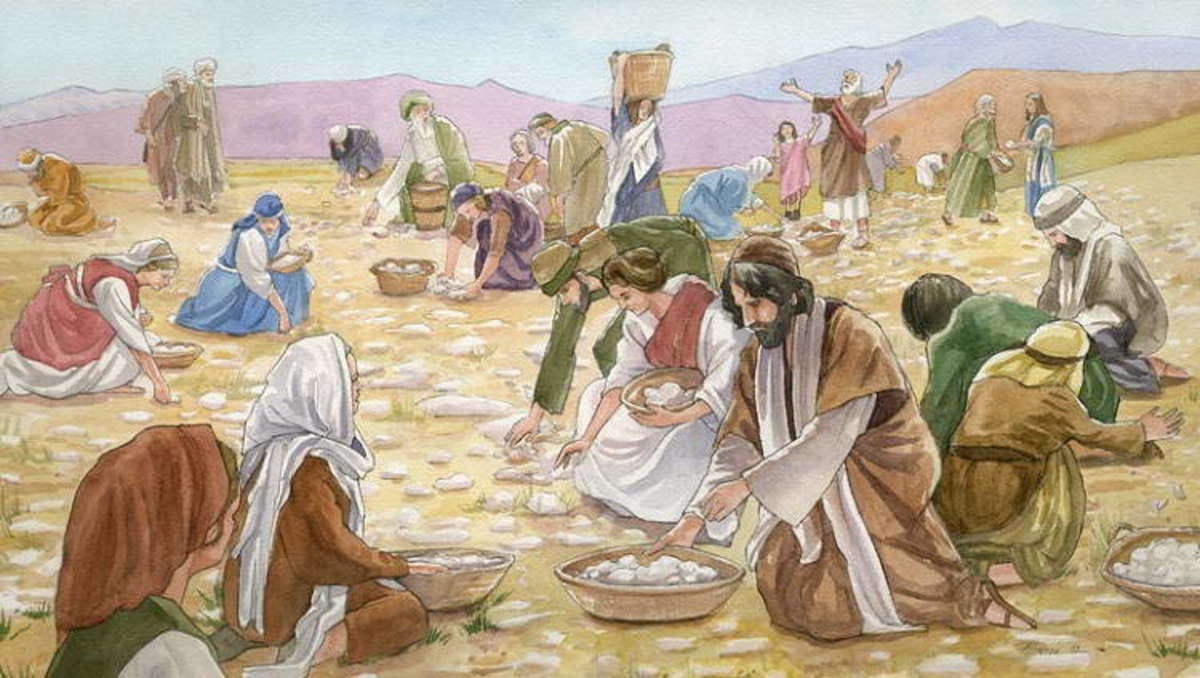

When the people of Israel saw it, they said to one another, ‘What is it?’ For they did not know what it was. (Exo 16:15)

Whenever you hear the lexeme he 何 in modern Chinese, it’s usually either in the context of a period costume drama, or it is being used ironically in an attempt by the speaker to sound ‘old-fashioned’. It’s kind of like in English, saying ‘forsooth’ or ‘zounds’ or speaking in ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ and ‘dost’. Actually: he 何 is almost exactly like the English ‘wherefore’ in that sense! ‘Wherefore’ is a perfectly valid English synonym for ‘why’, but we simply don’t say it in our day-to-day, unless we’re quoting Shakespeare, or unless we’re trying ironically to sound like Shakespeare. But in classical Chinese, he 何 was the go-to interrogative adverb and pronoun used most prominently in Zhou, Spring-and-Autumn and Warring States texts. It existed alongside others (such as qi 豈, ji 几 and xi 奚, or hu 胡, he 曷 and he 盍—see my commentary on fa 法) but it was by far and away the most common among them.

He 何 originated as a pictogram, but it is interpreted by Xu Shen in the Shuowen jiezi as a phono-semantic glyph. That is to say: it began as a single pictorial representation, in its original form, of a man (ren 人) carrying a pole-weapon called a dagger-axe (ge 戈) over his shoulder. It originally carried the function of ‘to bear, to carry a burden, to carry on one’s back’. But even by the time of the Eastern Zhou, the character had already evolved so that the person and the carried object were separate glyphic elements. The man (ren 人) is depicted to the left of a ‘mouthful’ of something or a ‘puff’ of air (ke 可). This indicates its phonetic value, which was similar to the modern English word ‘call’.

As a general interrogative adverb and pronoun, he 何 possessed the functions of ‘who’ and ‘what’, but also ‘how’, ‘why’, ‘which’ or ‘where’. In certain postclassical texts, it acquired the additional verbal function of ‘to ask, to inquire’. Again, in modern Chinese, it is not very common in everyday use, but its use in period dramas and literature is frequent enough to make it the 229th-most common character in written Chinese. The one compound where it appears frequently in modern use is renhe 任何 ‘any, whatever’. But it is used in other archaisms like ruhe 如何 ‘how’ (nowadays zenme 怎么); weihe 为何 ‘why’ (now weishenme 为什么); heshi 何时 ‘when’ (nowadays shenme shihou 什么时候 or jidian 几点); wulun ruhe 无论如何 ‘regardless, nevertheless, be that as it may’ (still used vernacularly, but nowadays suiran 虽然 in conjunction with danshi 但是, or fanzheng 反正, are more common); hezai 何在 or hefang 何方 ‘where’ (nowadays nali 哪里 or nar 哪儿); hewei 何谓 ‘what does it mean’ (nowadays shenme yisi 什么意思); and heren 何人 ‘who’ (nowadays shenme ren 什么人, or shei 谁).

The usage of he 何 is ubiquitous in the Classics. We’ve already seen it used in Odes like ‘Road Dew’ (谁谓雀无角、何以穿我屋。 ‘Who can say that the sparrow has no horn? How else could it bore through my house?’ ), ‘Grand Thunder’ (何斯违斯、莫敢或遑。 ‘How was it he went away from this, not daring to take a little rest?’) and ‘Bustard Feathers’ (不能蓺稻粱、父母何尝。 ‘We cannot plant our rice and maize; how shall our parents get food?’). But the versatility of the interrogative adverb can be seen best in an Ode like ‘Artful Words’.

彼何人斯、居河之麋。

無拳無勇、職為亂階。

既微且尰、爾勇伊何。

為猶將多、爾居徒幾何。Who are they?

They [are like men who] dwell on the banks of the river;

And they have neither strength nor courage,

While yet they rear the steps of disorder!

With legs ulcerated and swollen,

What courage can you have?

You form plans great and many,

But your followers about you are few.Book of Odes 《詩經》, Decade of Xiao Min 小旻之什, ‘Artful Words’ 巧言 6

See here how the interrogative pronoun is functioning as ‘who’, ‘what’, and also ‘few’? Legge’s translation doesn’t quite do justice to the original Chinese. The author is rhetorically asking, in something of a mocking tone, ‘but how many followers do you have?’ Although Legge’s translation preserves the general gist of what the author is trying to convey, it loses certain qualities of author voice from the original. It misses the rhetorical question, and with it the ironic ‘you-and-what-army’ tone that the original Chinese contains.

Another thing that is clear is that the versatility of this single lexeme across so many interrogative functions, mirrors the similar range of versatility enjoyed by the Semitic mâ מה or ما or ܡܐ. Now, the connexion between mâ מה / ما / ܡܐ and he 何 allows me to make this same point with regard to translation of the Tanakh, a fortiori.

There is a point in the Book of Exodus, when the Hebrews are in the wilderness, grumbling about how hungry they are, and complaining that Moses had led them into the desert to die. God sends quails around the face of the wilderness in the evening, and after them the dew in the morning, and after the dew evaporates, what is left is something that the Hebrews did not know what it was (mâ-hû’ מה-הוא), and so they called it, quite literally, ‘What?’ (mān מן, Exo 16:15). Yet in all the English translations I see, they switch to calling it ‘manna’ (Exo 16:31), even though in the Hebrew they clearly keep calling it ‘what?’, and the text literally explains why they call it that.

One is tempted to go full Samuel Jackson on the English translators of the Tanakh, holding them at gunpoint: ‘“Manna” ain’t no bread I ever heard of. Say “manna” again, I dare you…’ Hebrew: do you speak it?

This is a fairly good object lesson in a point that Fr Paul Tarazi makes with some frequency. When you are reading an English Bible, you are not reading the Hebrew Tanakh. When you are reading the English translation of Exodus, you do not get the humour of Moses commanding the Levites to take a great big jar of ‘what?’ (min מן) and preserve it, so that the descendants of the Hebrews might be able to see ‘what?’ (mān מן) they were given to eat in the desert. Moses, and thus the text itself, mocks the faithlessness of the Hebrews. It mocks their gormless dumbstruck reaction to finding food on the ground in the desert—from the same God who saved them from slavery in Egypt and drowning in the sea. The wordplay, and even the basic lexical values of the vocabulary, do not survive translation. English hearers interpret ‘manna’ just as meaningless sounds. It doesn’t function in our language. We hear those sounds ignorantly, the same way we hear the Hawaiian ‘mana’. On the other hand, though, I hear the Hawaiians got some tasty burgers…

Thus Moses’s command to the Levites takes on, in English, a tone of empty piety. It becomes a gesture of self-aggrandisement, grounds for the historical establishment of a merely-human ritual. We hear this in English and imagine ourselves to be good little Hebrews making our way piously through the desert to the magical land of promise. But any speaker of a Semitic language would realise that Moses is dunking on the Hebrews. They are under instruction in this passage, as God’s newly-hired servants, and they are, bluntly, not shaping up.

~~~

‘Who can discourse concerning the whereabouts of the Lord of Heaven previous to His revelation?’

This is PY Saeki’s translation of the subsequent sentence in the Xuting Mishisuo jing. As translations go… it’s actually not bad. I particularly like the fact that Saeki preserved the implied rhetorical question, and that he managed to capture the dual functions and wordplay of xian 显 with his ‘previous to His revelation’ rendering. Even so, what the text is asking is: after ’Elohim was there, who would know where He was, if He had not revealed Himself? The text is talking both about God’s reality, and also His inexistence except from the text.

Bishop Aluoben had a difficult task before him. He had to convince the Chinese of the necessity of following a revealed text, but this happened after the arrival and propagation in China of a Hellenistic form of Buddhism influenced by Alexander’s conquests. He therefore had to navigate a linguistic sphere with its own neglected prophetic tradition—with which, through his reading of the Classics, Bishop Aluoben would have had to have been partially familiar. But in doing so, he was forced to adopt the usages of both popular Daoism and of his (philosophically-minded) Buddhist competitors. Thus, when he opens the Xuting Mishisuo jing, he is largely speaking in rhetorical questions meant to evoke a negative response, similar to the Ode composer who wrote the ‘Artful Words’.

Whether or not Aluoben succeeded in his task is lost to us. The initial community of Syriac Christians in China was expelled toward the end of the Tang Dynasty; a subsequent one came to take its place in the Yuan Dynasty before that too was expelled in the Ming. Orthodox Christians only came back to China during the Qing Dynasty, in the 18th century—and they were Russian, not Syriac. And to a certain extent, Aluoben’s worldly success in the 7th century AD, in building his community, is irrelevant to the ultimate question. We have his words in Chinese: the words which Emperor Tang Taizong permitted him to write. The work that is left to us—Chinese scholars, Semitologists and specialists in Asian languages and history all alike—is lexicographical.